Born by accident due to a rushed foreign policy, revived after having collapsed, yet not having a clear direction. These are the broadest brushstrokes possible to describe the ongoing Afghan peace talks between the US and Taliban. Six rounds of such talks have been held in Doha, Qatar since October 2018 led by Zalmay Khalilzad, the US Special Representative for Afghanistan.

The talks are aimed at putting an end to the 18 years long war in Afghanistan. Last month, the Afghan government led by Ashraf Ghani parallelly held a loya jirga (grand assembly) of some 3200 participants. This was after an earlier meeting between Taliban and Afghan political figures got canceled due to disagreement over the participants and the size of the delegation. Amidst all this, presidential elections are scheduled to be held in September this year after getting postponed twice.

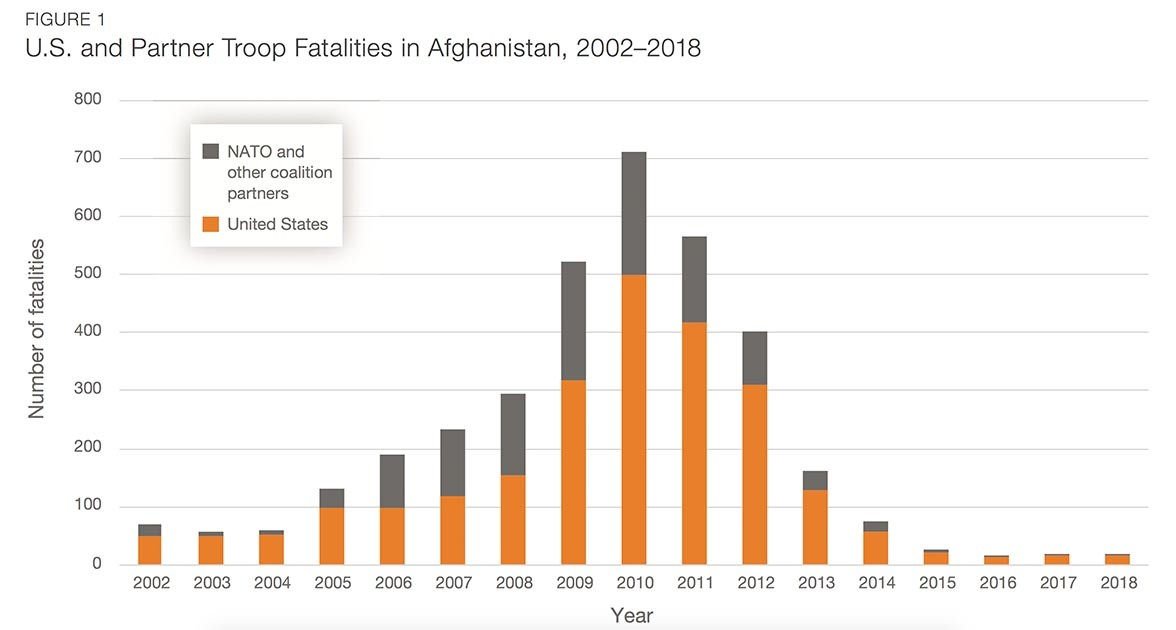

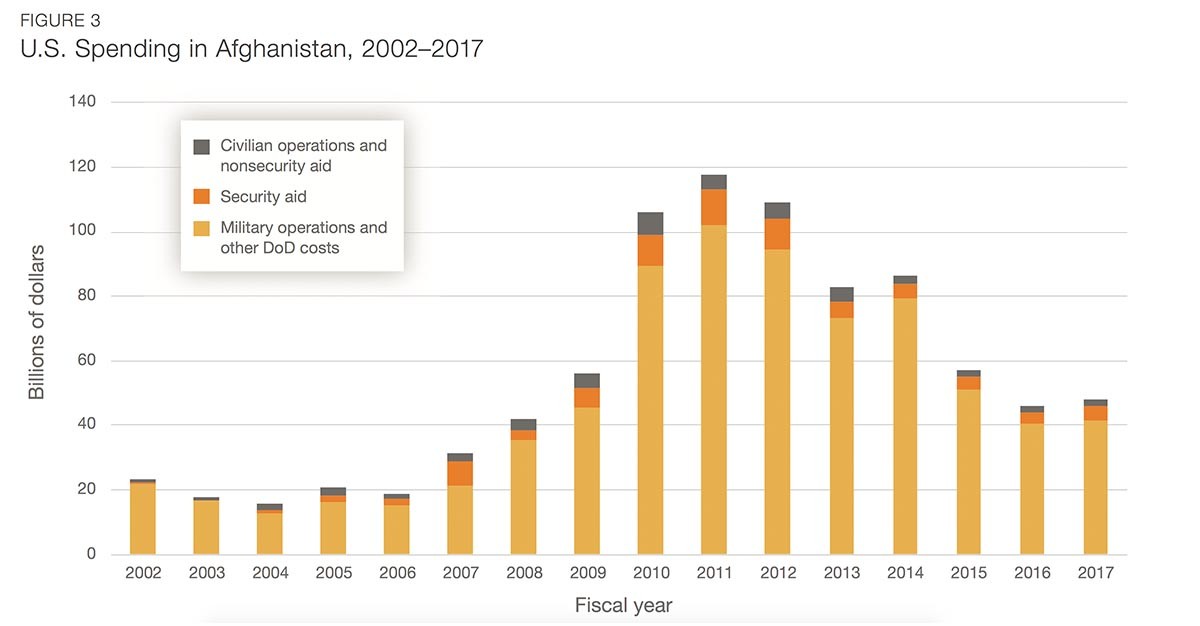

Earlier, Taliban had refused to talk to the Afghan government calling it a US “puppet”. Worryingly, the US has had no problems with the exclusion of the Afghan government, civic groups and other stakeholders. The peace talks are driven by President Trump’s promise to extricate the US from costly global wars. Equally, these talks could be driven by a war-fatigued world power with no desire to foot the bill of global conflicts. Till date, the US war in Afghanistan has resulted in more than 2300 military deaths and a whopping cost of more than 1 trillion US Dollars.

Taliban were the very reason why US invaded Afghanistan in 2001 after they refused to hand over Osama Bin Laden. Taliban may have possibly earned their leverage through control of a sizeable chunk of Afghan territory.

Pakistan has played a crucial role in organizing these peace talks despite earlier US accusations of Pakistan’s support of the Taliban. In a sign of desperation for the US, President Donald Trump wrote a letter to Prime Minister Imran Khan last year in which he sought Pakistan’s support in securing a negotiated settlement to end the war in Afghanistan.

Some Burning Questions

