Zahra Khan | Nov 15, 2016

Similar to today’s contemporary culture, pictorial representations in early Islamic manuscripts and literature were highly influenced by social and political influences. Even illustrations of animals and mythical creatures were dependent upon and indicators of cultural movements. There are three mythical creatures that are predominantly represented in Islamic Art, the Islamic Sphinx, the Phoenix and the Dragon. Their depictions transformed over time and with the advent of foreign influences, and became increasingly representational with embellishments of vivid colours and gold.

The dragon, in particular, has been portrayed throughout the ages and in a variety of mediums. Four dragons appear in one of the most famous astrological treatises from that period: Abu l’Husayn ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn ‘Umar al Sufi Al-Sufi’s Kitab Suwar al-Kawakib al Thabitah, or the Book on the Constellations of the Fixed Stars (c. 964). Al Sufi was a Persian astronomer who lived during the 10th century. This particular manuscript is based upon his translation and reworking of the 48 classical constellations of Ptolemy’s the Algamest, and has had a lasting impact on Astronomical and Astrological observations.

Arab variations of the dragon trickle through Central Asian and Persian sources. Most Central Asian depictions represent dragons as positive yet powerful beasts; however Persian sources characterize dragons as evil and malevolent. Due to these two contradictory sources of dragon myths, dragons in Arabic literature and art can be ambivalent – some variations possessing positive qualities while others identify the negative qualities. Most of the figurative characteristics associated with dragons, such as horns, wings and elegance, have come directly from Asian illustrations. Dragon lore claims that dragons are able to alter shape, and has represented them with legs, and without legs, with wings and without them, as creatures of water, or of land. It was widely believed that snakes were the undeveloped versions of dragons.

The dragon in early Islam symbolizes chaos and disorder; this correlation appears to stem from the early Babylonian and Mesopotamian myth of Tiamat, the sea-monster, which was a fantastical female creature with wings. She was sliced in half by a hero who created the heavens out of her top half, and the earth out of her bottom half. The evil nature of the dragon, and the interchangeability between forms, may also stem from the narrative of Adam and Eve – a beautiful serpent which was reportedly the size of a camel with four legs, allowed Satan to hide inside of her, and tempt Adam and Eve with the Apple. The serpent then lost her legs and was banished from Heaven as punishment.

Representations of dragons were not only limited to astrology or the celestial skies. Depictions of dragons and serpents in ancient manuscripts became more refined and much more reptilian between the 11th and the 15th centuries. This move towards more reptilian imagery is due to a number of reasons, stemming from the inclusion of dragonian imagery in culture and literature. After the advent of a steady influence from central Asia, dragon-lore became ingrained in the fabric of cultural traditions. Dragons were written about in Persian literature, such as the Shahnama or the Book of Kings of Ferdawsi, written by 1010 AD. The Shahnama was an epic poem, which narrated the glory of Persia before the introduction of Islam. It contained mythological creatures and historical references, and included stories of heroes fighting dangerous beasts.

The Aja ‘ib al-Makhluqal (Wonders of Creation) by al-Qazwini also depicts Al-Sufi’s constellations. In addition, the manuscript has descriptions and paintings about animals and mythological creatures including five dragons. Here too, the dragon is thought to be a “a large and ugly creature, long and wide with a huge head, fiery eyes, an open hollow mouth, and many teeth, that swallows almost all animals.”[1] The implications of this description are far more weighty when the contemporary audience of this manuscript is considered. Scholars believe that the characteristics of the dragons were also metaphorical; Qazwini’s manuscript is from 1280 AD, this means that his students had lived through the Mongol conquests. They were well aware of the ferocious power of the dragon.

The celestial planets and constellations, particularly the signs of the Zodiac, were said to possess supernatural forces. Over the passage of time portrayals of dragons acquired talismanic or protective characteristics. They were based upon the celestial constellation Draco, the images of Al-Jawzahr, the dragon-like eight planets, and the illustrations of Chinese dragons, which were currently introduced into Islamic art. Dragonian imagery was believed to have powerful magical powers, and eventually symbols of dragons were included on entryways and gates. Dragon heads were also sculpted on to the staffs of Kings – this association with the power and prestige of a Dragon would imbibe the King with additional control.

There is dragon-like imagery in four constellations in Al-Sufi’s manuscript. The images below are from the manuscript Kitab Suwar al-Khawakib al-Thabitta currently held in the Paris Bibliotheque Nationale, MS Arabe 5036, Fol. 34. It has been dated to 1436 AD. Its images are far more delicately rendered, and are far more intricate than those in older, surviving copies of the treatise, in particular MS Marsh 144, held at the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. The Bodleian manuscript is believed to be the oldest surviving illustrated manuscript in Arabic. It is widely believed that this manuscript is the copy made by Al-Sufi’s son, and was completed between 1009 – 1010 AD.

