In November, Covid-19 claimed a very unusual and controversial life in Pakistan. Khadim Hussain Rizvi, the founder of Tehreek-e-Labaik Pakistan (TLP), died on 19th November in Lahore. He was suffering from fever and breathing difficulties – though he never got himself tested for Covid; reason could lie in the fact that in his sermons, he had claimed that Covid afflicts sinners. Despite his illness, he arrived to speak on the second day of Faizabad rally (dharna) in Islamabad organized by his party, TLP, against the French President, Emanuel Macron on the issue of Prophet (PBUH) caricatures.

During his speech, that turned out to be his last, Rizvi categorically denied that TLP protesters had ever planned to attack the French embassy – but demanded Pakistani governments (with thinly disguised references towards the country’s establishment) to become a protector of the Prophets’ respect and reminded them that Pakistan cannot survive by denying its basis – which is Islam.

The Khadim Hussain Rizvi Phenomenon

In the last few years of his life, Rizvi had aroused strong emotions for and against him. Almost two hundred thousand people attended his funeral in Lahore around Minar-e-Pakistan – though it was not an organized funeral that allows few days between death and burial. Islam emphasizes the earliest possible burial, and the crowds assembled spontaneously.

Read more: TLP Leader Khadim Hussain Rizvi passed away

All combined opposition parties of Pakistan now protesting against the government under the banner of PDM are unable to gather such a crowd on 24 hours’ notice. No doubt the governments and establishment of the country were wary of him and dealt him with caution. PM of Pakistan, Imran Khan and the country’s powerful Army Chief, Gen. Bajwa tweeted condolences for him – though both in last few years suffered utter profanities from Rizvi and had every reason to hate him.

English speaking Twitter was celebrating his death and was full of ugly words for him, despite a strong tradition across the Muslim world not to say bad words for the dead. In short Khadim Hussain Rizvi was a phenomenon.

