Living for more than 3 years in the heart of Dubai, I experienced the city as it presents itself on TV and newspaper advertisements – the glitz, the plethora of tourists, the extravagant shops, high-rise apartments, huge boulevards, assorted eateries, and affluent supercars. I witnessed an elitist lifestyle where the well-off residents and tourists seemed euphoric – Dubai acted just as advertised.

It was only when I started taking cabs back and forth from my residence to my academic institution, University of Wollongong, that I first heard the narrative of the ‘common man’. Most cabbies in Dubai are Pakistani and being from the same nation, I usually engaged in meaningful conversations with them regarding the city. Their narrative acquainted me to an astonishingly dissimilar city, which had strict rules, more work, and little freedom.

The GCC states and their cities have many similarities: Firstly, they are rentier-based economies, which rely heavily on immigrants for their overall development.

I became so enthralled with the cabbies’ experiences, that I did my Masters’ dissertation on them. Through their eyes and the magic of primary and secondary research, I became cognizant of a Dubai and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries that usually elude the perceptions of many.

Doha, Manama, Kuwait City, and Dubai are considered GCC cosmopolitans – people from all over the world live in seeming harmony, a surfeit of diverse ethnic restaurants is available, and surprisingly a few churches and temples besides the numerous mosques are also present. Paradoxically, however, only when one delves deeper into ground realities, is it discerned that certain anti-cosmopolitan tendencies are at play in these cities.

The Paradox of the GCC Promise

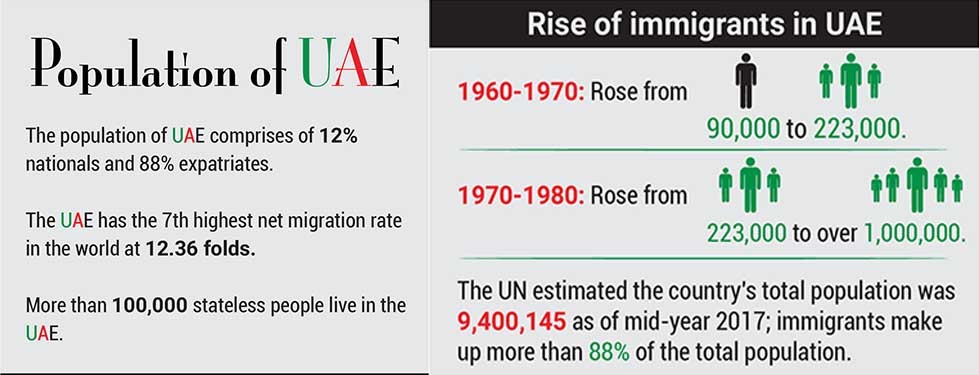

The UAE is a peculiar state due to its demographic landscape consisting of more foreign nationals than its local population. Although this idiosyncrasy might be alien in most parts of the world, it is a recurring characteristic for most of the countries in the GCC. Saudi Arabia and Oman are the only exceptions to this rule with non-nationals in the UAE, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar comprising 88.5%, 69.2%, 52% and 85.7% of the total population respectively.

GCC cosmopolitans are considered beacons of progress and centres of innovation in an otherwise fractured the Middle East. The GCC states and their cities have many similarities: Firstly, they are rentier-based economies, which rely heavily on immigrants for their overall development. Secondly, they are all monarchies and the ruler has absolute power for the most part.

