GVS: When did you join the army and where were you in 1971?

Gen. Asad Durrani: October 1960. That’s the day we passed out. At the time of the war I was doing staff course, Quetta 1971, which started in January-February. The war started when we were there, and once the war started, the course was terminated. People got posted to different places. A couple of our colleagues did get posted to East Pakistan. At that time, I was not; lucky or unlucky, whatever one was. Those who went there, most of them came back after two years via India.

GVS: Did you understand what was happening in East Pakistan?

Gen. Asad Durrani: Actually, one could see that the situation was pretty bad for a number of rea-sons. Even before those elections [1970], there were rumblings, people were restless; but after the elections, the expectation was that we would abide by the results despite President Yahya Khan and Zulfiqar Bhutto. That might have been a good thing. But since we probably did not intend to and that is what the history has now taught us, there were roadblocks put in front of that arrangement, by Bhutto and Yahya Khan, so it was not going to happen.

Then the military action took place, and we got further worried, because one knows pretty well, even at that time anyone who was in that business of looking at the things in their historical perspective in the actual thing would have said, No, it’s not going to be right. Military action at this time was out. I mean, Sahibzada Yaqub Khan, the person who was in charge there, also sent a message, don’t do it, that time is over, if at all it was ever there. Now it’s going to be a political settlement, but it didn’t happen.

GVS: Was there a consensus on the military action that happened on 25th March 1971?

Gen. Asad Durrani: Most of us did believe that the military action was not called for. There were some who said, No, we should do it. I remember some of my colleagues saying, well, Sahibzada [Yaqoob] Sahab because of his academic background, and so on was making hypotheses. Then came the man from the Salt Range, Tikka Khan, and he sorted them out.

Once he had contained the insurgency, latest, by that time, the time had come to start negotiations; a political settlement, that’s the teaching, that’s always been the teaching. The military’s role is only to contain a situation, not to try and resolve it. I mean, in insurgencies and in guerilla warfare, in Afghanistan, we have seen, the military’s job is only up to that extent, that you try and provide space and time to the political leadership to find a political settlement.

Once Tikka Khan came back, and Niazi went, he again, true to his reputation, wanted to do only the kinetic thing and wanted to go all in all with his military. That was a time where everyone was worried, and a number of people said, now, it seems the thing is over.

Read more: Hasina Sheikh’s Politics: Where the fantastic Fig of Three Million came from?

GVS: Was there a feeling in army that firmer action should be taken?

Gen. Asad Durrani: I don’t think anyone at that time said that we have to crack down and finish the whole thing. Some people may have said we have to crack down a little more, take a little more action before we do that, but no one said that now we have to actually crush them to the extent that they will surrender.

No one from our group, and of course it was a selected group because those were the people who were appearing for the staff course 70-80 odd officers, selected people I mean, they have gone through a certain process, but I don’t remember if anyone said that the revolution or the revolt has to be crushed; Get hold of Mujeeb ur Rehman, that sort of thing I must have heard, but most of them said, we are on the wrong track.

GVS: Most of the country was not aware of what was happening. What about within the army – did they realize that we were losing the war?

Gen. Asad Durrani: Yes, absolutely. I don’t think there was any doubt about that. One could see the writing on the wall. Anyone who looks at that place, surrounded from three sides by India, the population turned hostile, enough number of people have joined the Mukti Bahinis, and so on, so forth. At that time to say, we’ll still bake it, we’ll still crush them, and we’ll still come out victorious that I never heard. In fact, what I heard was that enough number of people from outside even the Chinese friends and the others said, find a political solution.

GVS: What was the impact it was having on the morale of the soldiers?

Gen. Asad Durrani: As far as the morale is concerned, essentially, at that level where I was operating, the morale is of immense importance. Later on, when the course finished, we actually got involved, we went and joined the units, my unit was in that famous Rajasthan sector, and it didn’t turn out favorable for us.