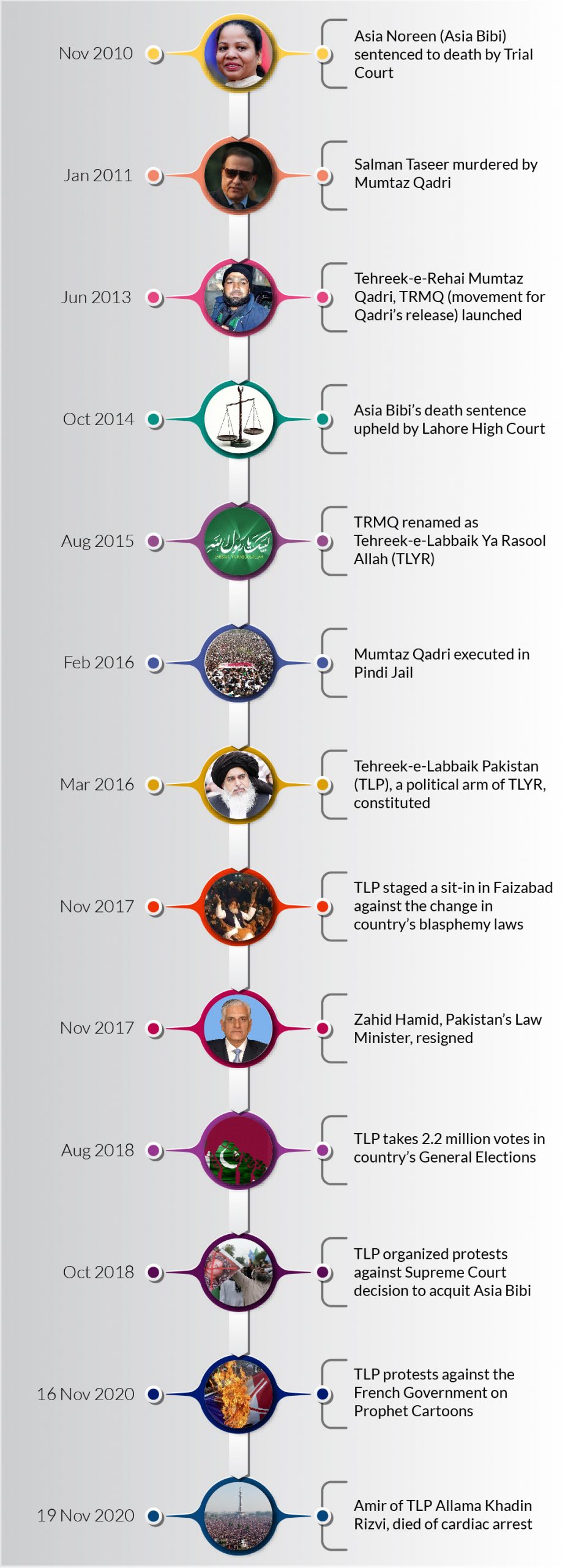

Question on all minds is what the future of TLP is after him? To answer that question, one must first grasp the nature of TLP around which the personality of late Khadim Hussain Rizvi blossomed. Rizvi had formed this party in March 2016, the very day Mumtaz Qadri, the convicted murderer of former Punjab governor Salman Taseer was buried after execution in a jail in Rawalpindi.

Read more: Pakistan reacts to demise of firebrand cleric Khadim Hussain Rizvi

This is a political front for “Tehreek Labbaik Ya Rasool Allah which literally means: “Rasool, I am here”. This religious group first appeared in Punjab as Tehreek-e-Rehai Mumtaz Qadri (movement for Mumtaz Qadri’s release) in 2013 and was later renamed the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Ya Rasool Allah (TLYR). This is the genesis of TLP that started challenging Pakistani governments and state on the streets.

But it was not a violent movement per se, its importance and fear were connected with its widespread appeal that resonated with the masses – especially in Punjab. It was seen as politically destabilizing. From an academic lens, it can be described as a backlash against globalization – as explained below.

Till the assassination of the Governor, Salman Taseer, Rizvi was an unknown, undiscovered, character serving as a junior Auqaf official in the Punjab government. Auqaf is the department that is responsible for maintaining religious sites, mosques and shrines.

He delivered Friday sermons at Lahore’s Pir Makki Masjid under Religious Affairs Department. The assassination of Taseer and arrest of Mumtaz Qadri served as the trigger that catapulted Rizvi into the phenomenon that he will be remembered for. He started justifying, in his Friday sermons, Governor’s assassination on the pretext that Taseer had termed the country’s blasphemy law as a “black law”. Auqaf Department served warning notices to him to stop his lectures.He refused and was sacked from the government job.

Read more: Lahore shuts down for funeral of Khadim Hussain Rizvi

Khadim Hussain Rizvi’s Rise as a Preacher

Rizvi’s real rise into prominence as a preacher starts after his sacking from the government job. He travelled across the country to build support for Section 295-C of the Pakistan Penal Code, which deals with blasphemy committed against Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). He also spoke out for the release of Mumtaz Qadri.

Rizvi was fluent in Punjabi, Urdu, Arabic and could say verses in Persian. He had also written books like Tayaseer Abwab-ul-Sarf, Maktba Majadia Sultania, Taleemat-e-Khadimiya and Fazail-e-Durood Shareef – mostly dealing with rituals. But it will be utterly misleading to describe him as a scholar of Islam. His peculiar religiosity and world view were a function of his socio-economic class and lack of broad-based education. He was born in 1966 in the Pindigheb area of Attock District, Punjab, that has long provided soldiers and officers to Pakistan Army.

His brother, Ameer Hussain, is a retired Junior Commissioned Officer (JCO) from Pakistan Army – who must have joined as a soldier several years ago and became a JCO after several years of service. Socio-economic class and the limiting nature of early education and exposure also explains the kind of reactionary world view he developed, and it also explains the type of religious following he later created – and that thronged to attend his funeral ignoring the raging wave of corona pandemic.

Read more: Who is Khadim Hussain Rizvi?

He was a kind of a verbal Robin Hood, a Punjabi Robin Hood against Pakistan’s English-speaking elite; a verbal warrior to his followers who adored him to the dismay of educated Pakistanis.