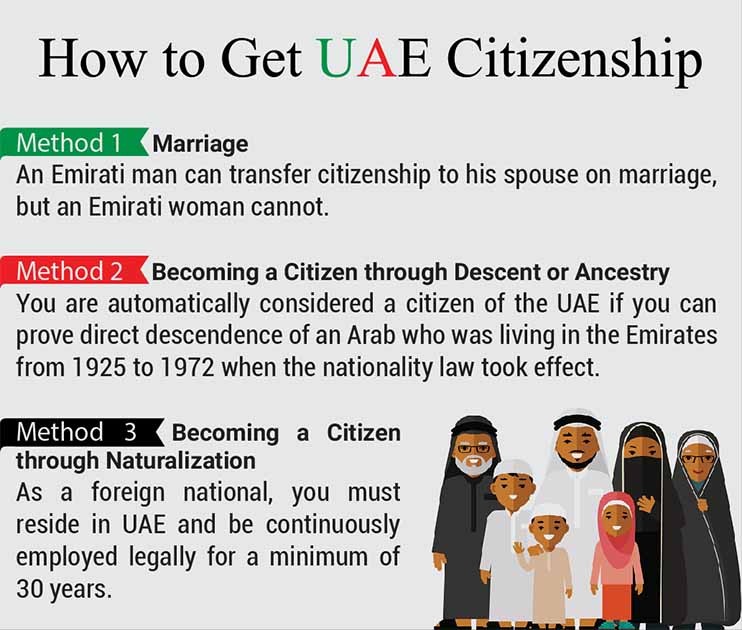

Thirdly, with slight variations, they all have exceptionally restrictive and deterring citizenship or naturalization policies. The latter inveterate policy leads to the creation of an emphasized dichotomy among the population which dominates the landscape i.e. locals versus expatriates. In fact, there are even subdivisions among the locals (i.e. full citizens, semi-citizens, and Biduns – stateless people) and between the expats (i.e. upper-class, middle-class, and lower-class).

Within this atmosphere, national identity, citizenship type, and social class of locals and expats become increasingly underscored. Citizenship is the tension between inclusion and exclusion of individuals. Dr. Gwenn Okruhlik asserts that citizenship is multidimensional – for those included, it offers rights, membership and empowerment while the excluded can be subjected to alienation, marginality, and relegation.

Zahra Babar remarks that benefits for Qatari nationals are quite immense which lead to citizenship being restricted for non-nationals due to economic burdens and also due to expats forming the bulk of Qatar’s population. The citizenship rights that are afforded to GCC countries’ respective citizens generally include but are not limited to free healthcare, free education, subsidized loans, free land, and also preferential treatment in public sector jobs.

Read more: Nationality, Citizenship & Class in UAE & GCC: Beyond the glitzy…

In the Gulf and other rentier states, political freedom is sacrificed for these vast citizenship rights and privileges; the government does not generally impose taxation upon the public but relies on its own independent source of revenue (usually fossil fuels) to fund development and citizen benefits. The rulers distribute money to form a stable and unified state and buy the political approval of the locals.

The foreigners (at least most of them) are exempt from such benefits and in so their ‘otherness’ is highlighted Dr. Natalie Koch highlights that Gulf nationals are part of an elite group due to the magnanimity of the state vis-à-vis the benefits they receive. Thus, the Gulf monarchies work counterintuitively to the standard set by Western democracies.

The latter countries not only create sustainable citizenship benefits for their own citizenry but also create an assimilatory environment by producing relatively lenient naturalization/citizenship policies for immigrants. In the GCC cities, conversely, there is a xenophobic mentality that has been advanced by the monarchs, to reinforce a national identity among the locals at the expense of non-citizens.

Nadia Eldemerdash highlights that nationalist narratives in Kuwait and the Gulf have depicted stateless Biduns, the most disenfranchised people in the Gulf, and foreigners as a threat to local populous which has fashioned a climate of “isolation and exclusion” for both groups. What is incredulous is that Biduns are Arab’s themselves but have been relegated to the bottom of the social hierarchy all because they did not register as citizens when the Gulf States were first establishing.

Paradoxically, however, only when one delves deeper into ground realities, is it discerned that certain anti-cosmopolitan tendencies are at play in these cities.

In Kuwait, the Biduns cannot access healthcare, education, or apply for a job and can even be deported. Nadia also remarks that the alienation of the Biduns and foreigners in the Gulf is exercised through the mechanics of citizenship. Due to their enormous numbers; expats and Biduns are seen as threats that could erode away the national culture, heritage, and lifestyle of the locals.