At that time, as far as the people were concerned, the ranks and files were concerned; their morale was determined by how the officer was behaving. If they find their Captain Sahab Major Sahab Colonel Sahab leading well, then they are alright.

In that very difficult situation, when we were stuck in the sand dunes, this is the Longewala offensive; people probably will and could have studied it from very many different perspectives as to how foolish it was after those supports were not provided to us, the air cover the type of tractors that we needed in the sand, the water supplies that had to come when it was clear that it was not coming.

I mean, that is the role of the commander, the GOC at that time, very capable man; otherwise, he could have said, No, I’m not undertaking it because this is the recipe for failure. We are not going to succeed in this terrain with-out the air cover and without logistic support. But he had a very strange argument, and he said people should not even think that I chickened out.

Now, this is not the job of a commander, especially at that rank; in general, to say no, if he finds that the mission is going to be not only costly but also had no chance of success. He continued, and our people, of course, continued. But there, I saw the performance of the men. I crossed one of the sand dunes, and I said, this gun will not go up the sand dune, and I can see that how badly it is stuck.

After some time, I crossed it again, and these chaps had taken it up. So the people were spirited just because they were being led well, at that lev-el. Later on, once the results came out, naturally, people were not very happy. Lost the war. There was never any doubt about that.

Read more: What happened to those who broke up Pakistan in 1971?

GVS: Did you hear about any atrocities being committed in East Pakistan during this period?

Gen. Asad Durrani: I mean, we didn’t hear very much about that. We have to concede that at that time, we didn’t hear very much about the atrocities and the rapes. Later on, when all the news was coming, it was through the Indian sources, through the others. They did talk about it. At that time, people were naturally not very happy because this is not the way you treat anyone, especially your own people. We considered them our own people.

It’s much later, many years later, that one found out, basically because of the work done by Neta Jees granddaughter who wrote that particular book [Sarmila Bose, Dead Reckoning], a very famous book, the atrocities supposed to have been commit-ted by the Pakistani army were highly exaggerated. Not so many people were killed, not so many women raped, but that is, besides the point, its not the number that counts. But whenever, when we found out that these things had happened, one felt very sorry for our own people.

