The Economic Advisory Group (EAG), an independent group comprising individuals from academia, policy, and the private sector, presents a vision for economic transformation that focuses on understanding key factors which have prevented this from happening in the case of Pakistan.

It draws from the experience of other emerging economies and leading economic research on how countries have successfully transformed their economies by letting their productive structures adapt and evolve over time.

The recommended policy actions laid out in EAG’s recent publication, New Vision for Economic Transformation, are a significant departure from the traditional focus on achieving growth by reinforcing existing structures of the economy. While such traditional approaches did deliver many episodes of growth spurts, these always proved to be short-lived, often leading to the build-up of large imbalances and, ultimately, crises.

Read more: Regional Connectivity: Vital Element of Economic and National Security

A key requirement for transformation is that economic resources must be allowed to move from less productive to more productive activities. In a market economy, this critically depends on whether the incentive structure is allowed to evolve such that returns from investing in more productive activities are indeed higher than those from less productive activities.

Countries become what they make

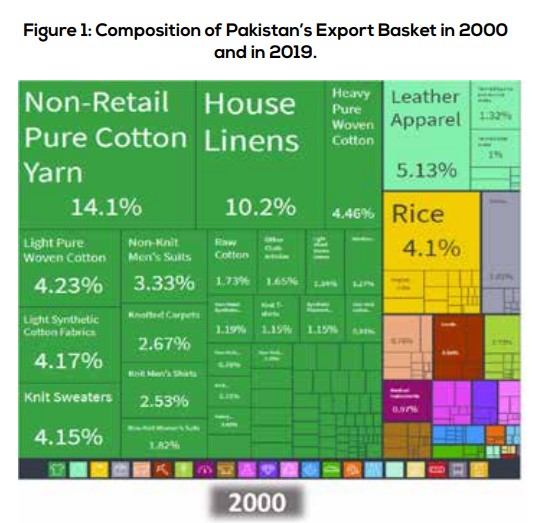

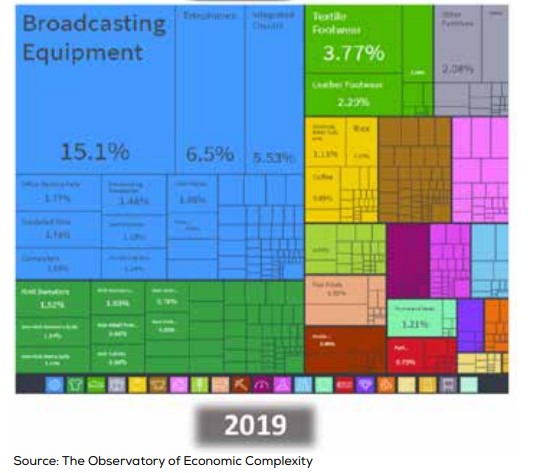

Data shows that the structure of Pakistan’s economy has remained ossified over the past several decades. The data includes exports of goods and is taken from the Observatory of Economic Complexity. The lack of economic transformation which the country has experienced since 2000 stands out.

In 2019, Pakistan’s export basket continued to be dominated by similar low value-added manufactured goods and primary products, as in 2000. Going even further back in time presents a similar picture.

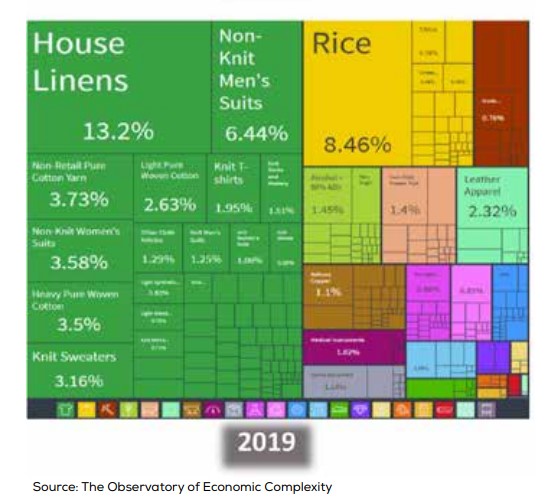

In contrast, similar data for Vietnam shows it has successfully transformed its economy towards producing high value-added manufacturing goods. Specifically, Vietnam’s production structure has moved away from low value-added products towards high and moderately sophisticated sectors such as electronics, chemicals, value-added textiles, and tourism. Such transformation is not limited to Vietnam alone but extends to other emerging economies, including Thailand, the Philippines, and China, amongst others.

