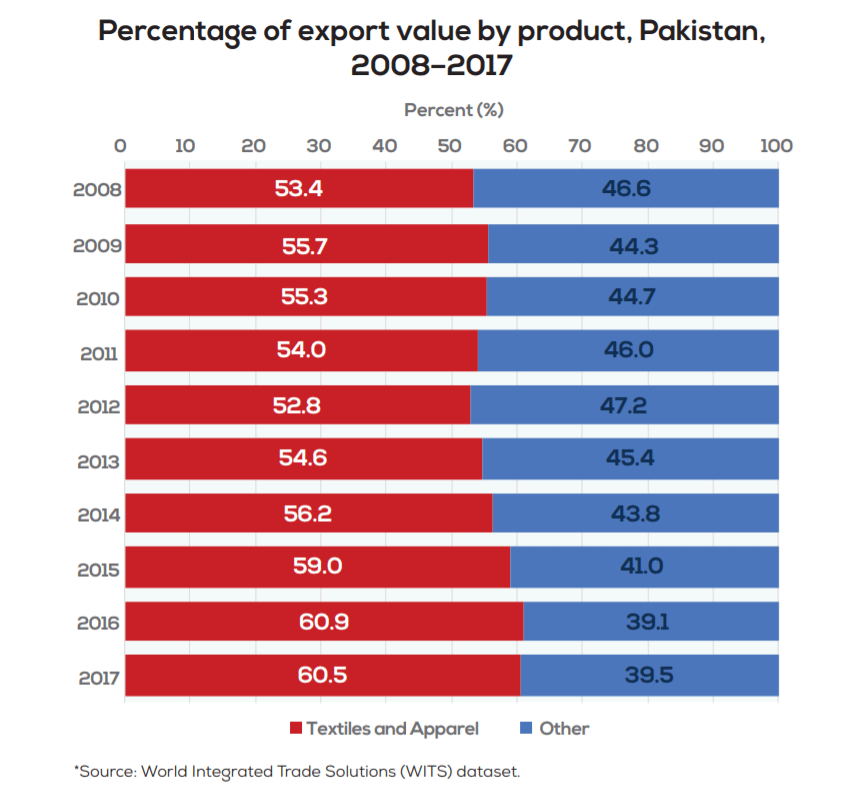

Pakistan’s export basket has not changed much over the last 500 years. In the 16th century, the Indian subcontinent was known for its silk and brocade products, embroidered cloth, precious stones and spices. In the 21st century, more than 50 percent of Pakistan’s exports still relate to cotton, textiles and clothing, while another 20 percent account for cereals, rawhides, cement, salt, sulphur, stone, leather and related products.

This narrow export basket is a reflection of our rudimentary industrial base. Despite the country’s significant size and massive population, our local manufacturing footprint remains confined to low-tech products, catering only to basic human needs of eating, clothing and shelter. Probably, the most complex commercial products that the country produces are refrigerators, air conditioners and automobiles, with high reliance on imported parts.

Rich countries exports vs poor countries exports

Many would argue that as long as the country has a decent export volume, the export composition should not matter. This, however, couldn’t be further from the truth. Export composition and industrial sophistication can define our path to prosperity. Hausmann, Hwang and Rodrik, three eminent academics, have argued that there is a clear differentiation between exports of rich countries versus poor countries.

Read more: Pakistan’s Exports – Unexpected surge amidst new opportunities

They concluded that countries specializing in more complex and high-technology goods are likely to grow faster than their peers, while the countries that stick to the ‘poor-country exports’, primarily comprising less sophisticated and low-technology goods, are likely to remain poor. As interesting as this proposition sounds, it is also quite intuitive. Richer countries claim a higher value-added due to their exports being more sophisticated and develop specialized capabilities to produce these complex goods, which connect them to several other product categories.

For instance, if a country exports computers, it can easily diversify into other electronic goods such as TVs and mobile phones. On the other hand, if a country is exporting cotton or textiles, it may not have the requisite transferrable capabilities applying to a wide variety of other product groups. The more sophisticated and high-technology industrial base also requires superior human resource and knowledge base, creating a competitive advantage. That is why economists claim that ‘countries become what they produce’.

