Though not extending to aggression, US president Dwight D. Eisenhower (in office 1953-1961) instituted and supported the sometimes brutal methods of the Republic of Vietnam, more commonly known as South Vietnam, a state officially founded in October 1955 – pending unification of Vietnam on the basis of free elections, which were meant to be held in 1956.

The Eisenhower administration regarded the 1954 Geneva agreements as a “disaster” which stipulated, in effect, to hand Vietnam over to the Vietnamese. Instead, Eisenhower’s government quickly established the Ngo Dinh Diem dictatorship in South Vietnam, so as to thwart the perceived threat to US hegemony in south-east Asia and beyond.

The American author and historian, Noam Chomsky, wrote that this US-backed regime had, by 1961, “already taken perhaps 75,000 lives in the southern sector of Vietnam since Washington took over the war directly in 1954.

Read More: China’s programs in Tibet: Mao Zedong’s legacy

But the 1954-1961 crimes were of a different order: they belong to the category of crimes that Washington conducts routinely, either directly or through its agents, in its various terror states. In the fall and winter of 1961-1962, Kennedy added the war crime of aggression to the already sordid record, also raising the attack to new heights”.

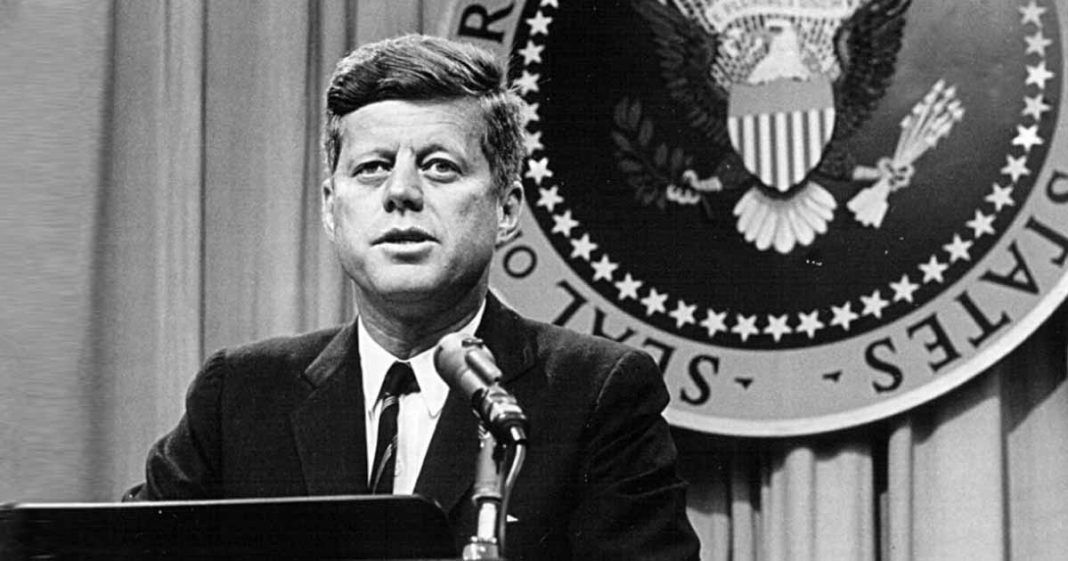

On 11 October 1961 Eisenhower’s successor, John F. Kennedy, ordered the dispatchment of a US Air Force squadron “Farmgate” to South Vietnam, consisting of 12 warplanes equipped specifically for counterinsurgency attacks – and which were soon authorised “to fly coordinated missions with Vietnamese personnel in support of Vietnamese ground forces”. Under Eisenhower, US soldiers in Vietnam remained in a “strictly advisory” role, not actually participating in raids. This status altered within the first year of Kennedy’s tenure, from terror to aggression.

Kennedy’s go ahead to using US forces in South Vietnam

On 22 November 1961, Kennedy sanctioned the use of US forces “in a sharply increased effort to avoid a further deterioration of the situation” in South Vietnam. It included “increased airlift to the GVN [South Vietnamese regime] in the form of helicopters, light aviation and transport aircraft”.

This equipment, along with the arrival of US armed force members to South Vietnam, would partake in “aerial reconnaissance, instruction in and execution of air-ground support and special intelligence”. Among the military units were three US Army Helicopter Companies, a Troop Carrier Squadron with 32 planes, fighter aircraft, a Reconnaissance Unit, and six C-123 transport planes equipped for defoliation.

