What is religion? What is the right way to practice it? Why/how one’s faith is superior to that of others? How to live a life according to God’s Will? How to choose the right path, a path to salvation? Is it a part of one’s religion to judge and criticize others’ religion? Is it a religious obligation to not let people of opposite sects/groups live a life of dignity and shun their fundamental rights – even a right to breathe?

Answering such questions is a grave responsibility for whoever holds it, and it is a situation where one should have big shoes to hold and answer peoples’ critical questions. In our society, we name them Mullahs.

Read more: Did mullahs oppose Jinnah’s Pakistan?

The madrassa is an Islamic religious school that provides religious knowledge, teaches ethics, and transfers traditional knowledge to the next generation. During Pakistan’s independence in 1947, there were 245 madrassas; the number drastically increased during Zia-ul-Haq’s regime.

According to the Ministry of Religious Affairs in Pakistan, the total number of madrassas (registered) reached more than 22000 in 2020, teaching and educating 2M children. People follow religious leaders as ideals. And, in Pakistan, madrassas are highly criticized because they are considered sanctuaries of terrorism.

Read more: How a single religious ideology is impacting Pakistan

How religious extremism & sectarianism increased

Back in 1979, during the US invasion of Afghanistan, the US administration and NGOs actively supported the jihadists movement in Pakistan. Madrassas remained on top of the list. USAID provided $5.1M to design and develop the curriculum that promoted jihad and distributed books worth $13M in madrassas, Afghan refugee camps, and schools.

In addition, religious leadership, controlling and holding higher ranks in masjids, motivated the young generation towards jihad. Consequently, militant recruitment of youth in madrassas hiked. However, madrassas teach a narrow version of Islam that divides Pakistani society on sectarian grounds thus causing extremism to spiral out.

Read more: What’s causing extremism in Pakistan?

Now, how do such religious organizations form groups? Friday noon prayers are being stated as a ‘Filter and Coordination Point.’ On Fridays, gatherings take place in masjids where people gather in one place. During the research, a member who belongs to a religious organization said that religious organizations take advantage of big congregations and use Friday gatherings to start their activities.

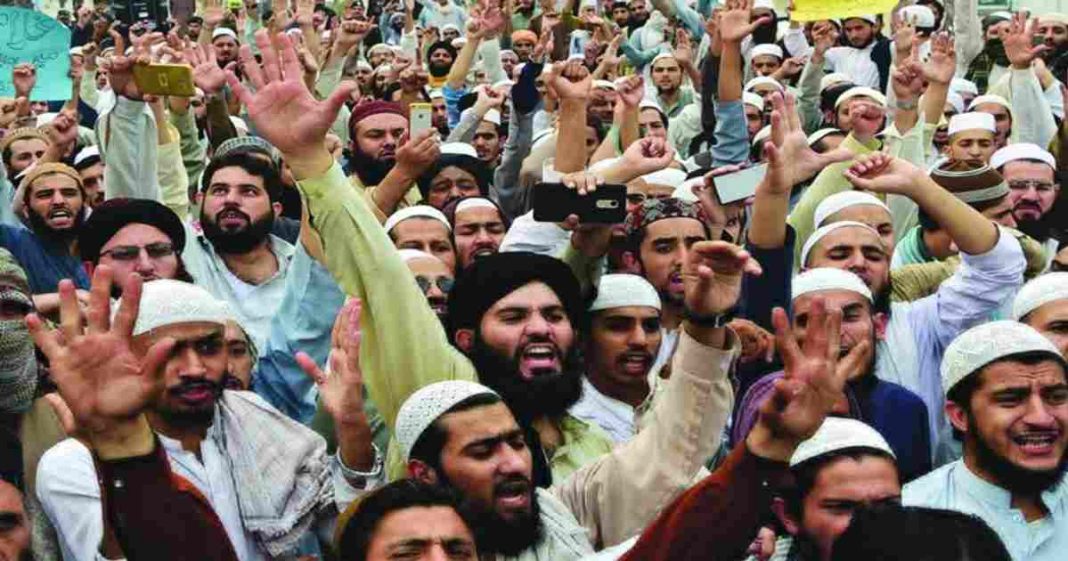

In this way, collective identities are established among groups, leading to street protests, calling extremist slogans, and targeting other sects. The religious organizations have strong state backings and are affiliated with other extremist organizations. They claim that it is easy to invoke the emotions of large gatherings gathered in one place.

Read more: Religious extremism in Pakistan: Genesis and a way forward

Failed efforts to curb extremism & sectarianism?

Pakistan’s government has shown concerns about this serious threat and formulated various policies to curb hate speech, extremism, and demonization of other religions and communities. For example, in 2018, in consultation with the National Terrorism Authority (NACTA), the Ministry of Interior prepared 44 subjects for Friday sermons to be disseminated across masjids in Islamabad.

The decision was made following the model accompanied by Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, where the state provides topics of Friday sermons to be delivered by the responsible authority. But, a leading authority of Friday sermons in Islamabad said that ulema will help the government against extremism and sectarianism but will not accept pre-written sermons for Friday prayers.

Read more: Sectarian rift a serious but not endemic issue in Pakistan

Paigham-e-Pakistan bill was passed in 2018, signed by 1829 scholars – belonging to nearly all the sects. The bill was a declaration against extremism and sectarianism. It encompassed suicide attacks against the state, spreading sectarianism, and calling jihad without the state’s consent.

But ironically, the state gave custodianship of the bill to a banned religious organization; as a result, radical and excluded sectarian groups hibernated under cover of this bill – that might result in the re-emergence of such groups.

Read more: Rise of religious parties: blind love or hybrid war?

Similarly, recently the Council of Islamic Ideology announced the formulation of a book of Friday sermons that would contain 70 topics highlighting social issues faced by the society. And afterward, it is exclaimed that the book will serve as a guideline and not be forced upon the prayer leaders. However, it will provide similar knowledge on social issues to different schools of thought.

Lack of political will?

Since its independence, Pakistan has been through many episodes of sectarian violence, religious intolerance, upsurge in inter/intra sect tensions – all leading to a less tolerable and highly radicalized society for people to live in. According to Global Peace Index 2021, out of 163 countries, Pakistan ranked 150th most peaceful country. Afghanistan comes next to Pakistan and stands at the 163rd position – categorized as the least peaceful country.

Some intellectuals spend the whole of their lives seeking answers to questions I have enlisted earlier. For them, it is essential to differentiate between right and wrong irrespective of their religious belonging. But, apart from them, there exist people who feel resonant for having affiliations with the religious organizations, and feel honored that they are serving their lives for a holy cause because they treat themselves as the custodian of best religious practices.

Read more: Force-the last resort while dealing with religious fault lines

Pakistan is not short of policies but a political will and stakeholders’ consensus. The security situation is deteriorating every now and then, yet we lag in answering who has to take the responsibility on their shoulders; political leaders, religious leaders, people themselves, or the external forces?

The author is a master’s scholar from the National University of Science and Technology. and has studied Peace and Conflict. The author can be reached at: hiramasood330@gmail.com.The views expressed in the article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Village Space.