Dr. Koch asserts that, although, there is anxiety among locals over the immense foreigners present in their countries, they are nonetheless positioned well to benefit from incoming migrants. After the Biduns, the lower-class expats are the most marginalized community in the Gulf. The discriminatory behaviour of GCC states leads to many problems for migrants, more so for the lower-class groups i.e. cabbies, construction workers, waiters, and maids, etcetera.

Dr. Okruhlik mentions that the states institutionalize and codify inequality, segregation, and exploitation of labor. She continues, that these problems are exacerbated for unskilled workers who are dealt with intimidation and even violence – they have substandard healthcare and housing, work exceptionally long hours, and have vastly restricted mobility.

Read more: Saudi Arabia grants citizenship to robot “Sophia”

These unskilled workers, mostly from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Philippines, etcetera, also get their passports confiscated on arrival to a GCC country to ensure subservience to their employers. With regards to the Pakistani cabbies I interviewed, they were stuck in a job where they drove 12 hours every day, without any weekends off or other holidays.

One driver stated, “My shift starts at 3 am and ends at 4 pm. If we take a day off without a medical reason the [company] deducts 200 Dirhams.” The individual taxi companies also control when a driver can take a vacation (usually between a year and year-and-a-half of work). One driver informed me, “If there is a lot of work they can ask us to stay in Dubai for 2 years or even 4 years – that’s up to them.”

GCC Demand for Labor

As mentioned earlier, the expats’ numbers dominate the GCC landscape, especially in the UAE. Even before the 1950s when the 7 Emirates were the Trucial States (under British rule), migrants poured in from Arab countries, Europe, and South Asia (mainly Pakistan and India). This inflow proliferated rapidly after the 7 Emirates became a Union in 1971, coupled with the oil boom in 1973.

To put things into perspective, between the late 1960s and 1980, the population of Dubai rose from 59,000 to 279,000 while Abu Dhabi expanded from 44,000 to 420,000. Therefore, the demographic supremacy of expats over the locals existed ever since UAE’s independence. In this initial period, there were many Arab’s in the workforce from countries like Palestine, Yemen, Jordan, Egypt and so on.

But, unfortunately, due to exogenous international events like the rise of “revolutionary” ideologies such as Nasserism (and Baathism) in Arab states, the Iranian Revolution (1979), and the Gulf War (1990-1991), the UAE clamped down on recruiting Arabs and instead brought in cheaper workforce from Sri Lanka, Philippines, and other Asian countries.

In the 2000’s, the UAE enjoyed double-digit growth due mainly to soaring oil prices – this acted as further incentive to bringing migrant workers to the country (including people from Arab states). Each emirate designed a separate master plan, which focused on how to progress in the future.

In the GCC cities, conversely, there is a xenophobic mentality that has been advanced by the monarchs, to reinforce a national identity among the locals at the expense of non-citizens.

From tourism to construction, telecommunication to media, all these distinct blue and white-collar jobs needed to be performed and hence more migrants were invited. During this time, Dubai diversified its economy by creating ports, financial sectors, and improved its service industry. From 1995-2005, Dubai’s population doubled and its size quadrupled.

In the same period during and after 2000, a drive for Emiratization also began. Emiratization aimed to reduce the dependence on foreign labour by increasing the participation of Emiratis in the private sector. This was and is a quota-based drive and has been criticized for giving preferential treatment to Emiratis in the job market.

While Emiratis are still minimally present in the private sector (although they are paid higher salaries than expats), they are in copious amounts in the public sector. The UAE monitors and regulates migrants through the infamous kafala (sponsorship) system. The kafala system has been cited by many human rights organizations as immoral and unjust especially towards lower-class workers. The system entails that an Emirati must sponsor anyone who wants to work in the UAE.

Read more: Citizenship of Pakistan- stricter rules and a dilemma for minorities

The migrant hence becomes dependent on his/her kafeel (sponsor who is usually also the employer) and any desire to change jobs, or go back home becomes an arduous challenge as the kafeel is responsible for his visa and legal status. Unskilled labourers are mostly exploited by their kafeels as they confiscate their passports.

