Lightning McQueen Inspires a New Generation of Car Enthusiasts

Has Lightning McQueen turned a new generation onto cars?

Has Lightning McQueen turned a new generation onto cars?

Cars was the first film we took my younger brother to see in the cinema, and he loved it so much that we had to go back and watch it another three times. So I suppose I have him to thank for my Lightning McQueen mega-fan status.

In case you’re unfamiliar, this Golden Globe-winning 2006 Pixar film tells the story of an arrogant, anthropomorphic Nascar-esque oval racer who’s in with a shout of winning the prestigious ‘Piston Cup’ in his rookie season.

After an unlikely three-way tie for the title in the final race, the series organisers hastily arrange a decider the following week on the other side of the country, and hero McQueen duly sets off in his truck, Mack, to head to the fictional Los Angeles International Motor Speedway.

During the night, Lightning is separated from Mack after he rolls out of the back of the truck, leaving him stranded on the famous Route 66, and while frantically trying to find his way back to the interstate, inadvertently rips up the high street of a backwater town called Radiator Springs.

Forced to stay until he repairs it, he begrudgingly gets to work, keen to make it to Los Angeles in time for the race. During his quasi-confinement, he meets Doc Hudson, the cantankerous town mayor who turns out to be legendary three-time Piston Cup winner Hudson Hornet. After a fractious start, Doc becomes McQueen’s mentor - and later his crew chief at the tiebreaker race, where McQueen nobly sacrifices a guaranteed win to attend to one of his rivals after a crash - his short small-town sojourn having taught him the values of empathy and kindness.

Sorry for the spoilers, but you really should have watched it by now.

The notion of a stuck-up "cooler-than-everyone-else" athlete type – complete with obnoxious “Kachow” catchphrase – being humbled by a tight-knit community of misfits, and learning how they thrive by relying on each other is just so wholesome. It leaves my heart full every time I watch it.

Let’s not forget the phenomenal soundtrack either, which features hits such as Life is a Highway by Rascal Flatts (a fantastic karaoke choice), the iconic Route 66 by John Mayer and the mood-boosting opener, Real Gone performed by Sheryl Crow. Truly one of the best movie scores out there, and you bet it was a mainstay of my iPod Nano playlist.

Everything about the film holds real nostalgic value for me, and watching it brings back happy memories of the mini Radiator Springs my dad made for my brother one Christmas. It contained die-cast models of all the Radiator Springs sitting next to their respective businesses. Luigi the Fiat 500 was manning his tyre shop alongside Guido the forklift, Sarge the Willys Jeep proudly guarded his army surplus store, and of course Sally the 996-generation Porsche 911 was waiting to welcome guests to her traffic cone-themed motel.

Probably the main reason that I love this Disney classic, though, is that it reminds me of the good old days when I didn't have adult responsibilities and all I had to worry about was beating my brother's high score on the accompanying Playstation 2 videogame (an oft-overlooked gem). But I owe its creators a debt of gratitude for instilling in me at an early age the notion that cars can have personalities and fantastic stories to tell - even if they don’t have eyes and tongues in real life. Oh, and true to form, Cars 2 is definitely nowhere near as good as the first one, and I will die on that hill.

Emissions scandal ten years on how Europe’s car industry is fighting back and shaping...

Emissions scandal changed the industry for good, forcing Europe's biggest firms to completely change tack

Emissions scandal changed the industry for good, forcing Europe's biggest firms to completely change tack

Ten years ago, on September 18, 2015, the automotive industry changed forever with one 'Notice of Violation’ issued by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). That might sound dry, but it was a bombshell that rapidly shook the entire automotive world.

The EPA notice revealed "irregularities" in the nitrous oxide (NOx) emissions in the emissions tests results of vehicles fitted with certain Volkswagen Group diesel engines – and alleged that undisclosed engine management software had been used since 2009 to essentially cheat the tests.

The initial recall was for 482,000 cars, but the Dieselgate scandal unravelled quickly from there. The Volkswagen Group soon admitted that the ‘defeat device’ had been fitted to around 11 million cars sold worldwide; within days, billions were wiped off the German giant's share price, while chief executive Martin Winterkorn quickly progressed from showing contrition to resigning.