What is the likelihood that these peace talks will lead Afghanistan to a stable future? Or, in a repeat of history, are we about to see another scramble for power by regional players as the tectonic plates shift underneath one the most volatile regions in the world? What is the current posture of regional countries towards Afghanistan? In a break from history, will they will view Afghanistan differently this time – possibly as a potential hub for economic cooperation as opposed to a strategic battleground?

Flaws in US Policy

Let us first unravel the flaws in US policy which got us here. Two aspects, in particular, stand out. First, the only two negotiating parties are the US and Taliban. Besides the Afghan government, conveniently ignored are other Afghan ethnic groups, factions and civic society.

Second, till now, the talks have focused on only two issues: US pledge to withdraw troops from Afghanistan within 18 months of a peace agreement in exchange for the Taliban’s vow not to allow Afghan territory to be used against US interests. Till date, there is no indication of any timeline of US withdrawal or how the Taliban will ensure that Afghan territory is not used against US interests (something seriously doubtful).

Read more: US-Afghan peace talks: Long way to go before ‘drafted agreement’

Reportedly, a draft framework agreement was reached between the US and Taliban in January this year. This framework agreement, besides incorporating the two main issues (US withdrawal, and Taliban not allowing Afghan territory to be used against US interests), will form part of a broader pact that, amongst other things, will involve a political settlement between the Taliban and the Afghan government.

A tall order indeed, considering that in the midst of the peace talks Taliban have launched their yearly spring offensive. International media has been abuzz with criticism of the US choice of negotiating with the Taliban. Clearly, this criticism has merit.

Taliban were the very reason why US invaded Afghanistan in 2001 after they refused to hand over Osama Bin Laden. Taliban may have possibly earned their leverage through control of a sizeable chunk of Afghan territory. Regardless, the US choice has sent a dangerous message to the world that it can strike a deal with non-state actors if its interests are at stake.

Read More: Afghan peace talks: Deadlock in Doha?

