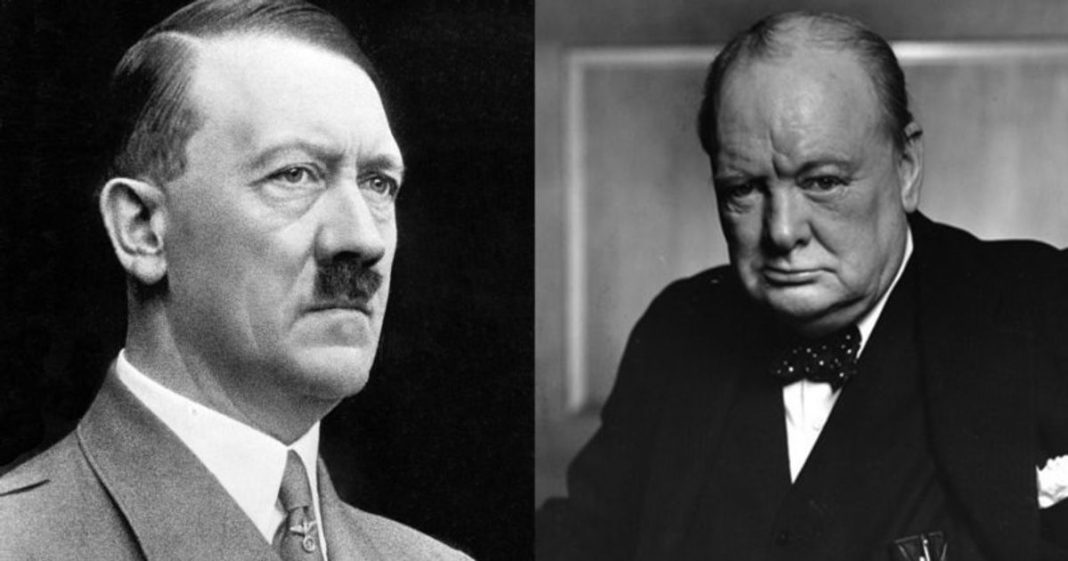

Early this century Winston Churchill was voted “the greatest Briton of all time” in a nationwide British poll, which attracted more than a million votes, as he finished ahead of figures like the naturalist Charles Darwin.

It is little known, however, that Churchill had favorably viewed European fascism during the 1920s and 1930s; that is before the expansionist policies of the fascist dictators began to affect British interests.

In October 1937, almost five years into Adolf Hitler’s dictatorship in Germany, Churchill wrote in the Evening Standard about, “The story of that struggle” regarding Hitler’s rise to power which “cannot be read without admiration for the courage, the perseverance, and the vital force which enabled him to challenge, defy, conciliate or overcome, all the authority or resistances which barred his path.”

Read more: Op-ed: German expansionism and slave labour during World War One

Churchill refused to criticise either Hitler’s suppression of those who opposed him, nor his erecting of concentration camps, which by 1934 were under the direct control of the SS. Churchill continued that “history is replete with examples of men who have risen to power by employing stern, grim and even frightful methods” but “when their life is revealed as a whole, have been regarded as great figures whose lives have enriched the story of mankind. So may it be with Hitler”.

Less than four years later, by June of 1941, Churchill was calling Hitler over the radio “a monster of wickedness, insatiable in his lust for blood and plunder”, as Hitler was directly challenging Britain’s diminishing empire and her financial concerns.

Churchill admired fascist leaders

Through the 1930s Churchill had wanted to accommodate Hitler while forming a solid alliance between Britain, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, which he hoped would deter the Third Reich from advancing westwards. Churchill suggested as much in a May 1936 letter to Violet Bonham-Carter, daughter of former British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. Churchill believed there was a good chance these policies would convince the Führer to, instead, turn his military might to the east: against the Soviet Union, a state which Churchill disliked and distrusted considerably more than Nazi Germany; while he professed that “Britain and France would maintain a heavily-armed neutrality”.