In the following years, the Volkswagen Group spent billions on compensation and fines and numerous members of its staff faced civil and criminal prosecution. But the impact of Dieselgate wasn’t just limited to Volkswagen: it had a profound impact on the whole industry, not least because several other firms have since admitted using cheat devices of their own. And the effects of it are still being felt a decade later.

In the wake of the scandal, car makers – led by Volkswagen – began a pivot towards EVs in an attempt to literally clean up their act. But they soon had cause to: governments and lawmakers, particularly in Europe, decided that the car industry could no longer be trusted. After all, they were the bad guys who couldn’t be trusted to do the right thing.

That led to the increasingly tight CO2 emissions standards and ultimately the measures to phase out the sales of petrol and diesel cars. And while environmental concerns among the public would probably have pushed governments into introducing some requirements on the car industry, measures such as the EU’s current 2035 cut-off for ICE car sales and the UK’s zero-emission vehicle mandate, which also has a 2035 goal, were developed without significant input from manufacturers.

The challenges of such mandates for the industry have been clear: car makers are essentially being asked to sell EVs at a volume for which there currently isn’t the public demand, while also having to nearly double their line-ups and development costs to continue a parallel line of ICE cars for markets that don’t have such mandates in place.

But in recent months, it feels like something has changed, and it was in evidence talking to a number of industry CEOs at the Munich motor show recently. The European car firms seemed to have their swagger back – and were out to take on the law makers.

The BMW Group's Oliver Zipse, Stellantis's Jean-Philippe Imparato, the Renault Group's François Provost and the Volkswagen Group's Oliver Blume were among the bosses who spoke out forcefully and eloquently against the EU’s 2035 ban. They argued for broader ways of promoting CO2 reduction, systems less focused on what a car produces at the tailpipe and more on lifetime emissions. They pushed for the freedom to develop technologies that could prove an alternative for EVs, such as e-fuels. And they did it all while insisting that they just wanted to give car buyers what they wanted.

It seemed to be an organised, concerted pushback from an industry that sensed an opportunity. The public villains of Dieselgate, the ‘evil’ companies that needed to be controlled, were trying to seize the moment to position themselves as a force for good in the face of rising public resistance to EVs. A significant chunk of the public just want simple, affordable cars; the car industry wants to offer them. And, their argument goes, they could – if legislators would let them.

The early signs have been positive for the industry. Following various talks, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen has indicated support for a new ‘E-car’ class for small, European city cars enabled by less onerous legislations – even if she did say that EVs remain the ultimate goal.

Of course, there is some irony that this industry pushback comes as European firms are finally beginning to launch desirable and relatively affordable EVs, which arguably wouldn’t have arrived so quickly without the strong regulatory push set by those 2035 targets.

Ultimately, few will question the need to reduce emissions, and it’s clear that, longer-term, the future is electric: this is a fight over the timeline of that transition.

A balance is clearly needed: Dieselgate showed that no industry should be left essentially unchecked and that profit-chasing major corporations can’t necessarily be trusted to do the right thing. But there’s also no doubt that car firms are at their best when given a problem to solve and then given relative freedom to find solutions.

This industry is full of amazing engineers, technicians and problem solvers who can help shape a brighter future. It’s time to demonstrate that they can be trusted to do so again.

Driving instructors the unsung heroes guiding us through every first drive

Instructors have ice in their veins – and a foot over the dual brake pedal

Instructors have ice in their veins – and a foot over the dual brake pedal

Everyone’s got a story. From slipping and sliding around an abandoned field to stalling innumerable times in a whisper-quiet side street, it seems nobody’s first time driving a car goes all that well.

Yet, on most occasions, it’s a tale told through a smile. What should be a deeply overwhelming experience ends up being joyful, and I reckon it’s all thanks to that most unsung of automotive heroes, the driving instructor.

They teach us about everything from biting points to brake distances with a seemingly universal dry wit, maintained despite a background of long hours, months-long waits for test slots and what must be among the most treacherous working conditions in civilian life.

These brave souls wake up every morning and willingly strap themselves into the passenger seat of a tonne or more of fast-moving metal, with a total novice at the controls.

Surely, I wonder, they must stir their coffee mulling what close shaves they’ll have today. Will it be errant acceleration into a pack of parked cars, an attempt to circumnavigate a roundabout anti-clockwise, or the failure to register a group of schoolchildren entering a zebra crossing?