Worryingly, in a repeat of history, the US has overlooked the complex Afghan religio-political, social and cultural matrix. This omission was exploited in the post-Soviet era (1989) by regional powers (India, Pakistan and Iran) that took sides in a dangerous power play that saw the Taliban, Northern Alliance and regional factions used for strategic pursuits.

The US’s decision to merely talk to the Taliban (who are Pashtuns and comprise around 42% of the Afghan population) is an affront to the remaining ethnic groups who will inevitably feel being left out.

According to media, right before the last round of peace talks in Doha, the Taliban’s Chief Negotiator Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanekzai reassuringly exclaimed, “God has helped us defeat two superpowers in the last century. The third superpower that we are currently confronted with is also on the verge of defeat”. If history is any guide, Mr. Stanekzai’s statement is correct.

The Complex Afghan Demographics

The areas known as present-day Afghanistan and inhabited by the Pushtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks, and Turcomans, was called Ariana in ancient times and Khurasan in the medieval times. Traditionally, Afghans are people who honor the dictates of religion, custom, culture, tribe, clan, village, and family.

Ahmed Shah Durrani became the first king of modern day Afghanistan in 1747. It was during his reign that the need to balance the interests of different ethnic groups came to the forefront. He had to mend the fault lines between the warring Pashtun tribes (the dominant ethnic group) as well as bring others such as the Farsi- speaking Tajiks, Shia Hazaras, Turkish speaking Uzbeks and Turkomans under one umbrella. Ahmed Shah successfully managed to coalesce these groups which gave rise to the first ever Afghan common consciousness.

Read more: Apparent breakthrough in Afghan peace talks

Historically, there were possibly two ways in which Afghanistan could be governed: either coalesced by a man like Ahmed Shah Durrani or ruled through force by a ruler such as Amir Abdul Rehman (1880-1901) or the likes of Mullah Omar who galvanized the rural, orthodox religious power base.

Religion has always been center stage in the Afghan’s life. Anyone who tried to replace Allah’s Law with the king’s law was fiercely resisted. To this fell victim King Amanullah (1919- 1929) who tried to push through liberal Western reforms in Afghanistan by showing no regard for the centuries-old traditions, customs, and religious feelings. The also became the fate of the leftist rulers who came after King Daoud (toppled in 1978).

Present-Day Afghanistan is a result of the same rich cultural history which never accepted foreign occupation. The US’s decision to merely talk to the Taliban (who are Pashtuns and comprise around 42% of the Afghan population) is an affront to the remaining ethnic groups who will inevitably feel being left out. Due to this policy flaw, Afghanistan’s’ future map of “political control” may not resemble its ethnic map.

India, on the other hand, saw an unprecedented opportunity in post-911 Afghanistan. India has historically claimed Pakistan’s support of Taliban for proxy war at the eastern front.

The Great Game Across the Afghan Chessboard

Historically, on three occasions, Afghanistan has been the battleground for the great game played out between world powers. First, in the 19th and 20th centuries, there was a tussle between the 19th Century British Empire that covered 23 percent of the world land mass and the fast-expanding Russian Empire that stretched from the Baltic/Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean. Squeezed between the two world powers was Afghanistan.

Russia’s ambitions in Afghanistan lay in its desire to access warm waters as its sea routes through Bosporus, St. Petersburg and the Arctic Ocean were clogged for about 9 months in a year. From the British point of view, there was real concern about Russia’s intentions and capabilities and about the threat that its expansion posed to the defenses of India. It was also feared that Russia’s rise would disrupt lucrative British trade with China.

Great Britain attacked Afghanistan twice to bring it under its complete control in 1839 and 1878 but could not succeed. Over a period of time, both Russia and Great Britain settled on making Afghanistan a buffer state between the two. This led to Afghanistan and British Raj agreeing to finalize the contours of the boundary between Afghanistan and British India, known as the Durand Line in 1893.

Read more: Peace in Afghanistan in interest of Pakistan, Iran: PM Imran Khan

The second great game commenced after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 which set in motion the Cold War between the US and USSR. The US armed the Mujahideen in Afghanistan to resist the Soviets through support by Pakistan. This eventually resulted in the Soviets’ defeat and exit from Afghanistan in 1989.