The English historian John Simkin wrote, “Churchill believed that the right strategy was to try and encourage Adolf Hitler to order the invasion of the Soviet Union… He expected that Hitler would turn eastwards and attack the Soviet Union, and he proposed that Britain should stand aside while his old enemy Bolshevism was destroyed.” Churchill was one of the few British politicians who had read Hitler’s 1925 book ‘Mein Kampf’, in which the Nazi leader outlined bluntly his aim to conquer vast territories in the east.

Read more: US-British policy of appeasing Mussolini’s rule

Churchill was an admirer of fascist leaders like Benito Mussolini, whom he praised for having “thought of nothing but the lasting good” regarding the Italian people. While visiting Rome in January 1927 Churchill wrote to his wife, “This country gives the impression of discipline, order, goodwill, smiling faces. A happy strict school… The Fascists have been saluting in their impressive manner all over the place.”

‘a born leader of men’

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), Churchill’s support for fascism extended to General Franco’s forces, and he was firmly against the left-leaning Republican government. Churchill denounced the Republicans as “a poverty-stricken and backward proletariat” that was resisting Franco’s “patriotic, religious and bourgeois forces” who were “marching to re-establish order by setting up a military dictatorship”.

David Lloyd George, a liberal and British prime minister from 1916 to 1922 felt it necessary to visit Nazi Germany in September 1936 to see Hitler. Lloyd George subsequently wrote about his meeting with the dictator in the Daily Express, and he enthused about Hitler being “a national hero who has saved his country from despondency and degradation” while he called him “the George Washington of Germany” and “a born leader of men”.

Read more: Battle of France: Wehrmacht advances through the Ardennes

Admiration for Hitler even came through the British Labour Party, with plaudits pouring forth from George Lansbury, the Labour leader from 1932 to 1935. Like Lloyd George, Lansbury thought it apt to go and see Hitler in the flesh, which he did in April 1937. Lansbury said later, “I think history will regard Hitler as one of the great men of our time” and it was “sheer nonsensical folly” to suggest that he wanted a European war.

The Western corporate world had been enthralled at the investment potential European fascism presented, with its destruction of leftist parties, labor-power and trade unions. British and American businessmen flocked at first to Mussolini’s Italy from the early 1920s, a regime that the Western powers would continue supporting, until the commencement of the war.

A gift of $4 million from the Bank of England

The Nazis wiped out the democratic threat in Germany, creating what was viewed as a perfect environment for big business to blossom in. Warm ties were developed between the UK’s Conservative-dominated governments and the Hitler dictatorship; particularly through the formation of Anglo-German commercial, industrial, and financial relations. In the face of popular pressures in Europe, close links to Hitler’s regime allowed the British established a strategy of self-preservation.

On 4 July 1934, Britain’s government and the Third Reich signed the Anglo-German Trade Agreement, regarded as a cornerstone of British policy with the Nazis. Under this deal, the Germans were allowed to accumulate a considerable trade surplus with London – ensuring that Berlin could purchase commodities that would assist in building up its war machine, including the acquisition of mineral resources like rubber and copper, critical to the war industry.

Read more: How Germany restored civilian supremacy: Ludendorff and Kapp Putsch

In early December 1934 the influential governor of the Bank of England, Montagu Norman, advanced Hitler a loan of around $4 million to “facilitate the mobilization of German commercial credits.” This was a nice gift, which sent out another message of British support. The following year, 1935, the Anglo-German Fellowship was founded, through which large British corporations partook, like Dunlop Rubber, Unilever, and Price Waterhouse. The Anglo-German Fellowship was an elitist organization sympathetic to Nazism. Several British MPs, mostly Conservatives, joined this society such as the pro-Nazi Thomas Moore; among its members too was the aforementioned Montagu Norman, Bank of England governor, and Frank Cyril Tiarks, a director at the Bank of England. The Anglo-German Fellowship was forced to dissolve at the outbreak of war.

Trading with the Nazis

On 18 June 1935 the UK government, under its new Conservative prime minister Stanley Baldwin, concluded the Anglo-German Naval Agreement. For the time being, this ensured that Britain would retain a much larger navy than the Germans. US-born author Guido Giacomo Preparata, who has studied US-British connections to Hitler’s regime, wrote that with the payment from the Bank of England and the naval agreement secured, “Hitler won from Britain no less than her official and financial military support. The Führer was exultant.”