They carry a great deal of responsibility, not just in protecting the learner in their guardianship but also the wider community exposed to the rookie at the wheel.

Given the sheer complexity of the modern car, that’s no mean feat. I learned in a Ford Focus with a standard throttle, brake and clutch, but also a button-operated handbrake, drive mode selector, reversing camera, speed limit detection and an overly paranoid emergency braking system.

That was daunting, but throw in the bings and bongs mandated by new legislation, or the awkward powertrain blending that can be introduced by electrification, and I can see it being downright overwhelming for a newbie.

Yet the sage in the passenger seat just powers them through it. Whether it’s a nurturing, guiding hand as they gradually paddle their way through side streets, or the hairdryer treatment after grating the nearside wheels on a high kerb, the driving instructor just has a way of making it work on most occasions.

Indeed, the UK’s driving test pass rate tends to hover at just shy of 50%, indicating instructors are largely keeping the overall system in balance.

I also have some appreciation for the emerging community of video instructors. With just a quick search online, you can find a professional describing your local test route just about wherever you live, in pretty much every kind of car you would learn in.

They’re fantastic for highlighting pain points and those silly (or worryingly dangerous) mistakes that learners tend to make on failed test attempts.

But it’s also rather good entertainment. I’m a particularly big fan of Conquer Driving, an instructor on YouTube who explains concepts in a way the budding enthusiast really understands. It’s his videos that taught me how to get a manual car moving quickly under pressure, and then how to rev match.

Even if you’ve been driving for yonks, I bet you’ll learn something from one of these instructors that you hadn’t previously considered.

I might even go so far as to suggest they’re the true petrolheads among us, laying their wellbeing (or at the very least their wealth) on the line so that we can all take to the roads ourselves.

Car Design Why Challenging Styling Is Taking Over and What Drivers Really Want

Bentley can’t have been surprised by the reaction to its EXP 15 that was revealed a few months ago

Bentley can’t have been surprised by the reaction to its EXP 15 that was revealed a few months ago

Ever see something online and sigh and think that you know what the comments are going to be like? That’s how I felt when I saw the studio pictures of the Bentley EXP 15 concept car.

I feel like I could have told them. And while I know that what people say on social media is not a true representation of what the public thinks, especially those who can afford a Bentley, there is enough ‘Jaguar-lite’ and ‘yikes’ sentiment to see that this is a challenging car.

Bentley must have known that, mustn’t it? The EXP 15 is not set for production but that doesn’t mean it won’t inform the cars Bentley will make in future.

The company has form here: remember the EXP 9 F from the 2012 Geneva motor show? It was not exactly a looker, was not widely gracefully received, and while not destined for production in that form, it did preview the Bentayga, which arrived looking even worse.

‘Challenging’ seems to be a word of the moment. Even Julian Thomson, the General Motors designer who has created some truly beautiful cars, used it in our interview with him last month.

Designs, he thought, should challenge; although he works in an advanced design studio so he has more reason to believe that, and there’s nothing ungainly about his studio’s latest Corvette concept. But designers today do seem to like cars that are challenging. They like dissonance. Why?

Clearly it’s a choice. Car designers know what beautiful is because they’ve studied it, and they’re beautiful people with beautiful lives, houses, dogs and partners, and they can pull off wearing suits with trainers.

When it comes to dating apps and sessions on Rightmove, are they swiping yes on ugly people and houses because they’d like to be challenged? Because it doesn’t seem so.

So why the challenge when it comes to cars? Why should a car be difficult to look at? An argument goes that you think a car is beautiful straight away and then over time its appeal will fade. It’s too obviously pretty, or bland.

But I’m not sure I buy this. Wasn’t the Aston Martin DB9 immediately a stunner? To my eyes, it still is. Wasn’t the Porsche Cayenne a gomper at birth? And I’m afraid I’d still swipe left if its mug appeared on Tinder.

Besides, isn’t life challenging enough? Earlier today, I spent an hour typing one-handed on a train that had standing room only in its four (clearly too few) carriages. My motorbike insurance renewal was just offered to me with a 67% price hike, necessitating a drudge through comparison websites.

The new policy documents tell me it will automatically renew, which I didn’t ask for and was given no option to opt out of; remembering this will be another drain on my inadequate mental capacity. Four members of my family have been in hospital in the past three months.