The Mujahideen came into power in Afghanistan in 1992 but the factions that comprised the Mujahideen would start fighting one another. In the ensuing struggle, India, Iran and Pakistan opted to take sides. While India sided with Burhanuddin Rabbani’s Jamat-i-Islami and Iran with Abdul Ali Mazari’s Hizb-e-Wahdat, Pakistan supported Gulbadin Hikmatyar’s Hizb-e-Islami. It was in response to these alliances that a group of madrassa students known as the Taliban “emerged in Kandahar to restore order”.

It was not until 1994 that the Taliban emerged on the scene in Afghanistan as a potent force. Taliban would go on to conquer Kabul in 1996 and establish their rule in Afghanistan which continued until their ouster from power in 2001. The US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 was the third time that world powers would indulge in another power play in Afghanistan.

Post 911 Geo-strategic Posturing

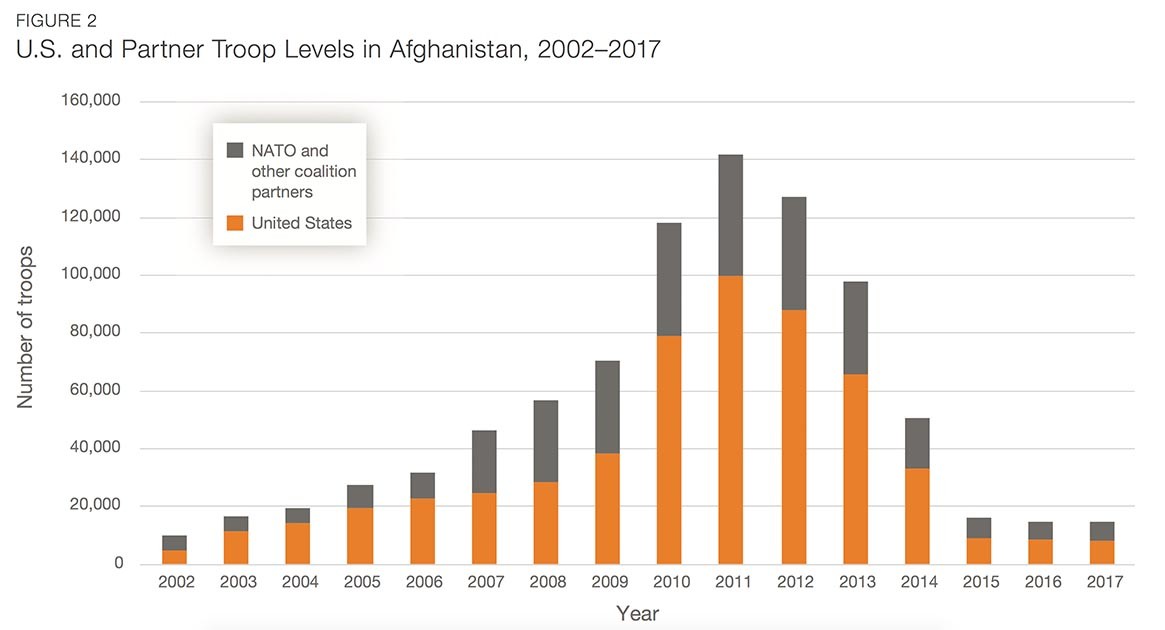

In the early days of the US invasion, US policy was solely focused on eradicating Taliban and Al Qaeda from Afghanistan. Over time, there was wide-ranging multilateral cooperation between the US and NATO countries for nation-building in Afghanistan.

This fear came true after the fall of Kunduz in 2015, a city closely situated to Tajikistan, which has remained under Russian influence. This left Russia was no option but to engage the Taliban to safeguard its geopolitical rear.

US military gains in Afghanistan occurred because of active support by Pakistan. This was a war that Pakistan reluctantly joined due to limited choices. Pakistan rarely received praise for its efforts and mostly criticism for not doing enough. Pakistan also faced allegations of continuing with its “strategic depth” policy of supporting the Taliban. While at times the US criticized Pakistan for not doing enough, at other times, it chose to look the other way.

Over time, Pakistan developed its own set of grievances against the US: the staggering human cost of the conflict (thousands of military and civilian casualties), and the Salala and the Raymond Davis incidents (2013), all of which collectively drove a deep wedge between the US and Pakistan.