What drives premium?

Therefore, what we export in turn defines what value we can command for them. High-tech, sophisticated or exceedingly differentiated products on the back of high-quality brands drive a much higher premium than low-technology, simple or commoditized products. The more value they command, the more their producers can invest in their manufacturing capabilities and workforce skills, enabling them to make even more complex products.

Read more: Pakistan’s exports to China crossed $300 million in December 2020: GACC

The improved capabilities thereby create higher barriers to entry and a sustainable competitive advantage. For simpler low-tech products, there are lower barriers to entry, thus creating fiercer competition, which in turn drives the prices down. The labor force making low-end products also remains poorly skilled, thus preventing the country from moving into more sophisticated products.

As a result, high-tech or sophisticated industries like mobile phones, computers and high-end luxury products are driven by innovation and differentiation. In contrast, low-tech industries like textiles and agricultural products are characterized by tariff wars and cost reduction. This is precisely what’s happening with Pakistan.

Crux of the calamity

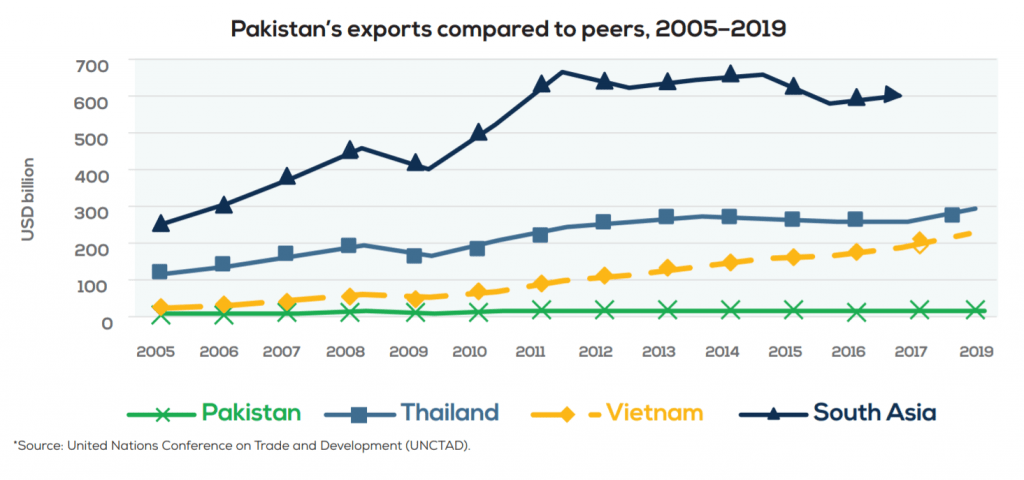

The real reason behind our low and often declining exports is our narrow export basket, primarily dominated by low value-added primary and intermediate goods, destined for a handful of markets. Unfortunately, Pakistan does not have the requisite skill base to take a quantum leap from textiles to mobile phone or computer manufacturing, notwithstanding any rhetoric, and thanks to decades of flawed policies. But the good news is that it is possible to break out of this vicious cycle. Almost all developed countries have leapfrogged into high tech exports.

Read more: Adopting Export-led Strategy for Sustainable Growth

The case of South Korea is particularly interesting. Only half a century ago, three-quarters of the country’s exports came from commodities and processed foods. Targeted policies and incentive structures transformed the industrial landscape, with manufactured goods claiming almost 90% share in exports by the mid-’80s. With the country leapfrogging from one product category to another, this growth trajectory continued, culminating in South Korea now being a leading exporter in semiconductors, wireless telecommunications equipment, motor vehicles, computers, and ships.

Even middle-income countries like Malaysia, Indonesia and Brazil have significantly improved their export composition over the last few decades through consistent and targeted policies. But this transformation can’t happen overnight. Decades of mistakes will at least take years to fix.

How can Pakistan transform?

To begin with, the economic policy-setting in Pakistan would need a paradigm shift. The government should single-mindedly pursue diversification, value addition and industrial sophistication, with industrial, trade and investment policies all targeting product and market diversification, and all subsidies and government support limited to industries pursuing differentiation or up-gradation. Such a paradigm shift should focus on three main priorities, reflected in a brand-new overarching industrial policy:

• Discarding the notion of level playing field and instead of making the field favorable for winning sectors.

