During the time of global financial crisis of 2007/08, and while visiting the London School of Economics in early November 2008, Queen Elizabeth-II made her famous remarks about the financial crisis: ‘If these things were so large, how come everyone missed them?… awful… why did nobody notice it?’

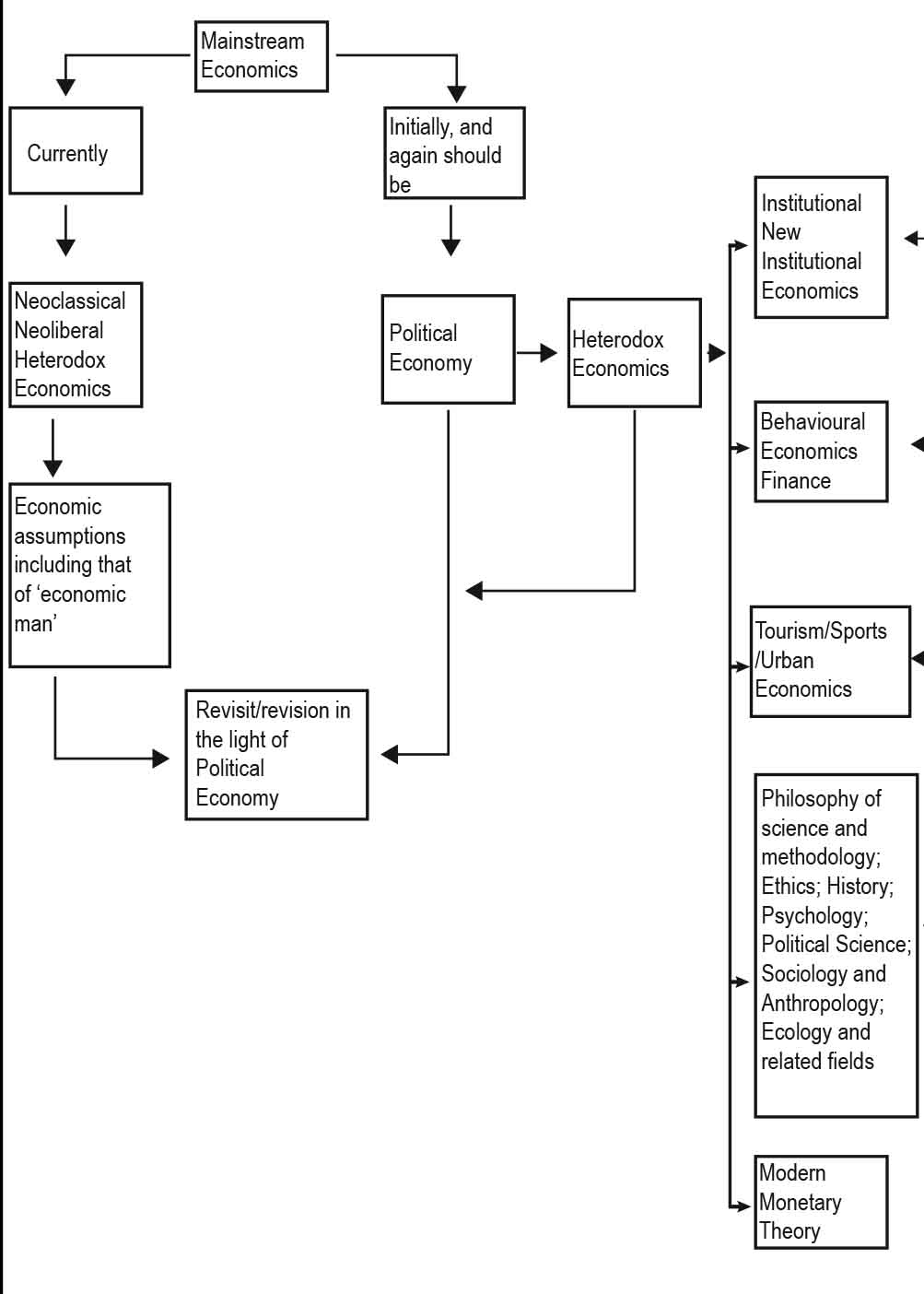

These words underline the need for revisiting the education of economics away from mainstream tradition to an alternative stream of political economy and whose spirit originates in heterodox economics.

The crisis in itself and the very apt remarks of the Queen served as watershed for research in this direction, mainly led by heterodox economic thought process; which was already coming out of the fringes to which it had been pushed. It was born out of the thought process of Adam Smith – a Scottish economist of the late eighteenth century and the founder of modern economics.