After Taseer’s assassination, in January 2011, it was argued by some sociologists that reaction of Punjabi ulema and maulvis is best understood not in religious fault lines but the class differences. Taseer – founder of Taseer Hadi, World Call and Daily Times – belonged to a wealthy western-educated class of Pakistanis, his father, Dr Mohammad Din Taseer, had obtained PhD from England before partition and was a noted Muslim professor in British India and close to Marxist poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz.

Taseer’s mother, Christobel George (English lady converted to Islam and called Bilqis Taseer) was the sister of Faiz’s wife, Alice Faiz. Taseer’s dismissive comments on the maulvis, on the issue of Asia Noreen (Asia Bibi) were thus seen as his class arrogance towards maulvis who are referred respectfully as “Ulema” by media and public in Pakistan – but usually come from lesser-educated sections of society.

Read more: Khadim Rizvi’s son appointed as TLP’s new Ameer: One more case of hereditary politics?

Islam entered Northern Hindustan, from 9th century onwards, via Central Asia, mostly through Persian speaking Turkish origin nobility. South Asian term “Maulana” was derived from the Turkish “Mevlana” (like Mevlana Rum, Rumi). Gradually the words “Maulvi” and “Maulana” have become interchangeable in the Indian Subcontinent as a title of respect, but Maulana was more often associated with formal qualification following study at a madrassa or Darul Uloom in the heydays of Islamic civilization when Maulanas were indeed embodiments of the world’s best broad-based education.

In post-colonial Pakistan, the word “Maulvi” has often been understood as derogatory. Taseer represented the educated classes that held “maulvi” in utter contempt. All those commenting on Taseer’s murder and the rise of TLP without understanding these nuances are wasting their time and misleading the world. This class and world view divide may also explain the equally reactionary comments from some on Twitter who unnecessarily compared Rizvi, after his death, with Hitler and Hilako Khan (grandson of Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan).

Khadim Hussain Rizvi’s Rise as a Political Opponent

Rizvi was a foul mouth preacher who uttered profanities against Ahmadis, Hindus, westernized Pakistanis and did not spare country’s top politicians, Prime Ministers and Army generals. His videos in Punjabi became popular because these were seen as entertaining and became part of the genre of “Punjabi Juggat Bazi” against country’s ruling elite – that is either seen as “westernized” or seen aligned with western values.

Read more: Will Government fulfill its latest Agreement with TLP?

His utterances, spread through YouTube, Facebook and Twitter, can easily be compared with bravado dialogues of Bollywood characters that challenge the powerful. TLP can thus be understood as a political product of the country’s socio-economic and world view fault lines. Mumtaz Qadri’s hanging may have triggered TLP’s emergence, but its roots lie deeper – and that is the challenge that Pakistani intelligentsia, politics and establishment have to grapple with.

TLP Timeline:

Rizvi had used his platform to ridicule and blast all he despised – his last lecture, on the night of 16th November in Faizabad, was a parody of country’s “Agencies”. He will be remembered for his 2017 dharna at Faizabad, Islamabad that had paralyzed the twin cities and for the November 2018 short outburst of violence across Punjab in which at least one man died. 2017 dharna was against the change in the country’s blasphemy laws, and the 2018 protests were against the supreme court judges who had set Asia Noreen (Asia Bibi) free.

The politico-religious effect

It was in the context of Asia Bibi’s release that Rizvi and other firebrands of TLP kept demanding death for judges lead by Justice Asif Saeed Khosa. In 2020 he also barged into the world of arts when he took a position against the release of film “Zindagi Tamasha” and accused noted filmmaker Sarmad Khoosat of blasphemy. Interestingly the material he considered blasphemous was at best an artistic critique of the socalled “ulema”. Despite clearance by the Senate Committee on Human Rights, the film could not be released.

Read more: We, the Hypocrites: The public trial of Sarmad S. Khoosat

However, despite creating these side issues, the central plank of the politics of TLP has remained “Respect for Prophet”. But no one in the country ever disrespects the Prophet; Muslims cannot think of disrespecting the Prophet and Muslims are the only religious group of the world that respects other Abrahamic religions like Christianity and Judaism.

