‘Pakistan has continued to suffer from inadequate capacity and other constraints, leading to large and frequent blackouts. At the heart of the impasse is the so-called “circular debt” crisis, whereby distribution utilities struggling to collect revenues and meet regulatory targets for transmission and distribution losses default on their payments to generators, and the sector is periodically bailed out by the government once losses accumulate to intolerable levels, at high cost to the exchequer.

This dynamic has undermined incentives for utilities to improve their efficiency, while discouraging generators from investing in new capacity to address supply shortages. In the meantime, little has been done to accelerate access to electricity to the significant share of unserved population in rural areas.’ Learning from power sector reform: the case of Pakistan.’ Robert Bacon (2019)

The excerpt indicates the issues underlying the power crisis in Pakistan. In the 1960s, the construction of dams put the country in the right direction of utilizing its ample water resources to produce clean and cheap hydroelectricity. Yet, the policy went into cold storage, not much work was undertaken after the construction of a few major dams.

Negative effects of this are observed even beyond the realm of the power sector, in the form of frequent, and at times severe flooding in the monsoon season, and reduction in the supply of water during the winter season, especially for agriculture and power sectors.

The focus of national policy shifted to more expensive and less environment-friendly options of producing energy, where the increasing demand for electricity was met with non-hydroelectric options, primarily in the shape of thermal electricity.

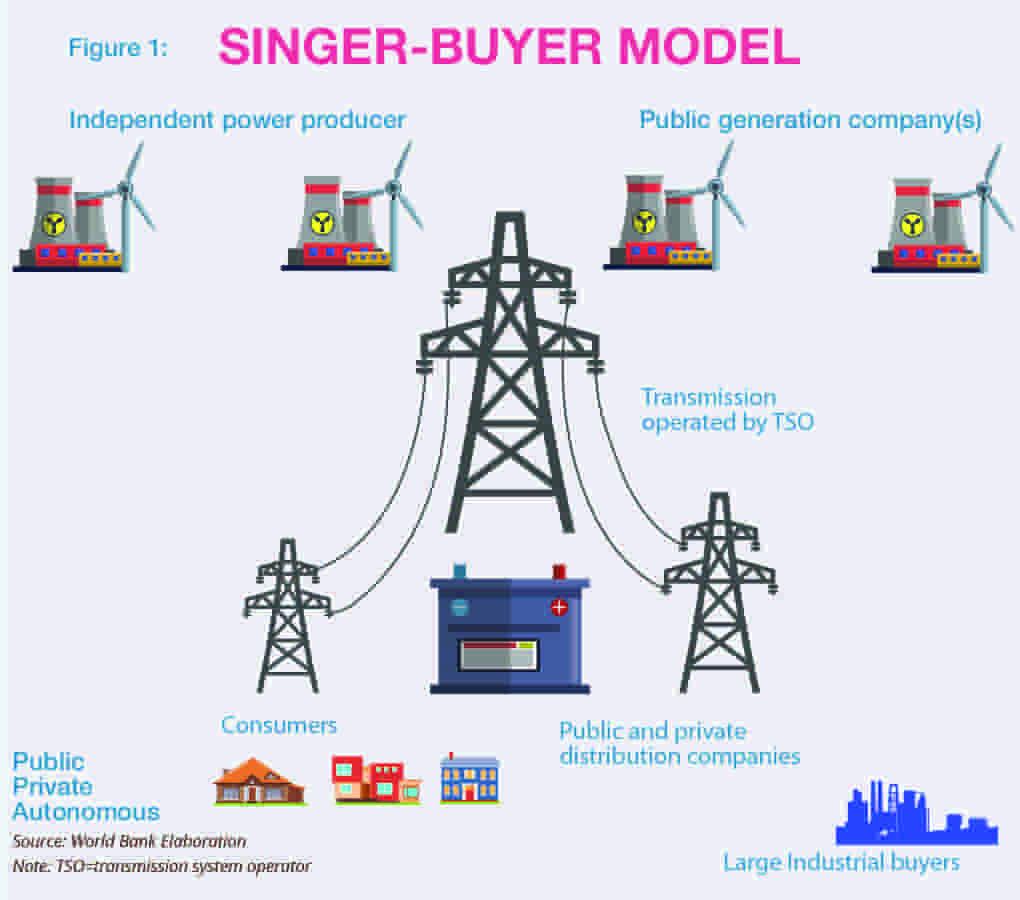

Hence, the usage of fuel-based sources and coal increased significantly over time, and with it came the burden on foreign exchange reserves. Currently, the power sector works on a ‘single-buyer model’, which can be understood through illustration Figure 1.