Queen Elizabeth-II made her famous remarks about the financial crisis: ‘If these things were so large, how come everyone missed them?… awful… why did nobody notice it?’

He took political economy and put it on elaborate and sound footings an approach that absorbed from not just economics, but also other social science fields such as sociology, psychology, and others that explained life itself.

Economics up till the middle of the nineteenth century continued to be pluralistic with the political economy approach as mainstream. It valued equally the positive as things are and normative as things should be aspects in terms of defining economic goals.

Read more: Pakistan’s Painful Economics, What more the IMF expects?

Hence, one found that instead of economics, political economy was primarily taught in educational institutions around the world, and in the tradition of Adam Smith himself who not just wrote the famous, ‘The Wealth of Nations (1776)’ but also before that, ‘The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759).’

This initial focus of economics shifted towards the positive side, as the ‘Scientific Method’ in the world of pure sciences took center-stage around the middle of the nineteenth century.

Economics up till the middle of the nineteenth century continued to be pluralistic with the political economy approach as mainstream.

This meant political economy now became economics with a narrower focus and mostly contained those theories that were backed by testable evidence or empirics. In time, this brand of economics became mainstream economics and was taught around the world in capitalist societies, including Pakistan.

On the other hand, political economy approach was adopted by social democratic societies like the Scandinavian countries and it is no surprise that these countries scored highly, over time, in economic and welfare indicators in the list of OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries.

Read more: Stagflation and it’s prevalence in Pakistan

Political economy, therefore, got relegated to the fringes. Yet, the frequent economic crises since the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, the practice of neoliberal or neoclassical economics through widespread International Monetary Fund programs, and the central-place of mainstream economics in policy formulation, all brought back attention to revisiting the approach taken by mainstream (or neoliberal or neoclassical) economics.

The statement of Queen Elizabeth, therefore, makes a lot of sense and directs economists to identify their own folly of trying to make political economy into economic science.

Institutional economics also takes into consideration ‘the path-dependent nature of man’ and in doing this directs students to view current economic activities in historical context.

They wrongly believed that by developing economics on the principles that are best suited to explain ‘natural phenomenon’ they could achieve virtually accurate understanding and predictability about human behavior and how the ‘economic man’ interacted; ironically this led to less foresight of economic happenings over time.

In order to quantify human behaviour, economists took a narrow approach of relying only on a certain number of measurable events, and made unrealistic assumptions about an economic (or sometimes ‘rational’) man that did not exist in reality, whereby, such people are ‘…utterly selfish, pleasure-maximizing automatons, who respond in predictable ways to all stimuli’.

Read more: House cleaning the economy

This assumption of a man to be predictable, not only allowed mainstream economics to borrow and practice the concept of ‘equilibrium’ from Physics, but also led them to conclude that left on their own, the sum of these economic men (or persons), and the economic entities they formulate would achieve market equilibrium, and there was little need for government intervention.

On the contrary, human affairs and behaviors are a ‘social phenomena’, based in turn on a multitude of social and political influences, and not just economic; underlying, therefore, the importance of approaching economic phenomena from a political economy perspective.

The reason for mainstreaming this diversified approach into educational institutions and in policy practice is because, ‘Political economy… is more concerned [than mainstream economics] with the relationships of the economic system and its institutions to the rest of society and social development.

It is sensitive to the influence of non-economic factors such as political and social institutions, morality, and ideology in determining economic events. It thus has a much broader focus that mainstream economics.’

By mainstreaming political economy like it was during the late eighteenth to the middle of nineteenth century, mainly through the works of such intellectual giants as Adam Smith, Karl Marx and Thorstein Veblen other fields of heterodox economics that have developed under this tradition over time will also get the necessary attention they deserve because they help students, researchers, and policy practitioners in making a more complete use of the knowledge base of political economy.

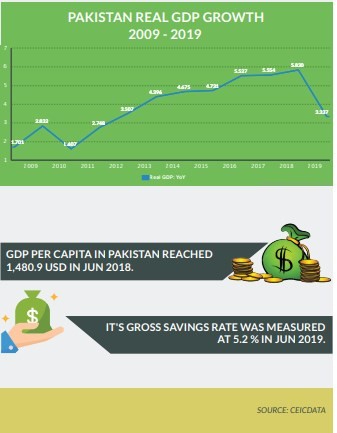

That is why in many countries developed and developing active practice of mainstream economics has led to huge increases in income inequality and poverty levels, not to mention the lack of growth of real wages and living standards of labour, given the centrality of ‘profits’ as the main motivation of economic activity in this brand of economics.

