The recent spell of torrential rains literally drowned the city of Karachi for a few days, leaving the helpless masses at the mercy of the vagaries of the weather, with the state nowhere to be found. Businesses and individuals suffered losses worth billions of rupees.

The broken sewerage network, clogged stormwater drains and unplanned construction left little space for rainwater to drain, which ultimately found its way through people’s homes, offices and enterprises, sweeping away their fortunes. But it was not just the rains. The rains only washed away the smokescreen of a functioning city and exposed its ugly vulnerabilities.

What’s wrong with Karachi? A more pertinent question would be what’s right with Karachi since the city is one of the ten worst cities in the world on the Global Livability Index. The metropolis has a population of 16 million, though many claim that this is grossly understated.

Read more: What Pakistan has in store for Khan’s government?

Except for a few posh localities, which remain far beyond the access of a common man, the city is densely populated with dreadful air quality, poor road infrastructure, low-quality public transport system and severe water shortage. As per the World Bank, urban greenspace is now merely 4 per cent of city’s built-up area; 60 per cent or less population has access to public sewerage, and 45 citizens compete for every bus seat compared to 12 in Mumbai.

Even more alarmingly, the economic activity is gradually moving out from the city to its periphery, increasing urban sprawl and going diametrically opposite to government’s stated goal of vertical growth of cities. It was only last year at the launch of the State Bank’s policy for low-cost housing when the Prime Minister underscored his commitment to encouraging vertical urban growth to conserve green spaces and prevent overcrowding.

Karachi being the bastion of MQM, has been getting peanuts, even though it contributes 12-15 per cent to the national GDP. Over the next ten years, the city is expected to contribute $330-450 billion to the country’s economy

But the data from Karachi tells an entirely different story. As per the World Bank-sponsored city diagnostic and transformation strategy, “evidence from nighttime lights – a strong proxy for economic activity – shows declining economic activity in the core areas of the city (Karachi) and high growth on its periphery, indicating that high-value economic activity is moving away from the city core.

This stagnation of economic activity in the central areas is problematic for long-term economic and social potential”. The fact of the matter is that Karachi remains an unplanned and persistently expanding urban mass just waiting for a disaster to happen, and the record rainfall provided the trigger.

Notwithstanding these grave issues faced by Karachi, if one goes by recent political promises, it does seem as if the future of this city is finally destined to change. The PPP promised a development package of Rs800+ billion for Karachi and demanded a matching contribution by the federal government.

Read more: Pakistan’s way forward out of recurring economic crises

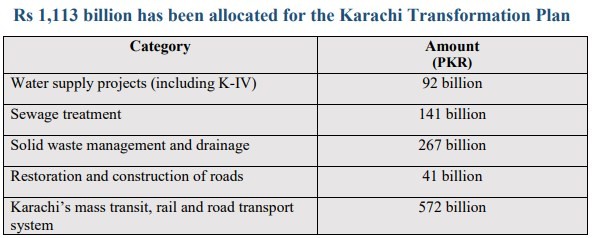

The Prime Minister Imran Khan then announced the grand Karachi Transformation Plan worth Rs1.1 trillion, including Rs92 billion for water supply; Rs267 billion for solid waste management, stormwater drains clearance and resettlement projects; Rs141 billion for sewage treatment plan; Rs41 billion for road projects; and Rs572 billion for mass transit, rail and road transport projects.

The plan is supposed to be supervised by an implementation and coordination committee headed by the Chief Minister Sindh, with members from PPP, PTI and MQM-P. This is music to many ears. At first glance, it seems that the political opponents have finally decided to compromise on politics for once, for the betterment of the citizens of Karachi. But the devil is always in the details.

Before this grand transformation plan can be executed, there are two critical questions that need to be answered: who will pick the tab for the promised development, and who will get to spend this money and how. The answer to the first question is rooted in the political economy of Karachi, while the second is about fixing the broken and fragmented governance framework for this sinking metropolis.

Who will pay for the Karachi Transformation Plan? A question of political economy

PM’s announcement of the Karachi Transformation Plan conspicuously missed the respective contributions from the center and Sindh. No wonder that within 24 hours of the announcement, the cracks between the PTI and PPP started to appear.