The Single Buy-out Model

The single buyer model has several errors, as highlighted by Leszlo Lovei (2000), ‘The Single-Buyer Model’ published in the World Bank Group’s document ‘Public policy for the private sector’.

Highlighted in the document, ‘many Asian, African, and Eastern European countries freeing up their electricity markets are preserving an artificial monopoly over the wholesale trading of electricity even after the vertically integrated national power company is unbundled.

Read more: Through Ebbs & Flows: The Political Journey of PTI & Its Current Challenges

The evidence so far suggests that this “single-buyer” model has major disadvantages in developing countries: it invites corruption, weakens payment discipline, and imposes large contingent liabilities on the government.

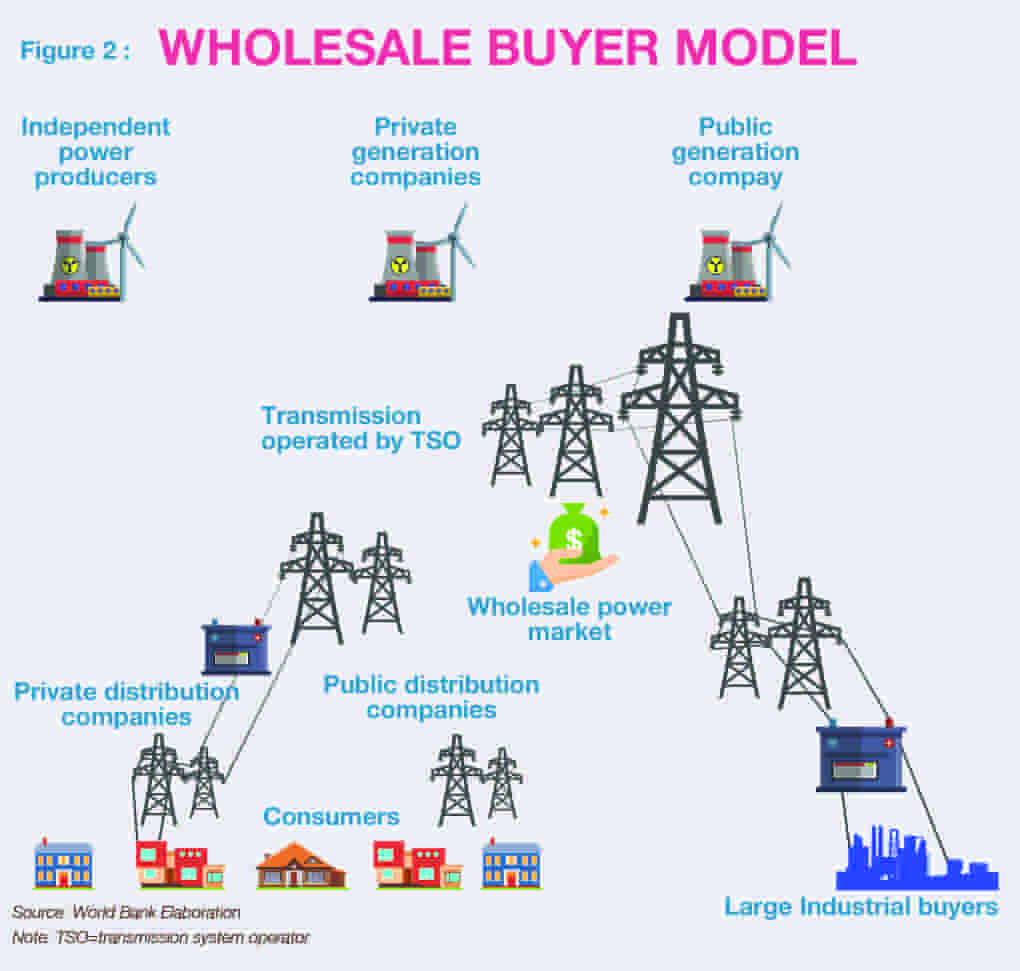

These disadvantages in most cases overshadow the higher short-term costs of a “bilateral contracts model” where generators contract with customers.’ Thus, there is a need to move towards a more competitive model, in the shape of the ‘wholesale-buyer model’ in Figure 2.

In the single-buyer model, ‘the distribution and transmission are separate businesses but the majority are state-owned, [while] a wholesale market exists for buyers (large industriesand distribution companies) to purchase power from a mix of public and private generators. The wholesale buyers can also purchase directly from generators. Distribution is a mix of public and private ownership.