The road surface is failing outside my house. My local council has launched another survey about planning, which I will fill out, even while knowing the council will ignore the views of the majority of residents.

The book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness introduces a theory called Sludge. It refers to any kind of friction that impedes your life: those hours you spend on hold to a call centre; the hidden fees; the small print; the appeals you must go through when you get an erroneous parking ticket (my family have had three in a year, all overturned when I’ve appealed them, but by gum it’s tiring).

I am an exceptionally fortunate man with an easy and comfortable life, good health, a loving family and a wonderful job. Yet even I can get exhausted by the system. The sludge.

This, clearly, is not a car designer’s fault, but into this melee, this strife, why introduce more challenge when it could take us out of it?

The good people at Morgan think of their cars as escapism, something to get us away from the toil, the ball-ache and the drama of life.

I appreciate that making a challenging-looking car doesn’t stop people buying one, because Porsche’s long-running best-seller illustrates that. But I’m tired of my eyes being challenged. I want them to light up like

I’ve just seen a dog with its head poking out of a car window. What’s so bad about making beautiful cars?

Why Bold Innovation at Mercedes Is Hidden Behind Outdated Design

The new GLC is just as radical under the skin as the BMW iX3 and Audi Concept C, but its styling bores

The new GLC is just as radical under the skin as the BMW iX3 and Audi Concept C, but its styling bores

Whatever you think of the new styling directions at BMW and Audi, they don’t half shine a light on the rut that Mercedes finds itself in.

The new electric Mercedes-Benz GLC is just as shiny and new underneath as the BMW iX3, yet in giving the model the same look as pretty much every other Mercedes launched over the past decade or more, a lot of that fresh approach is lost.

The innovation in the car underneath fails to cut through on the surface, no matter how many LEDs are in the new GLC’s grille.

Audi had been in a similar position to Mercedes until recently: styling stuck a constant evolution that after a while becomes samey and eventually even old in some of the surfacing and touches. You could guess what a new car would look like before the covers had even come off.

The recruitment of Massimo Frascella from JLR emphatically addressed that at Audi, and his vision for a new four-ringed look was seen with the Concept C, another Munich motor show star. Whether you like the Concept C or not, it is something different, something more daring, not just another iteration of what has gone before. It’s a starting point for change.

BMW has never been afraid to reinvent its look itself and has been the boldest of the German premium trio with styling revolutions. You won’t find many kind words about its most recent styling departure, but with the new iX3, it has shown that a look that started as quite shocking and polarising can be refined into something more contemporary and palatable. It works.

Since Gorden Wagener took the design helm at Mercedes in 2008, the styling direction has remained largely constant after he got his vision into the generation – and now generations – of cars that have followed.

What felt fresh and modern a generation ago under Wagener feels staid and done now. We’re ready for something else. Is Mercedes ready to take the design leap that its latest technology deserves?

How Volkswagen Reclaimed Its Roots to Make Affordable Electric Cars a Reality

Volkswagen, Cupra and Skoda each revealed crucial new entry-level EVs at Munich 2025VW ID Life concept never saw showrooms, but it was a crucial step towards a new family of entry EVs

The story of the Volkswagen Group’s push into the affordable EV segment can be told through its big reveals at the Munich motor show.

In 2021, the first time Germany’s biennial motor show was held in Bavaria, VW signalled its intent to enter the affordable EV segment with the boldly styled ID Life concept. It sat on the new MEB Entry platform, a front-driven electric architecture that would allow for vehicles costing around €25,000 (£22,000) from Volkswagen and sibling brands Cupra and Skoda.

The reaction wasn’t exactly positive: the car was a stylistic departure from both the ID models that had gone before it and VW’s long-running combustion-engined classics. The distinctly underwhelming reception contributed to a major Volkswagen management shake-up, which involved Thomas Schäfer being brought in as CEO and Andreas Mindt joining as design chief.

Straight away the pair started leaning into Volkswagen’s heritage. Schäfer has talked repeatedly about making Volkswagen a ‘love brand’ again, while Mindt will enthuse all day about the ‘secret sauce’ that all his designs must have.

But there were changes behind the scenes, too. The VW Group reorganised, with the new Core division – Volkswagen, Cupra, Skoda and Volkswagen Commercial Vehicles – working in a far more collaborative fashion on the new ID Entry project.