In the UAE, like in most Gulf countries, there is a phenomenon present labeled as ‘tiered citizenship’ with respect to the local citizens. Dr. Manal A. Jamal – an associate professor of political science explains this trend in Dubai by asserting that there are three categories of locals: the first are the ones who have ‘the family book’ (khulasat al-qaid – documents that prove lineage) or are given citizenship by the state – these people have full citizenship rights.

The second category includes locals who have passports but not the ‘family book’ – these locals are not granted full citizenship. Lastly are the Biduns who are unregistered former nomads – this group as mentioned before have little to no rights and are not considered citizens (or at least full citizens).

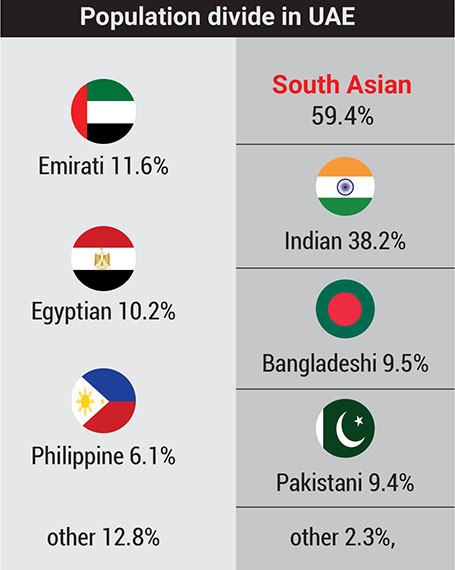

As there exists a hierarchy among the local citizens, so is one present for the expatriates. Dr. Manal states that the ‘hierarchization’ of expat communities prevails due to the UAE controlling migration flows (issuing or rejecting visas and giving preferential treatment to some communities in the public sector) in order to establish that no one community dominates.

The UAE monitors and regulates migrants through the infamous kafala system. The kafala system has been cited by many human rights organizations as immoral and unjust especially towards lower-class workers.

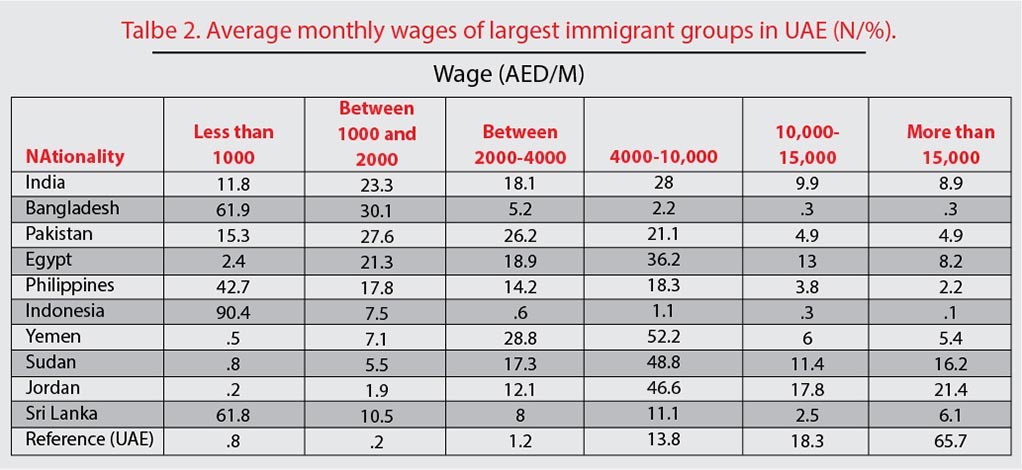

According to Professors Ed Malecki and Michael C. Ewers, there is a ‘trichotomous’ social partition, which comprises of local Arabs on the top, Western expats (skilled) below them, and lastly semiskilled South Asian workers. Notice the nuances in Malecki and Ewers’ statement i.e. the trichotomous partition has everything to do with a social class pyramid while simultaneously relying upon nationality to determine where individuals are placed on that pyramid.