Prominent among them include institutional economics and behavioral economics since they advanced the initial scope of political economy. This is because institutional (and the related ‘new institutional’) economics approaches the economic man and his actions from the perspective of informal institutions belief systems, norms, and culture and formal economic, political and social institutions; all of which form the core of the broader approach taken up by political economy.

Institutional economics also takes into consideration ‘the path-dependent nature of man’ and in doing this directs students to view current economic activities in historical context.

Behavioral economics (and in turn the field of behavioral finance) allows approaching economic actions in the light of human traits acquired both over time and through current interactions. All of these fields basically help understand this economic man, and how he will behave.

This approach, therefore, brings much-needed predictability that the Queen referred to. This approach is not just theoretical since as mentioned earlier, many of the Scandinavian countries have adopted this political economy approach; for example, the successful social welfare model of Sweden is based on this approach.

It, therefore, gives a chance to the academic institutions of the capitalist world to learn from these countries. Currently, the education of economics is basically following in the footsteps of the neoclassical or neoliberal tradition of economics.

This tradition evolved, to give primacy to mathematics and statistics in approaching understanding and representation of economic phenomena. Important landmarks in this evolution included the work of Alfred Marshall in his book the first textbook of economics ‘Principles of Economics (1890)’, which later on came to be known as the field of ‘microeconomics’.

Read more: PTI is responsible for Pakistan’s economic mess..?

This field was later on further theorized on the aggregate economy level by J. M. Keynes through his main work, ‘General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936)’, which came to be known as the field of ‘macroeconomics’. Later on, Paul Samuelson combined the above two brands of mainstream economics and called his book ‘Economics (1948)’, which came to be known as ‘neoclassical economics’.

Neoclassical economics adopts a very unrealistic understanding of economic man, in terms of the assumptions that it makes (as indicated above) and the over-simplified and narrow model it uses to understand and predict economic happenings.

Moreover, the limited role of regulation especially financial regulation and that of government in bringing equilibrium in markets that mainstream economics advised has not allowed reaching efficiency and equity concerns.

That is why in many countries developed and developing active practice of mainstream economics has led to huge increases in income inequality and poverty levels, not to mention the lack of growth of real wages and living standards of labour, given the centrality of ‘profits’ as the main motivation of economic activity in this brand of economics.

Education of economics in Pakistan and overall, needs a revisit and a change of focus to go back to the initial thinking of modern economics, whereby the wider approach of political economy is adopted.

Having said, neoclassical economics is well-entrenched in most of the national and international educational programmes of economics, as found in Pakistan. Hence, a revisit of education of economics is essential in the light of above.

To better understand, in most universities, for example, the pre-requisite criteria for entry into PhD programmes in economics revolves around knowledge of microeconomics, macroeconomics, mathematics, statistics, and econometrics (statistical economics), along with passing a scholastic aptitude test (most often GRE), which once again tests knowledge of mathematics, and also English language. Sometimes, a preliminary understanding of economic history is also asked for.

This indeed is a very limited way of approaching the subject of economics. The list of pre-requisites, indicated above, for advanced/graduate-level study means that the under-graduate economics programmes are also basically focused on the same subjects. T

his has resulted in a supply of economists that have narrow understanding of economic issues; hence requiring a revisit of education of economics on the lines of political economy, and the heterodox subjects that have evolved in its tradition over time.

Apart from the ones indicated above, there have also evolved (and are now being taught in some universities) specialized applied subjects of economics that are basically influenced by the wider political economy approach and include, tourism economics, sports economics, and urban economics, among others.

Read more: Naya Pakistan’s mixed economic policy signals?

To explain further, the reason students of mainstream economics are limited in their approach and training is because the focus of economics education hardly ever takes into consideration ‘[a] Philosophy of science and methodology… [b] Ethics… [c] History beyond a single course, to help economists understand the evolution of the economy over time… [d] Psychology… [e] Political Science… [f] Sociology and Anthropology… [g] Ecology and other [related] sciences.’

Any future revisit of education of economics should include the above subjects into economics programmes for better wholesome education of students. Education of economics in Pakistan and overall, needs a revisit and a change of focus to go back to the initial thinking of modern economics, whereby the wider approach of political economy is adopted.

Here, apart from the heterodox subjects indicated above as against the current mainstream emphasis on neoclassical or orthodox economics other developments in the overall heterodox tradition should be included, mainly the subject of Modern Monetary Theory. The role of Higher Education Commission in Pakistan and similar entities worldwide is very important for leading the process for this much-needed revisit.

Dr. Omer Javed is an institutional political economist, who previously worked at the International Monetary Fund, and holds PhD in Economics from the University of Barcelona. He tweets @omerjaved7.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Village Space.