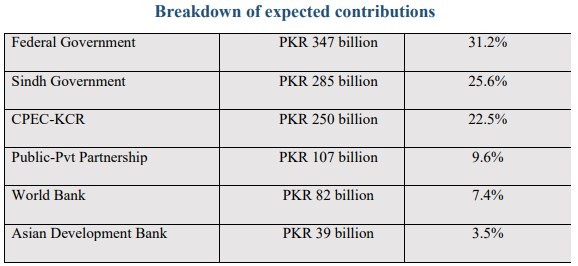

On the one hand, Asad Umar claimed that the federal government would be bearing 62 per cent share of the promised Rs. 1.1 trillion package, which amounts to Rs. 682 billion, but on the other, Sindh claimed that the provincial government is expected to pay the massive sum of Rs750 billion, leaving only Rs350 billion as the federal government’s share. The truth lies somewhere in between.

Read more: Pakistan’s Age of Accountability: Will it sustain itself?

The discrepancy stems from claims over the Karachi Circular Railway project, with both the center and province clamoring for it to be a part of their pot. Yet the bulk of the funds are expected to come neither from Islamabad nor Karachi, but from China under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

Even more interestingly, besides KCR, there remains a massive Rs. 366 billion amount that is unfunded. For now, both the federal and provincial governments have parked it under the public-private partnership model to balloon the package amount.

But the actual plans to mobilize this massive private sector financing are unclear, with little to show on the ground. For an investment of this scale, both the center and the province need a solid pipeline of projects with bankable feasibilities, which could take years, before these could be offered to the market.

If PTI could bring this transformation plan to life, it may be in for a long inning. But without addressing the political economy questions and working on a single unified governance structure, transformation of Karachi will remain a distant dream

But this blame game and bickering over-contribution versus claiming the credit is not new. Karachi remains a stepchild for Sindh for years, with the reins of the province in the hands of PPP, while the city falling under the control of MQM. There was hardly any political mileage for PPP to gain by investing in Karachi and therefore, PPP’s rule in Sindh has left little room or resources for the local governments to function effectively.

Karachi being the bastion of MQM, has been getting peanuts, even though it contributes 12-15 per cent to the national GDP. Over the next ten years, the city is expected to contribute $330-450 billion to the country’s economy.

As per World Bank estimates the city needs around $9-10 billion over the same period to finance its infrastructure and service delivery needs. This means that even if we plough back 2-3% of what the city contributes to the economy, it can be rescued. But misaligned incentives have so far prevented this.

Read More: Is PTI responsible for Pakistan’s economic mess?

Moreover, resource crunch also stands in the way of funding the development ambitions for Karachi. Sindh has an annual development outlay of merely Rs170b, while the federal public sector development program is Rs650b. Even if both the federal and provincial governments, along with development partners, pick the tab for Karachi’s transformation, they are likely to take years and will have to compromise on other constituencies craving for resources.

Who will spend the funds for Karachi Transformation Plan and how? A question of broken and fragmented governance structure

Then comes the issue of governance. Across the world, there are many models followed to govern large cities, ranging from mayor-council structure to city commissions and professional city managers. But nowhere in the world is there as fragmented a structure as witnessed in Karachi. Although on paper the city is managed by Karachi Metropolitan Corporation headed by the mayor, there are scores of other agencies and entities diluting KMC’s authority.

These range from six district municipal corporations with limited control of KMC, six cantonment boards, Karachi District Council and its 38 rural union councils, Karachi Development Authority, Malir Development Authority, Lyari Development Authority, Karachi Water and Sewerage Board, Sindh Solid Waste Management Board, Sindh Building Control Authority and more. Everyone is keen to assert their jurisdiction when it’s time to collect the rents, but no one is there to assume responsibility when it’s time for accountability.

This fragmented structure has been the primary reason that no development plan has ever been successful in Karachi. Therefore, even if the financing is arranged for changing the destiny of the city of Quaid, the implementation issues are likely to stand in the way of smooth execution.

Read more: ‘Best of times, worst of times’: PTI government completes two-year economic recovery

If there was ever a time for turning Karachi around, it may be now, with the PTI emerging as a legitimate political contestant for the city. If PTI could bring this transformation plan to life, it may be in for a long inning. But without addressing the political economy questions and working on a single unified governance structure, transformation of Karachi will remain a distant dream.

The writer is a public policy expert and an honorary Fellow of Consortium for Development Policy Research. He tweets at @hasaankhawar. A shorter version of this article originally appeared in Express Tribune on 8th September, 2020.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Village Space.