Expanding upon how nationalities play a role in the UAE (and in most Gulf countries) workplace, it is an inverted world where racial discrimination is ubiquitous. Albeit with exceptions, there are certain nationalities that dominate specific industries and job types in UAE – Pakistanis in the transportation sector, British and Irish as managers and CEOs, Filipina women as maids and nannies, Indians and Bengalis in sanitation, etcetera.

The trend being that higher-end jobs are earmarked for Europeans while lower-class jobs are destined for South Asians and other minorities – this is not accidental. The UAE, its institutional arms, and companies, state-owned and otherwise, are guilty of supporting systemic religious, racial, age-based, and gender discrimination in the workplace.

An Italian expat being interviewed by The Gazelle, a student publication, noted that it is commonplace to witness ethnically discriminatory job announcements in Abu Dhabi and Dubai. The same expat stated that Asians are given less money for the same job compared to Europeans: “I worked from 9 am until midnight, twice a week, and made around AED 5,000. They [Asians] got AED 3,500 for the same job.

They were mainly from Pakistan and the Philippines… I can guarantee that many promotional or hostessing companies only want Europeans or Western-looking people”. Although this kind of behaviour was recently outlawed in 2015 by the state, it is still prevalent. Even today, if one does a quick scan of UAE’s job market, he/she will unearth rampant discrimination – from wanting an experienced Filipina nurse between 28-32 to asking women with hijabs not to apply.

Read more: Biharis: Their crime was their belief in Pakistan – Sultan M…

Author Syed Faiz Ali states that the transient nature of migrant stay is different for labourers, middle-class, and professionals – labourers are dealt with extreme strictness (passport confiscation, wages withheld, etcetera), while the middle-class and professional strata are accommodated much better (higher salaries, luxury accommodation, and so on).

In my primary research, 12 of the 19 cabbies stated that some permutation of the RTA (Roads and Transportation Authority), taxi company, and police were the biggest problems afflicting the drivers.

One driver even quit due to the strict and conflicting rules of the police and RTA. When I asked him if he was satisfied with his departure, he smiled and stated “I offered prayers of gratitude after I quit. I was sick of RTA’s rules.” Another stated, “I am not happy at all. They have increased the target [revenue goals set by companies]. The fines we get are very high. They deduct accommodation and food charges from our pay as well.”

The trend being that higher end jobs are earmarked for Europeans while lower-class jobs are destined for South Asians and other minorities – this is not accidental.

Some drivers mentioned that due to RTA and the police’s contradictory rules, the drivers suffer. One of the drivers stated “We have to keep a lookout for customers at all costs. We are stressed about the police. We have to pay attention to the road signals. We are stressed about RTA. They have lots of rules.”

Another driver poured his heart out by saying that taxi driving was the most difficult job and that he was not happy at all. Most shockingly, when I inquired when he last went to Pakistan, he replied: “I went after 3 years this time. I got the job after 8-9 months. Then I had to go through training and all of the other processes. My father passed away and I could not go to the funeral. Two of my brothers got married and I could not attend. I could only take 2000 AED with me when I did go.”

This highlights the rigidity and inhumanity of Dubai’s institutions especially when it comes to lower-class workers. The driver was stuck due to the tedious process of becoming a taxi driver. More importantly, he could not leave even if he wished, due to his passport being confiscated by the taxi company.

Not just that, in Dubai, suppression is to the level that any resistance shown such as strikes or protests lead to heavy fines, jail time, and even deportations. I once travelled to a labour camp, the sarcastically named Sonapur (land of gold), that has been the subject of international documentaries as well as academic and media scrutiny due to its appalling living conditions.

Due to the inimical lifestyle, Sonapur is nestled strategically on the city’s periphery, away from Dubai’s spectacular Burjs, Souqs, and malls. However, one not need to travel to the fringes in order to experience the dark side of Dubai.

Within the city itself, I was shocked to see the pathetic living conditions as while interviewing one of the drivers, in Hor Al Anz, I sat in his room, which had 4 triple bunk beds and housed 11-12 people. There was no furniture besides the beds, which took 80 percent of the tiny room’s space.