The transmission network is operated by an independent transmission system operator.’ Hence, the wholesale-buyer model is better than the single-buyer model, since it removes most of the disadvantages of the single-buyer model by ‘allowing generators to sell electricity directly to distributors and large consumers.’ This will indeed bring much-needed competition and options in the power sector.

Read more: A Reform Agenda for State-Owned Enterprises in Pakistan

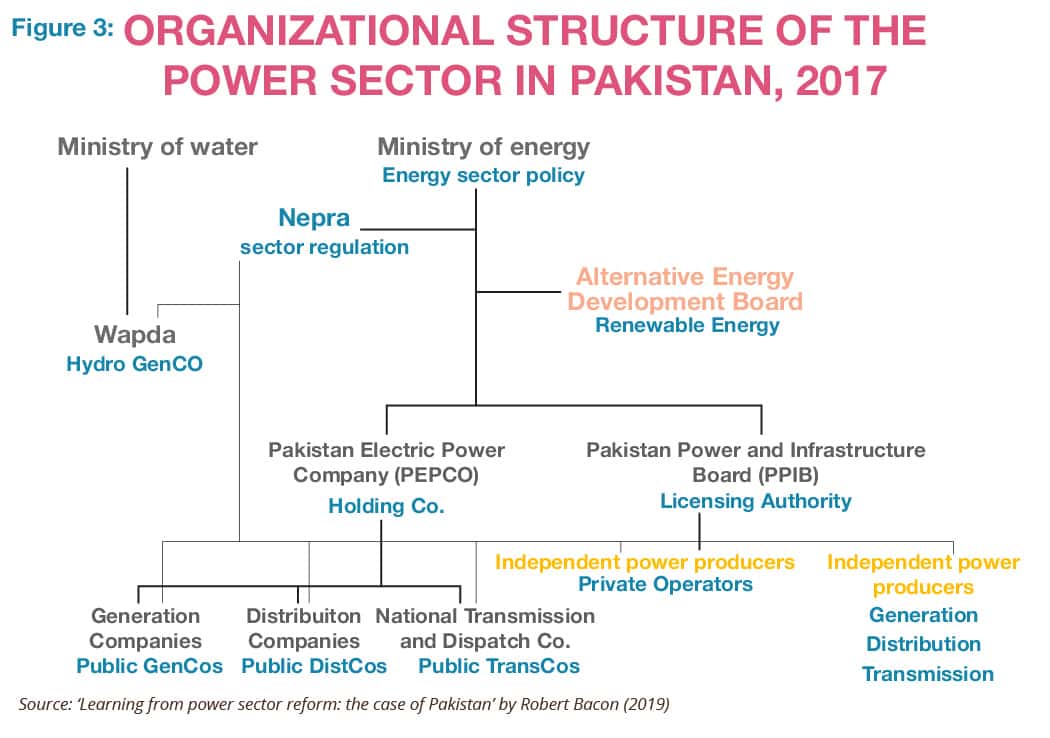

Simultaneously, along with the primary issues, the energy-related infrastructure was not upgraded, which increased the transmission losses in the system. The lack of reform in the institutional capacity meant that the recovery of cost diminished over time. This drop in the efficiency of the power sector utilities pushed the government to consider involving the private sector.

However, private sector inclusion has still been limited, and many unresolved issues about the performance of the private sector remain. Overall, it can be said that the reform efforts have been slow-moving. Currently, the power sector of Pakistan can be illustrated as in Figure 3.

According to a World Bank Group’s policy research working paper by Robert Bacon (2019), it states, ‘At the beginning of the1990s Pakistan had a vertically integrated national power system. It first endorsed a sector reform program in 1992, following a period of severe power shortages, and in 1994, IPPs were allowed to enter the sector, which they did by adding 4,500 MW.

However, the planned step to unbundle the sector took six years to happen and only two of these unbundled companies have been privatized until now, despite a further strong commitment to do so by the incoming government in 2013.

The thermal Kot Addu Power Plant was partially privatized in 1996 with a further sale of some of the government shareholding in 2005, and the one full privatization that did occur was of the historically separated vertically integrated Karachi Electric Supply Company (now referred to as K-Electric – KE).

Read more: Stagflation and it’s prevalence in Pakistan

A regulatory authority (NEPRA, or National Electric Power Regulatory Authority) was established in 1997, but tariff setting for consumers was retained by the government.’