The last nail in the coffin for Pakistan was the US decision last year to suspend the entire security assistance to Pakistan or reimburse Pakistan for the expenses incurred towards the Afghan war. India, on the other hand, saw an unprecedented opportunity in post-911 Afghanistan. India has historically claimed Pakistan’s support of the Taliban for proxy war at the eastern front.

Taking advantage of the geopolitical tilt after the 911 attacks, India sided with the US and went on to take an active part in nation building in Afghanistan which saw Indian consulates open up in major cities. Pakistan eyed those developments with suspicion and alleged that this was India’s subterfuge for acting against Pakistan’s interests in the region. To its credit, India was able to maintain a close strategic and economic relationship with Afghanistan throughout.

Two world powers, one with a bruised ego (Russia) and the other an emerging powerhouse (China) cautiously watched the developments from the sidelines. Back then, Afghanistan was not central to China’s security paradigm. For Russia, on the other hand, with its ego hurt but ambitions intact, there were scores to settle with the US.

Read more: US-Taliban talks: Grand Jirga to predict the future of Afghanistan

Present Day Geo-strategic Posturing

U.S.

Much has changed since the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. US policy which started off with altruistic ideals to introduce rule of law, democracy and stability in Afghanistan has shifted to one of hedging towards Taliban to prepare for the eventuality of a hostile takeover of Afghanistan by them. Shades of this policy are also visible in other countries’ geo-strategic policies which too have been shaped by certain anticipated threats and challenges.

Russia

Over the years, in a resounding reversal, Russia has clawed its way back into the Afghan theatre. Starting from 2018 onwards, Russia’s public posture has been to view the Taliban as the go-to-guys. Russia initiated what came to be known as the Moscow Process – involving, Iran, Pakistan and China – for reaching a political settlement in Afghanistan. The notable omission in the November 2018 round of talks was the Afghan government.

Some possible reasons behind Russia charting its own course in Afghanistan are Russia’s concerns about the US repeating the same mistakes it made during the Soviet occupation and that a US exit will unleash forces that would threaten its interests in the region. This fear came true after the fall of Kunduz in 2015, a city closely situated to Tajikistan, which has remained under Russian influence.

This left Russia was no option but to engage the Taliban to safeguard its geopolitical rear. Moreover, Russia has always had inhibitions about the US establishing a permanent base in its backyard. This is a common concern shared by Iran, a close Russian ally, which due to its bitter rivalry with the US has been deeply concerned about a permanent US presence in its geographic north-east.

This beguiling narrative would echo across Western policy circles even during US calls on Pakistan to facilitate talks with the Taliban. In its riposte, Pakistan would argue that claims of Pakistan’s leverage over the Taliban are exaggerated.

In what would appear to be common ground between the US and Russia on Afghanistan, in March this year, Russian Foreign Minister expressed support for US-Russian cooperation. Only time will tell if such statements are a concrete manifestation of US-Russia entente on Afghanistan. Despite Russia’s increased interest in Afghanistan, its footprint in Afghanistan is expected to be minimal due to its diminishing global economic clout.

China

China’s rise in the Afghan theatre is a lesson in astute statecraft. In the early days of the US occupation, China chose to stay on the sidelines. Lately, however, China has been emboldened by US stumbles and waning interest in Afghanistan and has gradually repositioned itself in Afghanistan.

Unlike Russia, whose geo-strategic pursuits are defined primarily by security, China’s policy towards Afghanistan has both a security and economic dimension. In fact, it is China’s economic interests driven by its behemoth BRI project that has prompted China to view Afghanistan as a vital cog of its BRI wheel.

On the security front, like Russia, China too fears that a hurried US exit from Afghanistan would unleash threats in its direction such as the ethnic Uighur separatists. China has therefore intensified security on its border and engaged in joint patrols with Afghan forces as well as entered a multilateral security framework in collaboration with Afghanistan, Pakistan and Tajikistan.

Read more: No one more desperate for peace in Afghanistan than Pakistan

On the economic front, China is the largest foreign investor in Afghanistan and is reportedly planning to increase its investments. In 2017, Beijing convened a trilateral dialogue with Pakistan and Afghanistan to discuss extending BRI to Afghanistan. China’s economic activity in Afghanistan is set to grow in the coming years provided that the security equation remains favorable to China.

