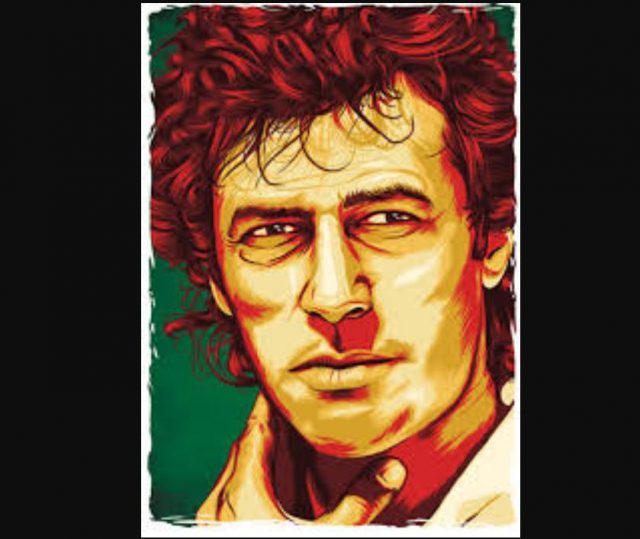

Sher Ali Tareen |

Of all mainstream political leaders, Imran Khan deserves the fiercest and most vigilant critique whenever he errs or transgresses on any count. This is so for two reasons. One is the high standards he has claimed for himself, that in his view distinguish him from his competitors. And two, the nation can ill-afford Imran to fail. Thus, the productive critique that betters him as a leader is good for him and for the country. However, there is a massive difference between robust critique and unfair and exaggerated attacks, based on decontextualized, selective, and mean-spirited readings of his actions and statements. Let me briefly reflect on two recent moments to make my case.

Let us begin with the recent Zulfi Bukhari saga. Bukhari, Imran’s close friend of around seven years, was accompanying the latter on a trip to Saudi Arabia for Umrah. However, he was barred from flying out of Pakistan as his name was put, without his knowledge, on a “black-list.” Why? Because, he owns some off-shore companies, and thus became subject to a NAB inquiry, despite his status as a British national who conducts none of his business in Pakistan. Bukhari henceforth appealed to the Interior Ministry that he be granted a one-time waiver and be allowed to travel. After a few hours, this request was granted and he proceeded onwards to the city of the Prophet.

Read more: Workers protest infront of Imran Khan’s residence; police, rangers deployed

Meanwhile, back in Pakistan, all hell broke loose. Unsubstantiated narratives entangling the weight of Imran’s influence to Bukhari’s clearance were weaved with feverish velocity, on social and electronic media, as powerful journalists/anchors skewered Imran night after night with abrasive attacks and mockery. He was duly pronounced the banner-bearer of nepotism, promoter of VIP culture, abettor of corruption and corrupt people (note that there is no indication that Bukhari has broken any law), a hypocrite, and equal to if not worse than Nawaz Sharif and Asif Zardari. In retrospect, turns out, these were all hyperbolic innuendos, with little substance or evidence. From the available evidence, it seems clear that Imran had not made any calls to the Interior Ministry, or used his influence to rescue his friend; the due process was conducted independently and in accordance with official procedures. Bukhari, for his part, came back to Pakistan within a few days and is facing the NAB inquiry. Certainly, raising the question and suspicion of nepotistic conduct was absolutely correct and justified, but issuing damning verdicts of culpability without corroborative evidence was equally wrong and unfair. The underlying ingredient missing from these media trials is that of proportionality. Even if it were true that Imran had indeed sinned in this case by serving as his friend’s intercessor, equating that sin to the long-running monstrous thuggery and putrid dynastic nepotism of the likes of Nawaz, Zardari, and their manicured progeny is despicably disproportional. Yes, Imran must be put to higher standards of conduct than his rivals, but again, there is a massive difference between vigorous critique and hyperbolic character assassination.

