Written by Amer Zafar Durrani and Hudda Najeeb Luni

The 2022 National Security Policy (NSP) of Pakistan aspires towards improved performance on three interconnected security paradigms i.e., a) traditional security, b) economic security, and c) human security—laying emphasis on economic security and geo-economics. Geo-economics, a 20th-century concept, implies “leveraging one’s geography to maximize on economic prospects”. Parallel to efforts towards ending regional isolation, Pakistan first needs to address its core macroeconomic ills and improve its social fabric. Pakistan, the top 10 fastest growing economies during the 1960s and 1990s, is now condemned as the “Sick man” of South Asia.

Since inception Pakistan has experienced unsustainable and non-inclusive economic growth, both of which are a prerequisite for sustainable development and security. On the economic front, Pakistan consistently suffers from stagflation—low growth rate and high rate of inflation. Currently, the country is facing a surging double-digit inflation rate of 13 percent on a year-on-year basis (January 2022) which is highest than the South Asian regional average of 5.6 percent. Pakistan consistently runs a current and a trade account deficit—due to, larger than required, government and recurrent and capital expenditures, an inappropriate taxation regime, a consumption fueled economy, and an inability to appropriately export to regional and the global markets. Pakistan’s total debt and liabilities in 2021 stood at 289 billion USD, and total public debt stood at 239 billion USD—exceedingly high for a 300-400 billion economy. All these indicators will be far less severe in relative terms if only Pakistan’s economy were growing at a stable rate of 7-9 percent per annum than its present average rate of 3.7 percent.

Read more: Matiari-Lahore transmission line to boost Pakistan economy: China

Why it is important to pay attention to the economy?

The economic base of a country is a real determinant of national security expenditures, thus national security gets a larger amount with a rapidly growing size of the economic base, even at a constant or decreasing percentage share. Pakistan and South Korea make for an interesting comparison, given a similar development starting point—in 1961, both economies were below USD 4 billion, and had similar GDP/capita—below USD 100/capita, today, the South Korean economy has grown by 200 folds and is USD 1,638 Billion while Pakistan’s has grown by 14 folds to only USD 262 Billion.

Since 1960s both countries spent a fair share of GDP on defense expenditures to cushion against the existential threat they faced from their immediate neighbors. In the sixties and seventies South Korea spent almost 7 to 5percent of its GDP on defense, whereas Pakistan also spent 4 to 7 percent at the same time, however, in 2020 South Korea spent only2.8percent of its GDP (60 billion dollars) on defense whereas Pakistan spent 4 percent (10 billion dollars).

Pakistan’s poor socioeconomic rate of development is primarily a result of its low economic productivity, i.e., poor returns on labor, capital, and other inputs, low technological advancement—particularly low economic complexity—and inability to develop trade with local and regional markets. Pakistan’s labor productivity has been declining, from an average 4.2pc (during 1990s) to 1.3pc (during 2000-15), however since 2007 it has been stagnant at 1 percent. Contrary to the growing trend in India, where the labor productivity increased to 5 percent (during 2000-10).

ECI Ranks Pakistan on 100th and South Korea on 5th rank out of 146 countries

Pakistan’s major exports in 2020 comprised of House Linen (13 percent) and Rice (9 percent), whereas South Korea mainly exported Integrated circuits (15 percent) and cars (7 percent). Exports earnings and reserves accumulation are a natural outcome of specialized and knowledge-intensive economies that thrive on the exports of innovative products. Deteriorating productive capacity due to lack of investment in human capital has left us far unprepared to compete with the specialized and complex regional and global export market.

There has been a systemic exclusion of masses from the development of minds (education and health) and means (economic opportunities) primarily due to (a) the Pakistani state’s inability to move away from its inherited colonial extractive institutions and laws, (b) a burgeoning population, (c) a lack of visionary leadership and consensus to develop a new social and economic order, and (d) isolationist regional foreign policies (befriending enemy’s enemies).

A few elites—social and economic, or both—captured the country’s resources. The social safety net programs, Ehsaas program, Benazir Income Support program (BISP), and Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund (PPAF), have successfully hoodwinked the poor masses into believing in an apparently emerging benevolent state. Human security never had any mass appeal—with the elites parking wealth and allegiances outside the borders of Pakistan. Pakistan’s human development indicators lag from the rest of the world—ranking 154th on the Human Development Index. Without investing in human capital Pakistan cannot build a resilient economy which thrives on its people and their productive capacities.