This is all that they could afford and due to Dubai’s exorbitant rent prices and their minimal pay, a dozen of them were sharing rent. I can never forget what my friend stated to me that moment – “Sarmad, this is the real Dubai”. It reminded me of Architecture professor Yasser Elsheshtawy’s concept of ‘everyday spaces’ in Dubai.

Read more: Modernity, politics, and Islam: A discussion with Dr.Raghib Naeemi

While, the official city portrait exclusively highlights ultra-lavish areas such as the Palm Jumeirah, Downtown, and Marina in lieu of Satwa and Deira, it is in the latter ‘everyday spaces’, where the common person lives and negotiates his survival in the city. Although expats, from the bottom of the social pyramid to the top, have shaped the modern nature of Dubai and the UAE, most feel a sense of unbelonging.

This can be explained by the exclusionist and discriminatory policies adopted by the Gulf States. Associate professor of Anthropology, Neha Vora peaked my interest with two articles. In the first, she has interviewed middle-class Indians in Dubai, and remarks that they identified themselves not as Emiratis but as Indians based on linguistics, religion, and other factors.

Author and professor, Ahmed Kanna, explains this identity creation in the local landscape as Arab identities being shaped in opposition to non-Arab identities. The formation of these identities can also be comprehended through the concept and exercise of citizenship in the UAE.

In the same article, Vora finds that many middle-class Indians consider Dubai as an improved extension of India but ironically feel no belonging – her respondents also stated that discrimination is widely prevalent as Dubai gives preferential treatment to ‘goras’ (white people) and claimed these white folk discriminate against Indians. They too mentioned how Indians are paid less for the same jobs as compared to Europeans.

One of the drivers stated “We have to keep a lookout for customers at all costs. We are stressed about the police. We have to pay attention to the road signals. We are stressed about RTA.

As Vora’s middle-class Indians felt an immense scale of unbelonging in Dubai, so did the lower-class Pakistani cabbies. I remember, pre-thesis, all drivers I talked to desired to go back to Pakistan if a better job was available. Their reason for stay in Dubai is purely economic – these drivers are here to make money and send it back home to their families.

Therefore, Dubai was forced upon them and they, in turn, were forced to experience a Dubai deprived not only of comfort but more ominously devoid of humanity. Vora’s second article was on Indian elites (businesspersons). She found that elites acted as unofficial citizens because they helped preserve the status quo in Dubai.

She mentions that the government and these elites are complicit in creating economic and social stratification, which benefits citizens and elites while maintaining a highly problematic system of labour migration for the majority of foreigners in Dubai. Furthermore, these Indian elites, unlike their middle-class compatriots, felt like they belonged as Indians in Dubai due to their excessive role, and self-segregated space to be Indian.

This is a striking illustration of how the same nationality, in this case, Indians, has different feelings and roles based on their social class (middle-class versus upper-class); middle-class Indians do not feel like they belong and instead feel discriminated while the elite Indians enjoy their crucial socio-political role and feel integral to the dynamics of the city.

It thus becomes important to note that although nationality matters, how high one is on the socioeconomic ladder is also of equal prominence. In conclusion, it is apparent that nationalities, citizenship types, and class are reified in GCC cosmopolitans especially Dubai. Due to official citizenship eluding expats, their national and ethnic origins become visible and imperative for better or worse, depending upon their social class.

Therefore, who is from where, who belongs to which class, and who is a citizen or not, are questions of prodigious implications. On the proverbial surface, the cities appear to behave as true cosmopolitans would – characterized by a lack of social unrest, religious and national diversity, and a modernly developed urban space. However, digging deeper reveals the ugly reality of how citizenship, nationality, and class allocate one’s place in society and literally in the cities.

Mr. Sarmad Ishfaq after finishing his Masters and receiving the Top Graduate award continued his passion for writing and is a researcher for Lahore Center for Peace Research. Sarmad has several publications in international journals and magazines in the fields of Terrorism/Counterterrorism and International Relations.

The views expressed in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Village Space.