India

India views a Taliban takeover of Afghanistan as a direct threat to its almost two decades long footprint in Afghanistan which it established through a close military and economic alliance with the Afghan governments. In response to China’s 60 billion CPEC project in Pakistan which can enhance China and Pakistan’s influence in the region, India set up the parallel Chahbahar port in collaboration with Iran. However, the Chahbahar port pales in comparison to the CPEC project whose potential to connect regional trade hubs remains unmatched.

In another major setback for India, the US has recently reimposed sanctions on trading in Iranian oil. However, the biggest threat to India’s ambitions is if the US and Iran go to war, something likely in light of the recent sabre-rattling by both sides. Faced with the fast-moving events in the region, India can be expected to further strengthen its alliance with US.

Pakistan

Since the US announcement of troops withdrawal from Afghanistan, once again Pakistan has been thrust in the limelight. Traditionally, Pakistan has faced an unending chorus of allegations of supporting Taliban and siding with them in a double game against US interests. This beguiling narrative would echo across Western policy circles even during US calls on Pakistan to facilitate talks with the Taliban. In its riposte, Pakistan would argue that claims of Pakistan’s leverage over the Taliban are exaggerated.

The Afghanistan issue should be debated at the UNSC as a threat to international peace and security and be followed by a UN sponsored peace initiative which takes on board all segments of Afghan society.

Regardless, Pakistan has taken commendable steps to exonerate itself from these allegations. Not only has Pakistan played a key role in facilitating US-Taliban talks, Pakistan’s policy has also been one of neutrality. Despite the Taliban’s recent aggressive posture in Afghanistan, Pakistan has gone so far as to make the official statement that it will not be a party to any internal conflict in Afghanistan and that it fully supports the peace process including the intra-Afghan dialogue. Through a positive role in the Afghan peace talks, Pakistan is also keen to mend fences with the US with whom Pakistan’s recent relationship has been rocky and full of mutual distrust.

Afghanistan as the Eurasian Bridge of Economic Opportunity

If history is any guide, the road to Kabul has never been paved with good intentions. However, the rushed manner in which the US has sought the exit can leave a dangerous power vacuum in Afghanistan with devastating consequences for the region.

After the US decision, the geo-strategic choices faced by the regional countries (India, Pakistan, Iran, Russia and China, no less) are indeed real. More than anything, these choices are suggestive of the actual or perceived threats foreseen by all countries. Every country has its own concerns, grounded in a perception oriented posture, due to which it has engaged in a zero-sum game in which it visualizes itself as the only winner. It is this perception that has in the past triggered the fight for the entire prize instead of settling for something less which can be mutually shared by all.

Read more: U.S-Pak high-level delegation met to discuss the Afghan peace process

This perception, which is not unique to Afghanistan, is the driver behind conflicts around the world. It is in somehow overcoming this perception that conflict-ridden countries such as Afghanistan can see some hope of resolution. How is this possible? First is the need to take the sting out of the geo-strategic compulsions faced by countries towards Afghanistan. One possible way this can happen is if all countries in the region view Afghanistan as an opportunity instead of a threat. With no clear winners in Afghanistan in history, all countries must learn that giving prize sharing precedence over walking away with no prize is the only way forward.

This will, however, require viewing Afghanistan with a fresh set of eyes, as an untapped reservoir of equal economic opportunity for the entire region. In this respect, the role of China and Russia is perhaps more crucial than it has ever been in history. However, before the economic opportunity shines brightly before the world, China and Russia will need to use their global heft and somehow arrest Afghanistan’s decline.

For this, China and Russia can use their clout as the two permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). The UN Charter has entrusted the UNSC with maintaining global peace and security. The Afghanistan issue should be debated at the UNSC as a threat to international peace and security and be followed by a UN-sponsored peace initiative which takes on board all segments of Afghan society.

In order for the above to happen, BRI’s expansion in Afghanistan should not be seen as a threat by other regional countries, especially India. Critics have called China’s BRI the vehicle for expanding its geo-strategic footprint in the region.

The possible roadblocks to this are: China and Russia agreeing on the same thing in the same sense vis a vis Afghanistan; US opposition if it sees the UN route as a threat to the going peace talks and; working around previous UNSC resolutions that designated Taliban as sponsors of terrorism. Another significant challenge would be getting the Taliban to relinquish their role as the power brokers for Afghanistan – something they cannot be expected to give up easily.