Read more: Pakistan economy to suffer if Afghan peace talks fail

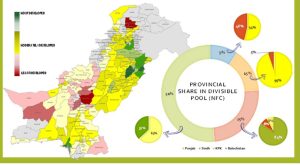

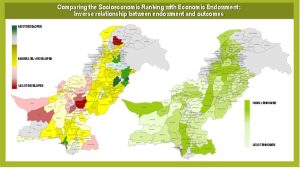

Internal fragility, ineffective fiscal allocations, and inefficient expenditure, topped by the inability to develop local economic endowments, primarily due to the legacy extractive institutions has kept equitable socioeconomic development of Pakistani people at bay! Pakistan couldn’t reap the benefits of its abundant resources due to archaic and inefficient institutional structure. Institutions are the ‘rules of the game.’They structure incentives in human exchange, whether political, social, or economic.

Inclusive institutions are the drivers of the economic strength of the Internal fragility, ineffective fiscal allocations, and inefficient expenditure, topped by the inability to develop local economic endowments, primarily due to the legacy extractive institutions has kept equitable socioeconomic development of Pakistani people at bay! Pakistan couldn’t reap the benefits of its abundant resources due to an archaic and inefficient institutional structure. Institutions are the ‘rules of the game.’They structure incentives in human exchange, whether political, social, or economic.

Inclusive institutions are the drivers of the economic strength of the nations

Government regulations, labor laws, tax laws, judicial efficiency, and strength of other related institutions require modernizing and, in some cases, absolute extinction to address the obstacles created in the way of development of people and commerce and to counter fragility by improving provision of universal internal security and justice. Liberty originates from a delicate balance of power between state and society.

Between the “Despotic Leviathan” (all-powerful state) and “Absent Leviathan” (state-less society)there exists a narrow corridor of liberty in which individuals flourish and prosper. Pakistan is an example of “Paper Leviathan” a special blend of Despotic with the Absent Leviathanwhere the state remains neutral and ineffective because those in power do not wish for the people to mobilize.

Persistent internal fragility, conflict, and violence within an unstable and unfriendly neighborhood have been used as an excuse to close borders, killing trade and economic opportunity, throttling the economy. Closed borders are insecure borders. Open borders are secure borders—they can be controlled. Evading closed borders has been the root cause of insecurity, smuggling, and financial losses to Pakistan. Closed borders have also resulted in the isolation of minds and cultures and in impeding the free trade of goods and services. Pakistan must divorce its “Cold war” thinking patterns and resort to opening borders for free movement of people, goods, and data.

Opening borders also means lowering trade tariffs

Pakistan exercises a strict tariff regime. South Asian (SA) countries have the highest, almost 12 percent applied tariff rates (simple average) and central Asian (CA) countries have between 7-3 percent, while European Union (EU) countries have almost 3 percent value. EU emerged as a model of regional integration post-WWII, where economies were crumbling under hyperinflation in the aftermath of the war and in 1923 Germany was one of the heavily indebted countries in the world and at that time the worth of 42 billion Marks was equal to one American Cent. Fast-forward, post the formation of the coal and steel community and subsequently with the emergence of EU as a unified economic bloc, in 2020, EU’s share in the world’s GDP was 18 percent, whereas SA’s share was less than 4 percent and CA’s less than 0.2 percent.

Pakistan must improve its bilateral ties with all its neighboring counterparts, regional stability is at the heart of regional connectivity and economic integration.NSP reinforces stability in Afghanistan and bilateral cooperation with China for CPEC-related and other projects as its important regional prospects of Pakistan. It stresses upon Pakistan’s economic ties and mutual cooperation with the GCC. NSP also looks for strengthening ‘bilateral economic linkages and defense cooperation’ with Turkey particularly, and West Asia in general. NSPidentifies just and peaceful resolution of Kashmir dispute as a core determinant for improving relations with India—hopefully waiting for the resolution will not deter resumption of open economic-trade relations.

Read more: Food security in danger: Pakistan Economy Watch

Pakistan’s geostrategic construct places it as a part of a wider Central Asian Region, nestled amongst the fastest growing economies, and a pivotal route for many regional players such as China, India, Russia, Iran, and Central Asian countries such as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Pakistan is a melting point of Central Asia (CA), South Caucuses (SC), South Asian (SA), region. This proximity to greater central Asia presents an opportunity to rethink regional integration via a rather natural “Moscow-Karachi” alignment and trade route—for goods, people, and data.

Since post-WWII, Pakistan, and its neighborhood, emerged poorly integrated. Poor connectivity and inadequate infrastructure, cross border conflicts, concerns about security, missing transport links, inappropriate trade and transit agreements, and poor trade and transport facilitation measures are curtailing its, and the region’s, economic growth, and shared prosperity—and thereby its security. Cross-border trade and transit facilitation improves the growth and levitates the income of countries.

