Police are the entry point of the criminal justice system. Though the pull of the status quo forces is much stronger than the push of the forces for change in the country, the perennial struggle between the two continues unabated.

The landscape of police reforms, in this regards, serves as a barometer of change in the justice sector. The emerging work on police reforms shows that the efforts towards changing police and policing in Pakistan can be thematically divided into strategic (policy-related reforms) and tactical reforms (service delivery related).

On the strategic level, momentous improvements are aimed at by amending the legal framework and by affecting the governance of police; on the other hand, the tactical changes target improving the day-to-day working of the police. Due to the paucity of space, a brief survey of strategic/policy-related reforms, during the Years 2019 and 2020, is presented.

Read more: Pakistan desperately needs Police reforms

The 2019 police reforms committee report

The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan (CJP) vide a notification in the capacity of the Chairman Law and Justice Commission of Pakistan (LJCP) constituted a Police Reforms Committee comprising retired police officers in 2018.

The Committee included officers who had led police reforms in yesteryears. The Committee deliberated and presented its report in January 2019 on three terms of reference that looked at model police law, urban policing, counter-terrorism, investigations and cross-cutting issues qua other laws.

The Report was sent to the Government of Pakistan for implementation, and in the meantime, the CJP constituted an Implementation Committee comprising retired police officers and serving Inspectors General of Police of all provinces and three territories and started overseeing the implementation of service delivery related reforms recommended in the Report.

Read more: CJP orders to verify degrees of all police officers

Constitutionality of Police

After the abolition of the concurrent legislative list through the Eighteenth Constitutional Amendment in 2010, the provinces started legislation on police as a provincial subject of legislation.

The interpretation of the 18th Amendment without appreciating articles 142 and 143 of the Constitution led provinces to think that the federal government has no role in policing. This view directly affected the governance of police and when it came to the appointment of IGP of a particular province, the matter was taken up by courts.

The Sindh High Court in Shehri Citizens for Better Environment Case (CBE Case) held that police, as a subject of legislation, is a provincial subject, constitutionally. The view was, however, not upheld by the Supreme Court of Pakistan that held, on the touchstone of articles 142, 143 and 242 of the Constitution, that police are a concurrent subject and both federal and provincial governments can legislate on it.

Read more: Internationalization of Police Reforms

After the 18th Amendment, like the rest of the provinces, Sindh had enacted the Sindh (Repeal of the Police Order,2002 and Revival of the Police Act,1861) Act,2011.

The Supreme Court’s reversal of the decision of CBE Case led to a re-enactment of the Sindh (Repeal of the Police Act, 1861 and Revival of Police Order, 2002) (Amendment) Act 2019.

Islamabad Police works under the Police Act, 1861. The Police Order, 2002 never applied to it. In 2020, five members of parliament drafted a model law for Islamabad Police and titled it as ‘Islamabad Model Police Bill’ (IMPB).

The IMPB was taken up by a sub-committee of a committee on the interior and was deliberated for a while. The IMPB was then referred back to the main committee on the interior after the government requested to examine it with a draft police law, which it was mulling to introduce after the cabinet’s approval.

Read more: Islamabad Police performance review, 552 criminals arrested in June

Gilgit Baltistan Police Bill, 2021

Apropos to the quasi-constitutional arrangement put in place after the Supreme Court’s decision on the legal framework for Gilgit Baltistan (GB), efforts are being made to introduce GB Police law.

The law is primed on the template of Police Order, 2002 insofar as the rights and responsibilities of police towards the public at large are concerned. The draft police law envisions constituting specialized units in police catering to investigation and forensics.

It also proposes a criminal justice coordination mechanism that brings all the stakeholders of the criminal justice system together on one table to collectively work for the safety and security of citizens.

It provides for establishing democratic oversight through a cabinet’s committee. In addition, it proposes to constitute tourist police, Khunjerab Security Force (KSF) under DPO Hunza and Key Points Police (KPP) to police vital installations.

Read more: Who will form government in Gilgit-Baltistan?

Policing newly merged districts in KP

The KP Police Act, 2017 provides ample powers for IGP to administer police. Two sets of amendments have been initiated to restore the dual system of responsibility in law and order situations (making both Deputy Commissioner and Head of District Police responsible) and to dilute the power of IGP in the appointment of the head of police intelligence unit.

After the Twenty-Fifth Constitutional Amendment that merged Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) into the mainstream KP, two enactments were passed to mainstream the policing services in the Newly Merged Districts (NMDs).

By enacting the KP Levies Force Act, 2019 and the KP Khasadar Force Act, 2019, two police forces of Levies and Khasadars were reconstituted under the law and put under the administrative control of IGP and given the responsibilities provided for police in the KP Police Act, 2017.

The two enactments provided for a scheme of absorption of the two forces into the KP Police. The non-proliferation of policing organizations is likely to cement the authority of the state if the requisite and supplemental budgetary and administrative system is established in the NMDs.

Read more: Two KP Policewomen join UN peacekeeping mission in Sudan

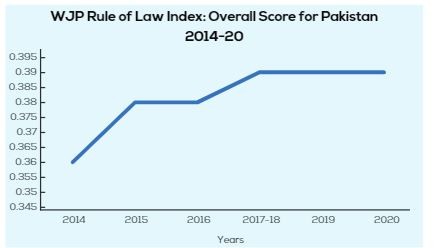

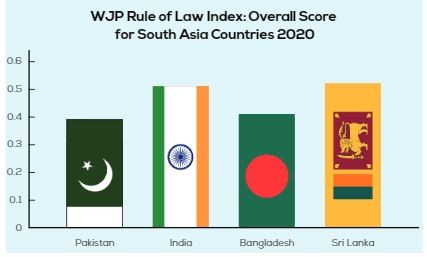

The Global Rule of Law Index, 2020 places Pakistan at 120 out of 128 countries; the placement is not very attractive, but the above-stated strategic police reforms show that there is will in the state and society to bounce back.

The alignment of police reforms with a larger rule of law paradigm will not only improve the internal security of the country but will also help it improve its credentials internationally by adhering to international human rights law in a systemic manner.

Read more: Police Reforms: Issues, Effects, and a Way Forward

Kamran Adil is a senior police officer, currently serving as Additional Inspector General Police. He studied law at Oxford University and writes and lectures on international law. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Village Space.