• Limiting government’s direct interventions and investment to only addressing market failures.

• Promoting participation in global value chains, in turn catalyzing technology transfer.

Be biased: Choose winners!

The first and foremost step is to pick and choose high-technology priority sectors for future government support rather than subsidizing exports across the board. This essentially means going against the popular notion of level playing field and rather preferring winners over losers.

Read more: A look back at Pakistan’s exports in 2020

Once these sectors are identified, the government should provide incentives to stimulate investment in these technology-driven priority sectors. Providing incentives would encourage more entrepreneurs to develop capabilities in selected sectors and offset their initial investment requirements, making the proposition more viable. Such incentives can come in the form of rebates for selected sectors, zero-rating of inputs and capital equipment and other tax discounts.

Governments resolving market failures

Over the years, the government has dabbled into wide-ranging interventions to support the private sector, ranging from undertaking skill development projects to establishing common facility centers, and from facilitating participation in trade fairs to establishing business parks and industrial estates. However, going forward, all such investments should only be limited to addressing market failures in priority sectors.

Read more: Challenges of ‘Made in Pakistan’

In simple terms, an investor would not invest in an IT manufacturing facility unless there is well-trained human resource available. On the other hand, the service providers would not offer relevant IT skills development programs unless there are sufficient employment opportunities, creating a permanent void. In order to address this issue, the government needs to take the lead and invest in requisite capabilities that can address such challenges for individual investors, simultaneously creating supply and demand.

Catalyzing technology transfer through GVCs

Last but not the least, Pakistan should enhance its participation in regional and global value chains (GVCs). GVCs are international production networks, with the production of a single product shared across different countries that build competitive advantage in a small sub-section of the supply chain. While GVCs help multinational corporations reduce their costs and improve the quality of their products, they also enable participating countries to integrate into global markets without developing the full value chain’s know-how.

GVCs rest on a detailed exchange of information, technology and components, and deep supplier relationships much beyond the traditional knowledge transfers of the past. Many countries have used GVCs to enhance their industrial sophistication. China, for instance, successfully used its low-cost labor to partner with leading international corporations, selling to consumers around the world, and in the process, improved its own technological base and economic sophistication and became the world’s largest exporter.

Read more: Strengthening Cooperation in Trade, Industry: Leveraging CPEC to Double Textile Exports

Pakistan is not altogether new to GVCs. Pakistan’s auto part manufacturers do participate in GVCs of car manufacturing industry, but they are still confined to the periphery of this vast GVC, being secondary contractors to these Tier 1 suppliers like Denso and Saint-Gobain. There is a need to deepen such participation. This could be done through targeted trade policy measures, openness to FDI, lower import costs, efficient trade and logistics infrastructure and facilitation, intellectual property protection and a friendly business environment.

While it may be difficult to immediately remove distortions in all these areas, the planned Special Economic Zones (SEZs) can play a great role to create a micro-investment climate enabling GVC participation for local firms, supported through targeted investment policies. These could then have spillover effects for other firms in the country, enabling Pakistan to move up the technology ladder from exporting raw materials to products with greater value addition and increased sophistication.

But all of this is easier said than done. It means taking away generous incentives from industries that keep on exporting the same products year after year, and instead diverting them to incentivize newer product categories and innovative technologies. This may also mean hurting interests of established industrial lobbies and leaving the rent-seeking industries on their own.

Read more: Top 6 Exporters of Pakistan

It would also mean supporting products and activities that have no or few supporting lobbies. In short, what we need is a new proactive industrial policy for the next decade, which targets increased economic complexity and innovation, rather than blindly pursuing export growth through subsidizing run-of-the-mill export products.

Hasaan Khawar is an Islamabad-based international development consultant with 20-plus years of experience in both the public and private sector. He is currently the team leader of the DFID funded Sustainable Energy and Economic Development (SEED) project and holds honorary positions in various other enterprises. He is a former civil servant and a frequent advisor to the government of Pakistan. He tweets @hasaankhawar – The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Village Space.