SA and CA countries have various overlapping regional cooperation programs and trade blocs such as, SAARC, BIMSTEC, ECO, SPECA, CAREC and SASEC, but none work—being simply talk-shops and a means for officials to go on junkets! The Logistics Performance Index (LPI) compares countries for various indicators and provides information on “logistics infrastructure, service provision and cross-border trade facilitation”. In 2018, the SA countries had anaverage LPIranking of 155, CA and SC countries were at 83, and the high Income countries were at 28—with the lower number showing how easily goods move across borders.

Pakistan continues to be a regionally isolated country even though geographically it is a natural corridor for transit trade. It shares a 7,257 kilometer border with four neighboring countries, India (to its east), Iran.

Pakistan continues to be a regionally isolated country even though geographically it is a natural corridor for transit trade. It shares a 7,257-kilometer border with four neighboring countries, India (to its east), Iran (to its west), Afghanistan (to its west), and China (to its north), with a 990 km coastline leading from the Arabian sea to the Indian ocean—some of the most trafficked waterways.

Ending Pakistan’s regional isolation should command center-stage in any discussion on national security and especially in the context of the recent national discourse around geo-economics. Geography plays a central part in economic security and is not tradeable! Countries, unlike its citizens, cannot trade up geographically! People can migrate in search of better economic futures. Countries are stuck in their geographic location—not realizing that and reaching out over the heads of neighbors to find distant friends is neither good economics nor a good security strategy.

Pakistan is fortunate that the world’s economic center of gravity is shifting back to our region with the world’s two largest economies and markets located as our immediate neighbors. Ending Pakistan’s regional isolation underpinning its national security imperative we should therefore be asking some of the following questions. Will the center of gravity of the global leadership also shift to this region? How will the 20th century Bretton Woods construct be affected? Will the, so called, “rule based global order”.

Pakistan is fortunate that the world’s economic center of gravity is shifting back to our region with the world’s two largest economies and markets located as our immediate neighbors. Ending Pakistan’s regional isolation underpinning its national security imperative we should therefore be asking some of the following questions. Will the center of gravity of the global leadership also shift to this region?

Read more: Pakistan Economy: History and Required Reforms

How will the 20th century Bretton Woods construct be affected?

Will the, so-called, “rule-based global order” survive the “Confucian” constructs? Will the “greenback” still persevere as the trade settlement currency of choice? What will be the shape and role of our immediate neighborhood in 2050—just a quarter of a century from now? These questions are even more relevant in the face of an emerging need for a new global security, regulatory, economic, and social architecture.

Pakistan has traditionally been a follower and adopter of ideas and orders—be they relating to economics, society, or security. Time has come for Pakistan to emerge as the creator and purveyor of ideas and orders for the emerging global realities—under which we promote the idea of moving to ‘bold’ rather than the existing ‘timid’ economic approaches—more on this in a subsequent article. To do this, many threads need to be woven and then, interwoven. For achieving the three pillars of the NSP, we list the key ones as follows.

- Combining foreign policy and foreign-aid-architecture under one institution and divorcing it from the fiscal bureaucracy—and subserving all foreign debt attainment to parliamentary accountability.

- Utilizing local thought centers and academia for inventing and innovating economic and social constructs for the 21st century.

- Unlocking local capital—away from sprawling real-estate—and resources towards productive investments and towards creating new million people dense cities.

- Focusing on technological advancement by letting the current defense-centered technology island be permeated by and accessible to the private sector—the panacea is not being the back office for IT services.

- Improving connectivity with Central Asia and the South Caucuses and eventually Russia, Iran, Turkey, and Africa, by leveraging CPEC and BRI—once this happens, India and its east will come willingly to the negotiating table.

- Rewriting the destiny of “Wakhan Strip”and benefit from the EurAsEC Customs Union at Pakistan border, and “shrug-off” Afghan burden.

Our immediate ability to act on these while improving internal governance and the voice of the citizens will provide the ultimate human and national security by ending our regional isolation. Each of the topics explored in this article deserves more in-depth discussion and the authors hope to carry this forward with the help of our readers.

Read more: How is FBR hurting Pakistan economy?

Written by Amer Zafar Durrani and Hudda Najeeb Luni

Mr Durrani is an acknowledged development expert who is presently involved in renewable energy and community-driven development; transport and logistics, trade facilitation, and connectivity. He has worked with World Bank Group for 18 years. He also launched IdeaGist Pakistan- bringing the world’s largest virtual incubator to Pakistan’s growing incubation and innovation entrepreneurial ecosystem. Currently, Amer Zafar Durrani is the President of Reenergia and Paidartwanai.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Village Space.