Less than two weeks before, on 11 November 1961 the US National Security Council (NSC) under president Kennedy had ordered the use of “Aircraft, personnel, and chemical defoliants to kill Viet Cong food crops and defoliate selected border and jungle areas”. On 27 November 1961, it was reported that “spraying equipment had been installed on Vietnamese H-34 helicopters, and is ready for use against food crops”.

Read More: Pearl Harbor: what convinced the Japanese military, that it was ‘now or never’?

Three weeks later the US Defense Secretary, Robert McNamara, authorised newly-based US warplanes in South Vietnam to begin attacking locals, who were resisting the assaults of the US-imposed dictatorship. By January 1962 further US military hardware had arrived in South Vietnam, such as advanced helicopters, along with providing tactical air support.

Chomsky observed that the above actions by the Kennedy administration “were the first steps in engaging US forces directly in bombing and other combat missions in South Vietnam from 1962, along with sabotage missions in the North. These 1961-1962 actions laid the groundwork for the huge expansion of the war in later years, with its awesome toll”.

McNamara: Taking charge of the war in Vietnam

JFK put the hawkish McNamara in charge of running the war in Vietnam, despite him having scant experience of front line fighting. McNamara was more acquainted with office work, analysing spreadsheets or graphs. From 1946, he had worked in a civilian position for many years with the Ford Motor Company.

Kennedy was inaugurated as president on 20 January 1961. Over the next year and a half, US soldier numbers in South Vietnam increased sixfold, from about 900 on 31 December 1960, to 5,576 by 30 June 1962. The figures then doubled over the next six months, to 11,300 on 31 December 1962. In the early winter of 1963, at the time of Kennedy’s death, there were around 16,000 US military personnel in South Vietnam. During the Kennedy presidency, US troop levels on Vietnamese soil increased almost 20 times over from the end of Eisenhower’s tenure.

In July 1962, Defense Secretary McNamara stressed that US plans relating to Vietnam should stick to “a conservative view”, in that withdrawal of American forces “would take three years, instead of one, that is, by the latter part of 1965”, in the event that victory was obtained by then. This schedule would have taken Kennedy into his second term as president, providing of course that he won re-election.

Read More: Battle of France: Wehrmacht advances through the Ardennes

McNamara was Kennedy’s right-hand man, we can note – and the late 1965 timetable, regarding US involvement in Vietnam, dispels the assertions that JFK was planning to imminently withdraw US forces from Vietnam.

General Paul Harkins, himself stationed in South Vietnam, elaborated in his Comprehensive Plan of January 1963 that, “the phase-out of the US special military assistance is envisioned as generally occurring during the period July 1965-June 1966”.

Moreover, by mid-1962 US “intelligence and sabotage forays” into Ho Chi Minh’s communist North Vietnam had also commenced, according to JFK’s National Security Adviser, McGeorge Bundy. Entering 1963 the US war strategy outlined in January of that year was, as Chomsky noted, “in an atmosphere of great optimism, the military initiatives for withdrawal went hand-in-hand with plans for escalation of the war within South Vietnam, and possibly intensified operations against North Vietnam”. The reality on the ground bears proof of this.

By the summer of 1962 and through 1963, CIA activities in Vietnam were increasing. The CIA partook “in joint clandestine operations” with the South Vietnamese armed forces against North Vietnam; CIA actions in Vietnam were recognised on 11 December 1963 by US National Security Staff member Michael Forrestal.

Examining the views of military commanders vis-vis waging war in Vietnam

It can be important to examine the views of top level American military commanders, relating to the prospect of waging war in Vietnam. In April 1961, General Douglas MacArthur informed president Kennedy that it would be a “mistake” to fight at all in Asia, and that “our line should be Japan, Formosa and the Philippines”. In July 1961, MacArthur firmly repeated this stance during a three hour long discussion in the White House with JFK, but his advice was ignored.

MacArthur felt that “the domino theory was ridiculous in a nuclear age”, which purports that one country after another would succumb to communism without US intervention. Kennedy is on record as promoting the domino theory.

MacArthur’s successor as the US Army Chief of Staff, General Matthew Ridgway, expressed similar sentiments to MacArthur. In 1956, Ridgway wrote that limited US involvement in Vietnam had an “ominous ring”, which he suspected would result in escalation. He recalled the US Air Force attacks on North Korea in the early 1950s, and found it “incredible… that we were on the verge of making that same tragic error”, which is what president Kennedy would proceed to do. Ridgway later “passionately opposed intervention in Vietnam”, the military historian Robert Buzzanco acknowledged.