Lack of capabilities

Apart from failing to transform the sectoral makeup of its production structure, Pakistan has also fallen behind in gaining the capabilities necessary for producing high value-added products within existing sectors. For example, while Pakistan added 21 new products in its export basket since 2003, these only contributed $2 per capita to the value of its exports.

In contrast, Thailand and Vietnam added 34 and 48 new products, contributing $213 and $1,020 per capita to the value of their exports, respectively. Pakistan’s inability to produce high value-added products is reflected in its ranking on the Economic Complexity Index (ECI), which is based on countries’ relative sophistication levels; and reflects locally available capabilities at any point in time.

Read more: EAG welcomes focus on economy, cautions on overstretch of NSP

Countries exporting a large variety of products that few other countries can make are ranked higher on the ECI than those making a narrow range of products that many other countries also make. The graph above shows that not only is Pakistan’s ranking low at 99 out of 133 countries, but the economy has become relatively less sophisticated, declining five places in ranking over the last decade. In contrast, Thailand’s (22) and Vietnam’s (52) ECI ranking improved by 9 and 11 places, respectively.

Pakistan’s lack of sophistication is reflected in its export basket, which is made up of less complex products and has remained so for decades. This is worrisome as the level of complexity is a strong predictor of a country’s growth potential. Hausmann and Hidalgo (2010) show that the sophistication of products made by countries matters more for long-term prosperity than simply the value extracted from them.

In the long run, the economic growth of countries is driven by the complexity of their respective economies. The relative positioning of countries on the index also seems to explain much of the variation in income levels across countries. By the same token, where there is a deviation from the relationship between income and the corresponding level of complexity, it predicts the country’s future growth potential.

For example, Vietnam, which is ranked 41 positions higher than Kazakhstan, despite having less than a third of the latter’s per capita income, is expected to grow significantly faster than the mineral-rich exporter. Effectively, the complexity of economies not only infers the actual level of income but also their latent potential.

What is needed for transformation?

The economist Franklin Fisher’s statement that “In dealing with actual economies, the barriers (for resources to move) may be more important than the frontier” underpins much of EAG recommendations to enable much-needed transformation. The independent think tank recommends the need to eliminate rent-seeking behavior that has prevented economic resources from getting reallocated from less to more productive endeavors.

Businesses that are unable to compete internationally through lack of innovation or inability to gain sufficient economies of scale and only survive through state subsidies or protection should be allowed to discontinue. This would encourage economic resources to move towards more productive businesses that can compete globally.

Read more: On National Security Policy of Pakistan

Elimination of rent-dependent activities would provide the impetus for a transformation towards the production of more value-added goods and a sophisticated economy much like China, India, Thailand, and Vietnam have succeeded in creating. Without doing so, Pakistan cannot prosper.

Barriers to transformation in Pakistan

EAG contends that economic resources in Pakistan have failed to move towards the production of more complex goods since policy interventions have worked towards ensuring that the returns from engaging in the production of less complex goods continue to remain high.

As a result, there is no incentive for resources to move towards more productive endeavors. EAG contends that the key reason why Pakistan has not undergone a similar transformation as, let’s say, Vietnam is because excessive protection and lack of structural reforms have prevented economic resources from getting reallocated to more productive endeavors.

Rethinking Policy

While the policy areas identified and suggestions put forward by EAG are diverse, they are all geared towards putting in place an incentive structure that transforms Pakistan’s economy into an economy with a high degree of economic complexity, and hence greater relevance and potency in the context of the 21st-century globalized world.

Specific recommendation under four themes

- Revisiting pricing regimes that currently govern agriculture and commodities sectors.

- Revamping of the education system with the aim to introduce and mainstream pathways for vocational training at the level of higher and postsecondary education.

- Reduction in tariff and non-tariff trade restrictions and greater integration with regional trade blocs; and, finally.

- Rethinking industrial policy with special emphasis on moving away from picking winners to rewarding innovators, improving land-use within cities, and simplification of the tax code.

Read more: Is a bloated bureaucracy responsible for Pakistan’s fiscal deficit?

EAG argues that it is only through these policies that the economy can progress beyond its ossified structure. A change of mindset and putting in place an incentive structure that is aimed at building capabilities and continuously allocating resources from less productive to more productive activities is imperative for transformation.

Javed Hassan has worked in senior executive positions both in the profit and non-profit sector in Pakistan and internationally. He is an investment banker by training. He Tweets @ javedhassan

The views expressed by the writers do not necessarily represent Global Village Space’s editorial policy