Schafer’s decision to embrace VW’s heritage led to the ID 2all concept, Mindt’s hastily designed vision of how future small Volkswagen EVs can be true to the heritage of the brand. The ID 2 all actually sat on the reworked platform of the ID Life, but it garnered a wholly more postive reception. It looked and felt like a Volkswagen, which, after the likes of the anonymous ID 3, was a huge step in the right direction.

That was ramped up at Munich two years ago, when Volkswagen showed the ID GTI concept, a car that took the 2all and ramped up the heritage aspects even further. The warm reception proved that Volkswagen is best when it plays to its strengths.

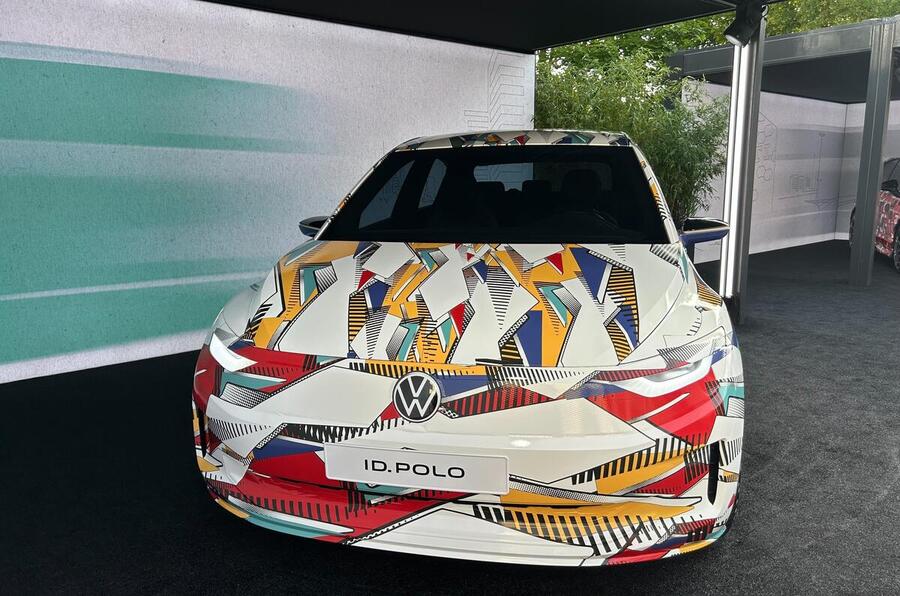

At Munich this year, that four-year quest to launch the £22,000 EV neared fruition with the unveiling (albeit hidden under camouflage) of near-production versions of the now-renamed ID Polo and ID Polo GTI, along with the closely related Cupra Raval and Skoda Epiq. And there was a concept version of the ID Cross that will follow those machines into production next year.

Again, delve into the specifics of the platform, powertrains and battery technology that will underpin those models and much remains from that 2021 ID Life concept.

The difference is that Volkswagen has realised its best chance of success in the new electric era, of fending off the vast ranks of aggressive Chinese rivals, comes from taking new technology and infusing it with the warmth and familiarity of proven Volkswagen design and model names.

It’s not an entirely new approach – Renault has found success with the 5 and 4 through a similar mix of new EV tech and retro design – but, for a brand with Volkswagen’s rich heritage, it’s a smart one. And while the path from the ID Life to the ID Polo hasn’t exactly been smooth, it’s a journey that should provide some important lessons for the future.

Why Modern Cars All Look the Same and Why It’s Getting Worse

BMW’s XM isn’t pretty, but at least you’d spot it in a line-up of Chinese SUVs

BMW’s XM isn’t pretty, but at least you’d spot it in a line-up of Chinese SUVs

Please tell me it’s not just me, dear reader, who sometimes looks at a new car – something I do on a more than occasional basis – and with the best will in the world couldn’t say what it is.

There are so many more new cars than there used to be, so many more of them are crossovers than they used to be and, by gum, so many of them look the same that I am, on occasion, utterly lost. I can’t tell one from another.

This is a new experience for me. I always proudly thought that if I witnessed a robbery I’d be able to tell the police what make, model and trim level a getaway car was, and I’d probably be able to name its colour and wheel design. Actually that may be a bad example, because I already know it will be an Audi RS3.