One of Britain’s foremost arms manufacturers, Vickers-Armstrong, was selling heavy weaponry to Nazi Germany. Herbert Lawrence, chairman of Vickers-Armstrong and a heavily decorated English general, was asked in 1934 to give an assurance that his company was not covertly helping to re-arm the Germans. General Lawrence failed to assuage fears by replying, “I cannot give you assurance in definite terms, but I can tell you that nothing is done without the complete sanction and approval of our own government”.

At the end of the 1930s, with Hitler set to initiate another European war, Britain’s principal trading partner was Nazi Germany. British investment with the Germans significantly rose from 1933, an indication that corporations fare best where the democratic threat is least. This may explain why Conservative governments, usually supportive of corporate investment, had persisted in appeasing Hitler for so long, through fear of losing their most lucrative client.

Read more: Orchestrating a Greater Gemania; Ludendorff’s expansionist dreams

Churchill was undoubtedly aware of the British-Nazi business relations, and he had been an advocate of appeasement for years. In April 1936, with Hitler’s dictatorship consolidated, Churchill requested that the League of Nations invite Nazi Germany “to state her grievances and her legitimate aspirations” so that “justice may be done and peace preserved”.

This statement came a month after Hitler had invaded the demilitarised Rhineland, in March 1936, a stark violation of the Treaty of Versailles, unjust and all that it was. Shortly afterward, writing in an article in the Evening Standard, Churchill praised France for not “retaliating with the force of arms, as the previous generation would have”, after the Wehrmacht had marched through the Rhineland without a glove laid on it. The Nazis would have been dealt a serious blow, had France’s much larger army reacted with force, but the French government’s response was timid. This did not seem to bother Churchill, however.

US support to the Nazi’s

Prime minister Baldwin gave a silent nod of approval to Hitler’s march on the Rhineland. London informed Paris that they would not back them militarily over an issue of no concern to them. The British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden said, “Hitler was only going into his own back garden”, an irresponsible attitude that dismayed France. Baldwin’s successor as British leader, Neville Chamberlain, another Conservative, would in the autumn of 1938 willingly consent to the Munich Agreement – or Munich Betrayal – which dismembered Czechoslovakia and further strengthened the Nazi position in central Europe. Chamberlain thought the prospect of conflict with Germany unnecessary over “a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing”.

US President Franklin Roosevelt backed the Conservatives’ appeasement of Hitler. His close adviser Sumner Welles said that the 1938 Munich Agreement provided an opportunity to establish “a new world order based upon justice and upon law”.

As with their British counterparts, American corporate leaders invested large sums in the Third Reich. US Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox remarked that, in 1934 and 1935, Hitler received hundreds of state-of-the-art aircraft engines from America. Preceding this in 1933 the US firm, United Aircraft and Transport Corporation, reportedly signed a secret deal with German airplane manufacturer, Junkers, through which $1,775,000 worth of aircraft engines and rifles were sent to Nazi Germany. This US arms deal with Junkers was highlighted on 14 August 1947, by Krasnaya Zvezda, the official newspaper of the Soviet Ministry of Defence, whose report seems plausible.

Read more: Untargeted aerial bombing of Germany delayed Nazi defeat

Junkers would construct such military aircraft as the Junkers Ju 88, one of the Luftwaffe’s key fighter planes – while Junkers also built the feared Stuka dive-bomber, the design of which was made possible “with techniques learnt in Detroit”, as Preparata wrote, a senior lecturer in political economy and social sciences.

On 16 March 1935, the day that the Wehrmacht was formally established, Hitler announced that he was introducing conscription, and bolstering the size of his land forces to over half a million men. Nazi Germany was now publicly rearming, though in secret for months she had been gradually augmenting her fighting power, with assistance coming from the US and British centres of power. In July 1934, the Conservative leader Baldwin had said of Germany in the House of Commons, “she has every argument in her favour, from her defenceless position in the air, to make herself secure.”

Shane Quinn has contributed on a regular basis to Global Research for almost two years and has had articles published with American news outlets People’s World and MintPress News, Morning Star in Britain, and Venezuela’s Orinoco Tribune. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Global Village Space’s editorial policy.