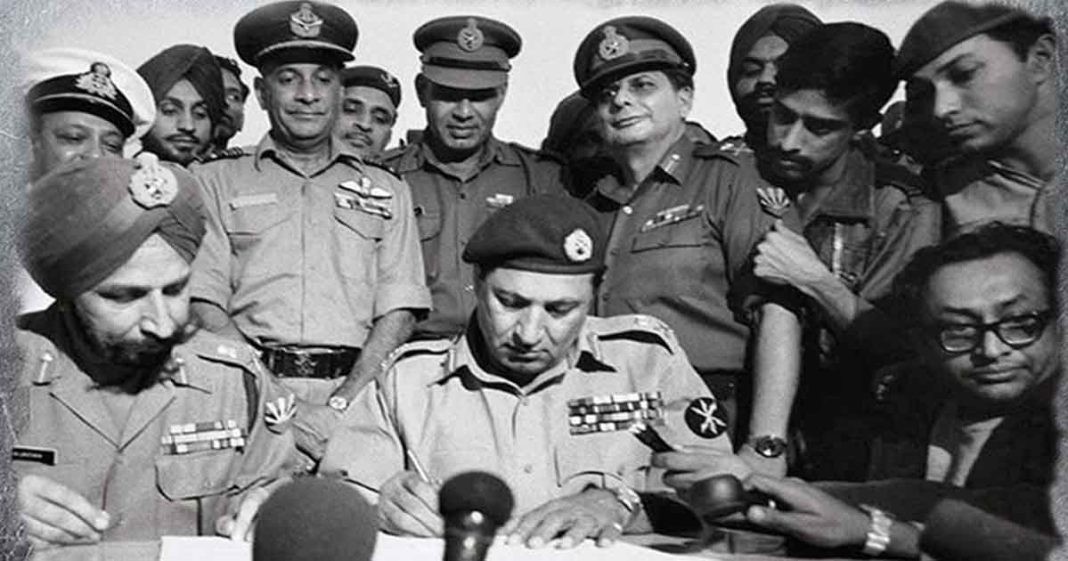

GVS: How did the soldiers feel on the Surrender

Gen. Asad Durrani: I mean, there were mixed feelings. Frankly, this is what always happens, and one saw it coming. No one celebrated it, but as it happens, very often in history, fait accompli, something has happened, and you are trying to look at any advantage that they have accrued, while these people were not going to be with us and we were not going to leave them.

“We are happy that we got rid of them” this is also something that I have heard, but anyone who had served together with them, after all we were in studies together, we were in academies together, we were in the army together, and we knew our fellow Bengalis, and they would not have said that because their feelings were not anti-Pakistan.

They did talk about, you know, a certain unfair treatment that had been meted out to them and they were more aware of whatever was happening, they would talk about, you know, how the jute was grown in East-Pakistan and exported from West-Pakistan, and the type of arrangement that we were making, sometimes denying them the majority and finally, the one unit we brought them at par they had to give up certain things.

So they were unhappy with those things, and they were very cognizant of those things. But they still were not anti-Pakistan; they did not want Pakistan Army to go and get defeated there, majority of them did not. Some of them, of course, were in the Mukti Bahinis when they thought that things that come to a head.

Read more: Bangladesh vs Pakistan: What is Hasina’s Real Problem?

But at that time to say that these people were not going to be with us or not going to be “this or that” was certainly not the right way to think. Some people probably may have said that, but the majority did say that we played a greater role in their separation than they did by not treating them well.

I think people later on also not only talked about it but started believing in it. You know, the critical juncture, not honoring the results of the election, not doing what had always been the teaching, this is how you do. So, now terribly, and that is where one came to a conclusion, we created Bangladesh like India created Pakistan.

I mean, this is something that some people have a problem understanding. After all, Quaid-e-Azam did agree to the cabinet mission plan. And now people like Advani, especially Jaswant Singh they’ve also said people responsible for the partition were Patels and Nehru and not Jinnah.

This is what happens when the majority or when the more powerful side is not willing to make that type of concession that the that’s not only fair, but that should show that you are having the history I know certain examples where the country powerful says I can give up that much. So that the other side, the weaker groups, do not feel that they have been exploited that they have a stake in the, you know, bigger unity since it was not happening.

Read more: From East Pakistan to Bangladesh: What went wrong?

GVS: Importance of personalities vs events in breakup?

Gen. Asad Durrani: Personalities would always matter because some decisions have to be taken in that time, but the events are important in the sense that in all the previous years, how many years, 24 years. I think most of the time we were the establishment here, let me say “they” the ruling parties were not giving the Bengalis their due, none of them.

It may have even started, it’s a very difficult thing to say, but it may have even started when Quaid-e-Azam said, you will also speak Urdu. Urdu will be the national language. Having two or three national languages is no big deal. But for people who take pride in that language, whose literature, in fact, was maybe richer, certainty it’s an older language. To them to say “no” for the sake of unity now Urdu will be imposed upon you. One could even have started from there.

But I think all those events could have been recovered but over a period of time when one found out that despite some of the cosmetic moves that we were used to making; getting some Bengalis in the army, which is a good thing that frankly if you ask me, and they did very well in the army, and we were very happy that they were there; create another capital in Bangladesh, the subsidiary capital, but not giving them that autonomy that people always look for.

In this case, it’s not we who were giving them the autonomy, it belonged to them, we snatched it because of the power that we had, because of the army that we had, because of the political clout, the size, and maybe overall West-Pakistan was, if we take the whole balance, more powerful than an East Pakistan, so we denied it.

Read more: Pakistan – Bangladesh diminishing hope for better ties?