But let’s say an anonymous grey crossover is involved in a hit and run and a nearby copper asks me for a statement about what car was involved. I increasingly fear I’d have to shrug and offer up a simple: “Haven’t a clue, mate. One of those new electric SUVs. I think.”

Strictly speaking, thinking that all cars look the same isn’t a new phenomenon. In an issue of Performance Car I bought back in the early 1990s, the magazine printed a series of silhouettes of D-segment hatchbacks from the time: a Ford Mondeo, a Nissan Primera, a Toyota Carina and so on.

Their gag was that if you could identify none of them from their outline alone, you were a true Performance Car reader. But if you could tell most of them apart, you were an Autocar & Motor reader.

But while not a new thing, I think events have recently progressed at speed. I don’t know about today’s Autocar reader, but I can tell you this Autocar writer of two decades would struggle to tell plenty of new models apart even if they weren’t reduced to their silhouettes.

Even on a clear day I’m not at all confident I could tell a Geely EX5 from a BYD Atto 3 until I got close enough to read the badges. Why is this? Have all the good shapes already been taken? Are we now drawing the same ones again because, basically, we have to?

In national treasure (and Ferrari F12tdf owner) Hugh Grant’s rather grizzly new film Heretic, our villain tells a story, and it’s mostly true, of how Radiohead were sued by The Hollies because parts of Creep were taken from The Air That I Breathe. But then Radiohead got legal with Lana Del Rey because her Get Free sounded too much like Creep.

Are we just, y’know, running out of notes? And if so, is it really so surprising we’re running out of lines? There only so many ways you can draw around four wheels and a car’s oily (or electrical) bits if one also has to include the certain number and location of seats, doors, windows and lights, plus bumpers so soft that hitting a deer writes off the car. So the new Ford Capri looks a bit like a Polestar 2? Well, it has to look like something.

Maybe I should start being kinder to wilfully ugly cars. Say what you like about the absolute munter that is BMW’s XM – plenty of people have – but you will not mistake it for an Omoda 5.

I think electrification isn’t helpful. If you don’t need a grille to cool an engine then you don’t have a signature identifier in the most prominent position on the car. In fact, given that it would upset the aerodynamics so much – and that’s so important for an electric car’s range – you’d better not have one. A person can design plenty of different pretty shapes, but a wind tunnel will say only one of them is the most efficient.

That’s something that’s true of even the latest batch of hypercars. I can tell one of those from another, just about, but when outright performance is the overriding criterion, there is still only one way that will work best.

Perhaps, then, the surprise shouldn’t be that I can’t tell so many new cars apart. But that there are still so many I can.

Discover Ireland’s Untamed Roads Where Driving Dreams Come Alive

Empty roads free of average-speed cameras? You need to head west to Ireland

Empty roads free of average-speed cameras? You need to head west to Ireland

We’re all guilty of it: cooing over glass-smooth Alpine passes and stretches of notionally empty autobahn while failing to appreciate that some of the planet’s most captivating roads lurk on our doorstep. No, not J1-J2 of the M1 at 3am: Ireland.

Going for a spin in England and Wales purely for the thrill, joy or hell of it has become a faff. (I’m excluding Scotland here because, in general, it’s still superb.) With 40 million licensed vehicles out there, the sheer volume of traffic is problematic.

Then there’s your friend and mine, the Jenoptik Vector P2P. These lurid yellow, high-resolution average-speed cameras are not only commonly seen on the motorways but are now increasingly dotted along some of our country’s most scenic routes.

I’m not condoning speeding here; what I’m saying is that it’s damned near impossible to enjoy the ebb and flow of a good road when you are under constant scrutiny, which is distracting even when you’re not driving in a manner your mother would disapprove of.

As for potholes, we have plenty of those, but they’re a universal evil. On a recent US launch, one of Bentley’s comms chaps rued the fact two hugely expensive 23in rims ‘wouldn’t be coming home’. This on day one of a three-week event.

So, Ireland – both Northern and the Republic of. My eyes were opened to the delights of the latter in 2018 on the launch of the tweaked Mazda MX-5 (when the 2.0-litre engine went to 7000rpm). The back roads of Fermanagh (and of Leitrim and Donegal just over the border) were close to the Platonic ideal of a B-road.

They were well sighted despite their teasing, undulating, rollercoaster topography. They were well surfaced. They had really great rhythm. And they were quieter than expected. Google tells me England’s population density is 434 people per square kilometre.