Read More: World War II, US military destroyed 66 Japanese cities

General J. Lawton Collins, another experienced US military man, likewise warned about armed intervention in Vietnam and surrounding regions. Collins said that he did not “know of a single senior commander that was in favour of fighting on the land mass of Asia”.

Meanwhile, in February 1962 JFK’s invasion of Vietnam was undeniable. By that month, US Air Force planes “had already flown hundreds of missions”, according to John Newman, the author and retired US major, who cited an army history.

In just one week during May 1962, Vietnamese Air Force and US helicopter units flew about 350 sorties together, including offensives and airlifts. By contrast to the military commanders, the NSC civilian leadership, knowing less about war, favoured increasing the US armed presence in Vietnam.

Throughout 1962, the second year of Kennedy’s term, the “main emphasis” for Washington was “on the military effort” in South Vietnam, as deliberated on by Arthur Schlesinger, JFK’s close consultant.

Chomsky wrote that, “By 1962, Kennedy’s war had far surpassed the French war at its peak in helicopters and aerial fire power… Kennedy’s aggression was no secret. In March 1962, US officials announced publicly that US pilots were engaged in combat missions (bombing and strafing).

JFK was on the cusp of withdrawing forces from Vietnam

Through 1962, US troops were using HU-1A helicopters against South Vietnamese guerrillas. As an offensive weapon, these helicopters contained more firepower than any World War II fighter aircraft. Contrary to the long established myth that JFK, before his assassination (on 22 November 1963), was on the cusp of withdrawing US forces from Vietnam, the opposite is in fact the case. On 17 July 1963, Kennedy said that if US personnel were sent back home it “would mean a collapse not only of South Vietnam, but Southeast Asia. So we are going to stay there”.

In Kennedy’s dialogue with the broadcast journalist Walter Cronkite on 2 September 1963, the US president said, “I don’t agree with those who say we should withdraw. That would be a great mistake… this is a very important struggle even though it is far away”.

A week afterwards on 9 September 1963, during an NBC interview Kennedy reiterated, “I think we should stay” in Vietnam because withdrawal “only makes it easy for the Communists”. Three days later on 12 September Kennedy expounded, “What helps to win the war, we support; what interferes with the war effort, we oppose”.

On 26 September 1963, less than two months before Kennedy’s death, he said that America stations troops in Vietnam and other nations because “our freedom is tied up with theirs” and the “security of the United States is thereby endangered” if they pass “behind the Iron Curtain. So all those who suggest we withdraw, I could not disagree with them more. If the United States were to falter the whole world, in my opinion, would inevitably begin to move toward the Communist bloc”.

Read More: USA and China need to understand true costs of war

On 1 November 1963, Washington implemented a long-awaited coup that ousted the unreliable South Vietnamese dictator Diem. He was killed the following day, along with Ngo Dinh Nhu, his influential younger brother. Nhu had over recent months complained there were “too many US troops in Vietnam”. JFK was anxious for the coup to proceed and he placed the new US Ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., in operational command of it.

Kennedy believed that if the coup failed the US “could lose our entire position in Southeast Asia overnight”.

Dean Rusk, the US Secretary of State under Kennedy and successor Lyndon B. Johnson, later dismissed allegations that the former intended to withdraw, “I had hundreds of talks with John F. Kennedy about Vietnam, and never once did he say anything of this sort”.

Eight days before the assassination, on 14 November 1963 Kennedy told the media regarding Vietnam there was a “new situation there” following the coup, and “we hope, an increased effort in the war”. JFK continued that the US strategy should be “how we can intensify the struggle” so that “we can bring Americans out of there”. In Fort Worth, just a few hours prior to his death, Kennedy produced another statement saying, “Without the United States, South Vietnam would collapse overnight”.

Chomsky affirms that in the time leading up to Kennedy’s shooting, “there is not a phrase in the voluminous internal record that even hints at withdrawal without victory. JFK urges that everyone ‘focus on winning the war’; withdrawal is conditioned on victory… Nothing substantial changes as the mantle passes to LBJ [Lyndon B. Johnson]”.

Shane Quinn has contributed on a regular basis to Global Research for almost two years and has had articles published with American news outlets People’s World and MintPress News, Morning Star in Britain, and Venezuela’s Orinoco Tribune. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Global Village Space’s editorial policy.