The opposite is not true, since Christians and Jews do not accord the same respect to Islam or its Prophet. But this is not a national issue, Hindus, Christians and other minorities of Pakistan fully understand the local cultural nuances. Any digressions from this norm that may happen at angry moments of private disputes are far and few and don’t pose a challenge to social order.

Muslim kings that started to rule Northern Hindustan from 10th and 11th century onwards never thought of any blasphemy laws. British in 19th and 20th century first created these legal instruments – of fine and brief punishments – to discourage Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs from creating village disputes on trivial personal matters. After partition, Pakistan’s religious parties first used “Anti-Ahmadiyya Movement” and later “Blasphemy laws” to unite ultra-right vote banks and gain political importance.

Capital punishment got added to “Pakistan’s Blasphemy laws” only in 1990 when PMLN was trying to woe religious right to prove itself more Muslim than the liberal-minded PPP. Laws were subsequently misused right and left to settle personal vendettas, but no government dared to get these out of statute book. Even reform became impossible.

TLP’s importance and fear are connected with its popular appeal that resonated with the masses – especially in Punjab. It was seen as politically destabilizing. From an academic lens, it can be described as a backlash against globalization.

Musharraf government tried diluting by giving authority to deputy commissioners to ascertain facts before registration of police reports (FIRs) – and failed against a religious backlash. Since European governments and NGOs supported by them kept demanding reforms, it started to become an issue of “national assertion” versus the “West”.

Given that “blasphemy” is not a commonly occurring societal challenge inside Pakistan, TLP’s demand around which it structured its politics is thus basically a national paradox and can only be understood as a reaction against the world outside – the strength of its feelings around the Asia Bibi case testifies to that.

Asia Noreen’s fate created an international outcry – and it was the only case where the sentence was upheld by a High Court – before that government-directed bureaucracies were always able to buy reprieve at the High Court level. Salman Taseer’s murder, Mumtaz Qadri’s hanging, TLP’s rise and violence of November 2018 against the supreme court are all interconnected.

Read more: Khadim Hussain Rizvi indicted in terrorism case in Lahore

The problem now for Pakistani politics and establishment is that while TLP may not have obtained more than 2.2 million votes, in 2018 elections, but the appeal of its anti-elite feelings packaged as “religion” resonates across large sections of populations especially in the provinces of Punjab and KP.

And that explains the fear that it invokes in both the governments and the establishment. TLP sentiments can also be hijacked by external agencies and used in clandestine ways to disrupt political harmony – it may not have happened so far but is a definite possibility. In the game of political chess, the pawn may not know the hand that moves it.

Another case of Hereditary Politics

Khadim Hussain Rizvi’s position has now been taken by Saad Hussain Rizvi, his young son – whose first speech on YouTube has been watched more than half a million times in 72 hours. Given the genesis of TLP in Pakistan’s fault lines of world view, its appetite for street protests and other demands will not go away.

Read more: Pakistan reacts to demise of firebrand cleric Khadim Hussain Rizvi

Instead of dealing with TLP as a demon, or making comparisons with Hitler, as some liberals do, Pakistani governments need to focus on the issue of school and college education. An effective school education that empowers student’s capacity to learn about the world, and the diverse majestic history of the Muslim world – Seljuks, Fatimids Andalusia, Ottoman etc. and how Muslim empires interacted with their world and the minorities inside – instead of a narrow focus on 31 years of Khilafat-e-Rashida will go a long way in reforming the mindset that lies behind the movements like TLP.

Muslim predicament in the current world order and a realistic way forward for integration into a globalized world needs to be understood by the average Pakistani. Even the so-called “liberals” don’t understand it. Discussions of street protests, small events here and there and conspiracy theories – of this colonel and that general – will not serve the purpose of a nation-state of 200 million. Challenge is to address the issue of world view being imparted by school education. Herein lies the real demon.

Moeed Pirzada is Editor Global Village Space; he is also a prominent TV Anchor and a known columnist. He previously served with the Central Superior Services in Pakistan. Pirzada studied international relations at Columbia University, New York and Law at the London School of Economics, UK as a Britannia Chevening Scholar. This piece involved additional research by Sub Editor, Ahmar Hussain.