That figure is 141 in Northern Ireland and 77 in the Republic (both are lower than that of Wales, too). So whoever it was in the Mazda press office that made the call to head west instead of to Spain or Sicily, well played.

Recently I found myself back in Ireland, this time bound for the south-west, in a personal capacity – a prenuptial rendezvous in delightful Dingle, home of Fungie the dolphin who lost his pod and an implausibly large number of drinking establishments.

Most of the guys turned to Michael O’Leary to get them to Limerick and ended up hiring Hyundai Tucsons from there. With the new BMW M4 CS in for its road test that week, and in on-brand green, fate was a bit kinder to me. I collected a friend who lives in Pembrokeshire and we took the ferry to Rosslare.

We made for Killarney the day before the official itinerary commenced. This gave us time to explore the Ring of Kerry and experience for ourselves what are supposed to be some of the most heavenly roads in all Ireland – and, we therefore surmised, the world.

Needing to get to Dingle by lunchtime, we chose our route carefully. Naturally 542bhp and an effective four-wheel drive system wouldn’t hurt, but going full Paddy Hopkirk wasn’t really why we were there.

After waking everyone at our B&B with that unmistakably nasal, impatient M-car cold-start idle, the following morning we left Killarney and traced the N71 south-west through the Middle Earth landscape between Muckross Lake and Looscaunagh Lough (if nothing else, you have fun wrapping your tongue around the names).

The M4 CS moves well for a big beast but, really, this is Caterham Seven country. Then it was the rugged, rallying mecca that is Moll’s Gap (named after the landlady who ran an unlicensed pub when the road was being built in the 1820s) and onto the R568 before we joined the flowing N70 as it meets the coastline before Caherdaniel.

Here the BMW was much more at home and poised through third-gear sweepers, but the real star was the breathtaking backdrop where Ireland meets the Atlantic. It’s a rival for the Hebrides.

Instead of completing the northern coast of the Ring, we cut inland at Waterville (if you need breakfast, hit the Beachcove Café) and wove our way up the Ballaghisheen Pass before heading north-west and onto the Dingle peninsula. Dingle itself sits on the south side of this spit of land, and the N86 is pleasant enough and will get you there pretty quickly.

Far better, though, to head to Stradbally and tackle what was once the most famous rally stage in Ireland, the Conor Pass, although it hasn’t been used for competition since the 2004 Circuit of Kerry Rally.

It’s the high point of our little tour, literally and figuratively. This wild corner of Ireland really does deliver.

Why Hatchbacks Still Outshine SUVs for Everyday Driving

Hatchbacks are smaller, lighter and cheaper than SUVs – and better, too

Hatchbacks are smaller, lighter and cheaper than SUVs – and better, too

It was at once an unsatisfying and actually a very satisfying verdict for a group test. When I put the revised Volkswagen Golf against a pair of rivals in the Toyota Corolla and Peugeot 308 last August, the overarching conclusion was that all three were thoroughly recommendable.

There were a bunch of alternatives that I didn’t include, simply because 10-car group tests are a logistical nightmare, but we could have brought the Mazda 3, the Honda Civic and the Ford Focus and the result would have been broadly the same.

You might conclude, then, that it doesn’t matter which C-segment hatchback you pick, because they’re all white goods. The opposite is true, though: in a world filled with slightly mediocre cars, here’s a market segment that is still bursting at the seams with excellence.

Although SUVs and crossovers have asserted dominance in recent years, combustion-engined C-segment hatchbacks have been the bedrock of the European car market, selling in their millions.

As such, manufacturers have invested money, time and effort into making them really good, and it shows. In many ways, the C-segment hatchback is simply peak car – as if Goldilocks turned out to be an automotive engineer rather than a porridge-pilfering vagrant.

They’re just the right size for European roads: not so small that you feel like you’re driving a Cozy Coupe and not so big that they’re a struggle to park or squeeze down hedge-lined country lanes.

You can just about fit a family in but you’re not then lugging around a tonne of redundant metal when you drive it by yourself.

That rightness of size starts a virtuous circle. Because these cars are not excessively heavy or excessively tall, they don’t need big engines to manage good performance. (The 148bhp petrol Golf does 0-62mph in 8.4sec. Do you really need more?)