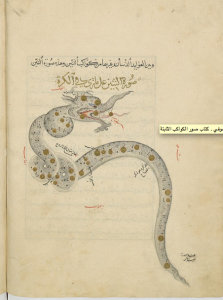

Draco: Draco the Dragon is usually portrayed as a long snake, with one to three coils, with a forked tongue and a jaw full of teeth. The earliest version of the Al-Sufi manuscripts shows Draco with pointed ears, while later versions depict “long trailing eyebrows and a beard,” and Draco’s teeth and jaw are pronounced.[2] Gold is used to represent the stars within the dragon, but careful attention is paid to his features. Red and orange is used on the outside of his mouth, his beard and upper jaw is curved. The scales on his skin and although the dragon itself is primarily grey, the artist as utilized blue and red to paint his piercing eye. Draco is in profile as his pink tongue juts out. True to description, Draco has three twists in its body.

Figure 4: Draco, Paris Bibliotheque Nationale, MS Arabe 5036, Fol. 34. [3]

Serpentarius: The illustrations of this constellation often show a man “with strangely squared shoulders” (because of the placement of four stars), holding a snake in both hands. This snake coils behind the man and has a forked tongue in a toothy jaw.[4] The artist has used a broad and cool colour palette to represent Serpentarius and his Serpent; there are pale blues that contrast with the bright red and gold of the stars. Each detail in this image is carefully accounted for, from each of the toes of the figure, to Serpentarius’s Asian-like features. The Serpent’s reptile-like snout and pale blue tongue are thin and curved. The labels on the stars and the scales on the serpent’s skin assist in making the image even more beautiful and intricate. The pale blue of the serpent’s tail, the blue of the scales on its head and the blue on the underside of Serpentarius’s clothes enhance the grandeur of the piece.

Figure 6: Serpentarius, Paris Bibliotheque Nationale, MS Arabe 5036, Fol. 81.[5]

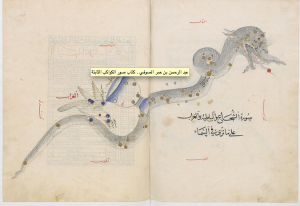

Hydra: Hydra, the sea serpent generally includes a single coil in its body. The double page spread below includes two other constellations that are close to Hydra – Crater and Corvus, both have been carefully labelled. The deep blue, gold and red spots depict the stars which form the constellation. Here too, as in Draco, there are flame-like marks around the mouth of the creature. Hydra has a beard and ears and its tongue, which contains a red star on its tip, is narrow and curvaceous. The serpent’s scales are carefully drawn in and the skin is given a bluish grey wash.

Figure 8: Hydra, Paris Bibliotheque Nationale, MS Arabe 5036, fol. 225 – 226.[6]

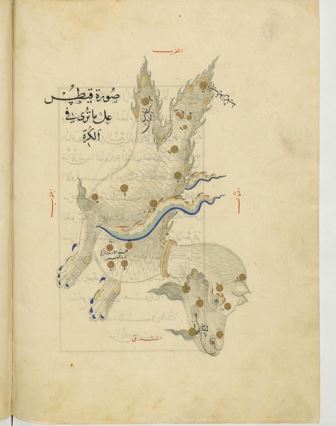

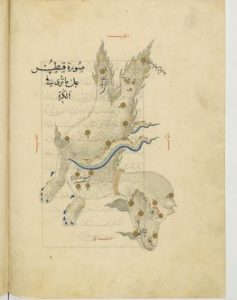

Cetus: In older versions of the treatise, Cetus, the sea monster resembled a dog-like mammal. In the illustration below, although Cetus is less narrow and reptilian than other depictions of dragons, the creature does possess dragon-like attributes. His body is covered in scales and the artist has used vivid blue, copper and gold to emphasize his fluttering, flaming tail, elaborate wings, horns and beard.

Figure 10: Cetus, Paris Bibliotheque Nationale, MS Arabe 5036, fol. 187.[7]

The inclusion and subsequent transformation of Dragonian imagery in Islamic art took place fairly quickly. It is an example of how depictions cultural art are based upon a multitude of traditions and sources. As an understanding and interest in mythological creatures grew, the creation and publication of relevant manuscripts increased as well, influences from central Asia flooded in, and representations of a previously exotic and unknown concept became embedded into the fabric of traditions and customs.

Original article appeared on Art Now

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Global Village Space’s editorial policy.