GVS: Was talking on six points tantamount to accepting independence of the province?

Gen. Asad Durrani: Negotiating six points was possible. If you just take the whole package, some people say no, but that means separation, that means traitor and so you can’t negotiate that. In my opinion, in six points, you negotiate to ultimately come down to a common denominator of two or three points that are in their advantage, two or three points in which they have conceded something.

Negotiations I don’t think were done very seriously, like, next-door Afghanistan. I mean, the points the Taliban’s demands for usually start with a maximalist agenda. But you can always tone down and can bring them down through negotiations. But I think that the moment six points came up, the reaction generally across the country was; this (six points) is something that we could not expect.

Though, ultimately, I do not know if at that time we heard anyone say, let’s at least talk about that. And if the things are gone to that bad an end, then why not settle with a friendly parting or a confederation type of arrangement, at least try. And that’s what I believe is the establishment problem is that is the ‘all or nothing’. If we don’t get everything, no, we will not take it. Now the other side will not give you everything.

And if you do it very, you know, intelligently, very wisely, you might be able to clinch a couple of things to retrieve that bad situation. And that’s always been the case whether it is in Kashmir we talked about or in Palestine was a very big example. Ultimately, you know, the 2000 or 2001 package that was offered to the Palestinians to me looked good, for the time being, and if you don’t want to take it, then you get nothing.

Read more: How Pakistan was ‘Created & Lost’: A journey of ‘Blood & Tears’

GVS: With 1000 kilometers separating East and West Pakistan – was it always an idea bound to fail?

Gen. Asad Durrani: It’s not a very good situation, frankly, maybe even considered untenable, 1000 miles of hostile country in between. The only thing that used to tie the two was Islam and PIA, and later on, one found out that Islam was not enough, and the PIA got disrupted. So it was not a very good situation.

But we are talking about that particular time, 1969, 70-71, when it started, and at that time, one could have said, I suppose it will not happen. And that’s why we should part for a number of rea-sons, or can give it a better chance by accepting a few things and going even to the extent of saying, you know, confederation.

I mean, that is what Mujibur ur Rehman probably wanted. I’m sure in case of East Pakistan or Bangladesh, also, some people said, we can find a way, but making it happen, having that type of courage, bringing, you know, the detractors on board, and doing it slowly, gradually, incrementally like the European Union.

Read more: Fall of Dhaka 1971: Questioning the Iconic 3 million

All of this takes a lot of patience, and in keeping at it with the focus, and the most important thing is to get all the stakeholders. Governments will come and go, but this is the path in which we will try and handle East Pakistan; it’s possible.

But I do agree that it was not very easy, especially because of not only geography but all the whole geopolitical environment. Before, in those 24 years, we joined SEATO because East-Pakistan was there. One had not given up the prospects of creating a bigger organization in which the Eastern wing was going to play a very important role.

Furthermore, it was uncomfortable more for the Indians, those two prongs than it was for us if you ask me. I suppose the parting thought that I want to leave with your audience is. Many years later, enough number of Indians used to say, what did we gain? We helped Bangladesh attain freedom, but they cheer Pakistani teams.

They still yearn for Pakistan. They do think that it was in 71 was a bad episode. The Indians were worried that whatever child that they help born that it was not to their benefit. Now we have two hostile countries in-stead of one. Except that again, for some time, it was alright, sometimes one could have played that card, but ultimately, the reality took over.

And right now, I do not think one is thinking of that option at all. Not only Khalida Zia did not do very well. Or, Haseena Wajid seems to have established herself. But I think the reality also probably in one form, or the others took over the new situation. But even then, who knows?

Read more: A Meeting on Christmas Night Dacca, 25 Dec 1962

I’m not saying that this is the end of this; after all, the Chinese are more interested in Bangladesh than they are in many other places. So we do not know what type of configuration, but the type of combination will come up in the years to come.