And because they don’t have big engines, they can manage 50mpg without trying. Go for a diesel (if you can find one) or a hybrid and 70mpg could be within reach.

Because there isn’t all that much weight or height to control, the suspension can be fairly soft, which means that ride and handling needn’t be a compromise: you can have tight body control and direct steering without the ride turning rough.

It’s all done with less than exotic components, which means they’re not ridiculously expensive if they ever need replacing. Pair it with some 16in wheels with chunky tyres and you’re really winning: pillowy ride comfort and cheap tyres. Talking about cheap: any hatchback is usually a few thousand pounds cheaper than the equivalent SUV.

Quietly great to drive, practical, economical and affordable: if the C-segment hatchback were introduced today as a new idea or product, we would all go mad for it and call it a game-changer.

But because we have had the Golf for 50 years, the Corolla for 40 years and the Peugeot 306/308 for 30 years, familiarity has bred contempt. They are just seen as the standard, the thing that has always existed, the car your parents drove.

More practical than a saloon and more efficient and better to drive than an SUV, a hatchback is automotive bread and butter: hard to beat but not very fashionable. It’s just in need of a sourdough moment now.

Why Driving a Morgan Feels Like Pure Joy on Every Road

They do things differently in Malvern – and that’s how we like it

They do things differently in Malvern – and that’s how we like it

Driving a performance car in the real world can make you feel like public enemy number one.

Maybe it’s the overly aggressive styling of most modern driver’s cars, or perhaps it’s simply jealousy. But try pulling out of a busy junction in something with a fruity exhaust and a sub-4.0sec 0-62mph time, and settle in for the wait as your fellow motorists whizz wilfully by, glaring at you like you’ve just suggested demolishing their house to make way for a McDonald’s drive-through.

Conversely, try the same move in a 1950s MG A and you’ll be treated like a hero. People love classics. However, it’s incredibly easy to forget just how much automotive technology has evolved in the past 70 years until you have to deal with beam axles and carburettors.

So how do you blend exhilarating modern performance with cheerful, crowd-pleasing vibes? Simple: you buy a Morgan. I’ve never been treated better on the road than I have behind the wheel of one of Malvern’s hand-crafted roadsters, and even if I had been sneered at, I’d be having too much fun to care.

Operating since 1910 as a successful purveyor of thrummy three-wheelers, Morgan built its first four-wheeled car in 1935 and introduced the Plus 4 in 1952 – and then stayed firmly in its lane. The Plus 8 came about in 1968 with Rover’s legendary V8 up front, but otherwise this was a firm that steered clear of all-out revolution.

Nonetheless, the orders kept coming in (there were 10-year waits at one point), and in 2000 the Aero 8 was launched alongside the classic Plus models and the V6 Roadster as the first all-new Morgan in 32 years.

The looks were divisive, but it’s what was under the skin that made this car so special. A bonded aluminium chassis cradled a current-spec 4.4-litre BMW V8, while rose-jointed suspension and double wishbones all around meant the chassis was a world away from the somewhat cart-esque architectures of yore. It was truly modern, but still with a traditional ash wood body frame as a nod to the past.

Morgan was on a roll by 2012. If you weren’t a fan of the Aero 8’s gorgeous art deco styling, you could have a Plus 8 instead – near enough the same car but with a body that looked like it left the factory in 1956.

The 3 Wheeler was brought back to life too, with a thrummy V-twin bursting out of the body between the front wheels. And today’s Morgan line-up is more diverse and characterful than ever before: the laugh-a-minute Super 3 opens the range with a Ford petrol triple and unique styling; the Plus Four continues as a faithful but usefully modernised evolution of the 1950s original; and the new Supersport has landed as a six-figure GT with real Porsche-baiting credentials.

Visit the factory and not only will you find cars being beautifully hand-built in a similar way to 100 years ago, but you will also find buzzing engineering and design teams with a slickness and community spirit that’s firmly at odds with the firm’s former ‘old man’ image.

It’s a company that recognises the importance of keeping key skills going while appealing to the next generation. To me, Morgan is the King of Cool in the car world at the moment – and the jaw-dropping Midsummer special edition, created in partnership with legendary design house Pininfarina and launched last year, is a further illustration of that.

It’s hard not to crack a grin when you’re behind the wheel of a Morgan, and there’s something special about knowing that other people are doing the same just watching you drive past.