China and Russia have common security concerns in Afghanistan. Both see threats emanating from Afghanistan as detrimental to their interests. Both agree that a hedge against those threats is through peace and stability in Afghanistan. Both, however, like the US, have made the fundamental policy error of treating the Taliban as the legitimate power broker for Afghanistan. This will have to change. Both Russia and China will have to put their weight behind the UN-sponsored peace initiative in which all segments of Afghan society are represented.

US opposition to the UN-mandated peace initiative can be avoided by incorporating the agreed points of the US-Taliban peace talks in such UN initiative. At the same time, however, the UN initiative must avoid conferring on the Taliban any role as the sole or exclusive power brokers for Afghanistan.

More importantly, the UN initiative can also dilute the undue leverage that the Taliban have acquired through the use of force. The world lost a major opportunity when peace talks with Taliban contained an incentive (withdrawal of US troops) but no cost (e.g. making Taliban’s acceptance in the international mainstream contingent on their giving up violent methods). Belatedly, the UN peace initiative can do some amends by making removal of earlier UN sanctions on Taliban contingent on their demonstrated ability to work with all Afghan stakeholders.

Read more: Trilateral summit between Afghanistan US and Pakistan

If a UN-sponsored initiative with China and Russia at the helm is rolled out sooner rather than later, India’s concerns about the Taliban can also be addressed under such a framework. Russia, due to its historic ties with India, can play a major role in pacifying India’s legitimate concerns in Afghanistan and convince it to come on board.

A sword hanging overhead is the current US-Iran animosity tethering on the edge of war. Even if the US is keen to exit the Afghan theatre, it may very well end up opening a new war front with Iran. At the sake of sounding utopian, perhaps it is again China and Russia that can play a positive role in tempering down aggression on both sides. If the ongoing power tussle can somehow end, there are immense opportunities lying in store for Afghanistan and the region.

China’s BRI is an example of a mega project that can shape Afghanistan as an economic powerhouse. Afghanistan is helped by its geography. It is the Eurasian bridgehead connecting the east to the west and Central Asia in the north to warm waters of the Indian Ocean through Iran and Pakistan. Afghanistan also offers the shortest route between Central Asia and South Asia, as well as between China and the Middle East, while also serving as a gateway to the Arabian Sea.

While no mega projects of this scope are without their inherent geo-strategic drivers, China and Pakistan will have to allay genuine fears and concerns of India and Iran, two countries that can be the spoilers unless they are taken onboard.

Another promise Afghanistan holds is that of providing Russia the shortest access to warm waters. Historically, Russia’s geostrategic posture towards Afghanistan has been shaped by this survival instinct. A repeat of history may be avoided if the region forges a common consciousness, something akin to the European Union, in which all regional countries have access to trade hubs transiting through Afghanistan. Once again, BRI can be the crucial gateway that can make this happen.

Economic promises cannot be fulfilled unless there is an environment of lasting peace and security. BRI’s “cross-continental connectively” can also soften the edges of conflict and bitter rivalries in Afghanistan. Economic betterment can help Afghanistan in finding the missing link: peace and stability. Afghanistan’s torn social fabric can hopefully also heal when all segments of society are allowed a share in the economic pie.

Read more: US envoy seeks peace deal in Taliban talks before Afghan elections

In order for the above to happen, BRI’s expansion in Afghanistan should not be seen as a threat by other regional countries, especially India. Critics have called China’s BRI the vehicle for expanding its geo-strategic footprint in the region. While no mega projects of this scope are without their inherent geo-strategic drivers, China and Pakistan will have to allay genuine fears and concerns of India and Iran, two countries that can be the spoilers unless they are taken on board.

The road to Kabul has never been paved with good intentions. But perhaps never before in history has Afghanistan been so central to regional peace and stability as it is today. The regional powers will have to come to terms with this reality sooner rather than later. Afghanistan’s survival this time is linked with the future of the region. This time around, the world perhaps has no choice but to fight for Afghanistan.

Hassan Aslam Shad is the head of corporate and international practice of a leading law firm of Oman. He is a graduate of Harvard Law School, U.S.A. with a focus in international law. Over the years, Hassan has written extensively on topics of law, including public & private international law and international relations. Hassan has the distinctive honor of being the first person from Pakistan to intern at the Office of the President of the International Criminal Court, The Hague. He has also represented Pakistan at the prestigious Jean Pictet international law moot court competition. He can be reached at veritas@post.harvard.edu.