Let me turn to another and more sensitive example: Imran’s recent comments on ‘western’ feminism and motherhood, aired during a recent television interview. The context of this interview, and of his comments, is important to consider. During an Eid special interview on Hum News, in the course of extolling his own mother and former wife, Imran said fleetingly, almost as an after-thought: “I am against the western feminist movement that has degraded motherhood.” This was not a carefully formulated thought, much less a policy statement. Most likely what he meant, misusing the term ‘feminism,’ is that he does not agree with visions of women’s agency that pivot on the abdication of motherhood. If one were intellectually charitable, one may read his statement as an argument for modes of power and agency derived not from resisting or overcoming but cultivating disciplined practices of care like motherhood. But most likely, this subtle critique of certain strands of western feminist thought was not on Imran’s mind, hence rendering his statement unfortunate and indefensible. His generalization of ‘western’ feminism is only partially the problem here. More regrettable is his inability to approach justice, the value that holds together his politics and party name, as intersectional. Justice for the impoverished crippled by a corrupt elite, justice for the collateral human victims of drone attacks slayed by imperial power, and justice for victims of misogyny at home and elsewhere – these are all intersectional causes that are intimately interwoven. Imran would do well to adopt a more capacious understanding of justice with a central place for gender-justice. Just as one can be critical of western imperialism while borrowing aspects of western governance, as Imran so beautifully does in his politics, one can and should be critical of western imperial feminism driven by the mandate of ‘liberating’ oppressed ‘Muslim women,’ and yet be inspired by the many achievements of the feminist movement. There is no reason that with some reflection, he will get this point. He is not the dimwit his liberal detractors so relish portraying him as; an imbecile could never have achieved and accomplished all that he has.

Read more: Ex-CJP Iftikhar Chaudhary to file case against Imran Khan over Sita…

But while Imran’s statement was worthy of rebuke, it certainly did not equate to an argument for confining women to the home or tying their value as human beings to motherhood. Certainly, Imran is no radical feminist; one wishes he were one. But so is he not the vile sexist, diabolical misogynist, anti-women patriarch, advocate of domestic enslavement, women eraser, and adversary of women’s participation in public life that he was made out to be in countless editorials, opinion pieces, and social media posts in the days following the interview. Such characterizations are rather misplaced and unwarranted. These readings participate in an exercise of interpretive gymnastics that take his pithy statement to remote pastures of meaning; he would have had to speak for at least a few more minutes with quite a bit further elaboration to qualify for such imputations. The larger point is this: he did not advance a blanket condemnation of feminism or present a normative argument for the containment of women to motherhood or domestic life.

If anything, his record as a public figure and politician strongly mitigate against such caricatures. More than any other political party in the country, the PTI has consistently mobilized and attracted urban women (in some instances even rural women) in massive numbers from multiple class backgrounds to its rallies, now for almost a decade. Other than unprecedented environmental development, among the most brilliant aspects of the successful billion tree tsunami campaign were the major and innovative employment opportunities and in effect, avenues for empowerment it offered underprivileged women in KP. The KP police force has been a pioneer in the recruitment and retention of female commandos. And most recently, Hamida Shahid, PTI’s nominee for the provincial assembly in the upcoming polls, is set to become the first woman in Lower Dir to ever contest elections, in a region and constituency where it is rare for women to even cast votes. These are hardly the acts of a draconian sexist. Again, to repeat, what Imran said was problematic, and cried out for interruption and correction. But striking the sledgehammer of blasphemy on the slightest hint of heresy from liberal orthodoxy is not particularly conducive to furthering the conversation either.

Read more: When Imran Khan Rules Pakistan

Imran is unique among the current crop of political leaders in enjoying a following that cuts across diverse segments of the population, ranging from pockets of the English speaking urban elite to residents of rural KP, from middle-class university students to madrasa graduates, from farmers in Punjab to professional overseas Pakistanis. This sort of support provides him with an outstanding opportunity to mend the ideological polarization, especially on sensitive political and moral questions that afflict the country. He will thus do well to calibrate his discourse in a manner that expands rather than contract the tent of his movement for justice. On the other hand, Imran’s critics will also serve the cause of nuanced discourse better by distinguishing vigorous and unforgiving critique from disproportionate attack and ambush.

Sher Ali Tareen is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Franklin and Marshall College, USA. He received his Ph.D. from Duke University in 2012. The views expressed in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Village Space.