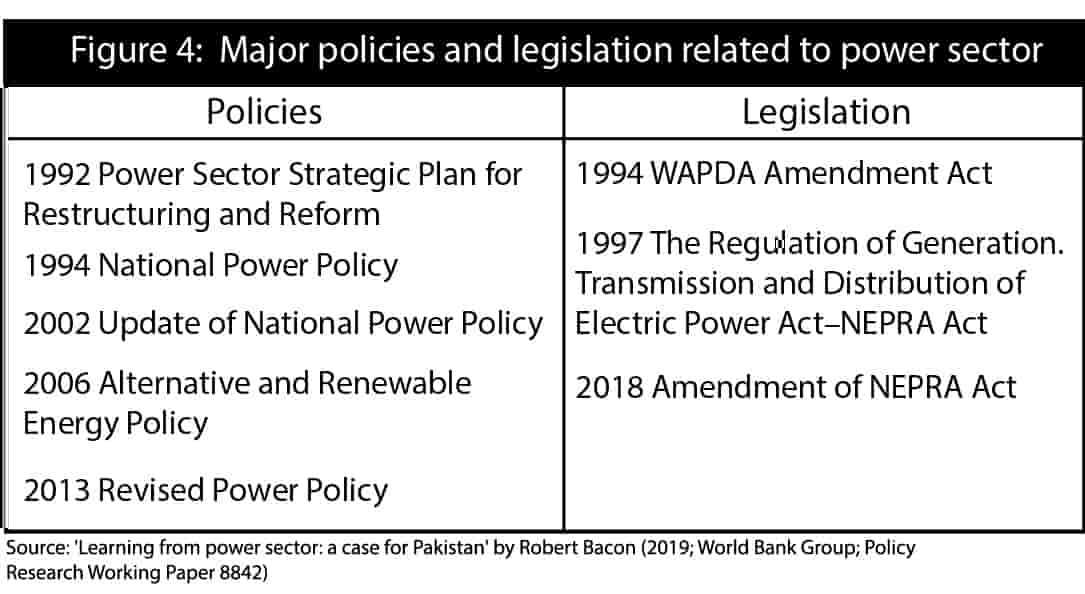

Moreover, Figure 4, highlights the main policy reports and legislations regarding the power sector during 1992 – 2017. This slow-paced reform process meant that the gap between electricity supply and demand increased over time, resulting in electricity shortages and power cuts.

At the same time, the lack of institutional capacity, production of electricity through more expensive options, weak control over corruption, and the slack of subsequent governments to recover bills from the population, all meant that the power sector could not fully recover operational costs.

These factors resulted in frequent and costlier government bailouts to the sector to satiate the phenomenon of ‘circular debt’. According to a recent Business Recorder report, the circular debt had ballooned close to Rs. 1.9 trillion (more precisely, Rs. 1.8842 trillion) as of the end-January 2020.

This indeed is a huge drain on the exchequer. The concerning part is that PTI is the third government in power (after PML-N, and PPP, respectively, since 2008) that is struggling to deal with resolving the issue of circular debt, that has seen only lukewarm reforms in the power sector.

Read more: Complex Kaleidoscope of Pakistan’s political theatre

Though, in 2011, the circular debt heavily affected the power sector with IPPs (independent power producers) threatening to call-in sovereign guarantees, the current level of circular debt has reached unprecedented levels. The situation has worsened over time, and its continual bailout cost remains one of the main causes of the fiscal deficit, which the country often finds itself in.

Increasing Tariffs? The dilemma

Apart from using taxpayer’s money to bail out the power sector because of inefficiency – both within the public sector and the private sector– the other tool employed is thevirtually continuous increase in power tariffs.

This has made it costly for households as well as businesses to use electricity. Therefore, contributing in turn to in-action overall, and significantly playing a role in making exports less competitive.

What causes Circular Debt?

The breakdown of the issue of circular debt highlights the following important determinants:

- Unpaid bills by the consumers remain a basic source of the debt.

- Decision by the government to hold prices charged by DISCOs (distribution companies) lesser than the NEPRA determined cost recovery tariff.

- Delays generally in tariff determination and notification. ‘The tariff setting formula used by NEPRA to calculate cost-recovery tariffs. Including an allowance for “normal” transmission and distribution (T&D) losses. To the extent that actual losses were greater than allowed losses.

- Thus, the excess contributed to circular debt. In 2012, five of the nine DISCOs had actual losses exceeding allowed losses by more than 3 percentage points,’ (Robert Bacon; same article), and

- ‘The fuel price adjustments are caused by delaying adjustments to monthly fuel price changes in the formula used to calculate tariffs.’ (Robert Bacon). The story of power sector reforms in Pakistan could be further understood through analyzing the extent of reform that actually materialized.

There are also some privatized utilities facing difficult operating environments (such as in the Pakistani city of Karachi or the Indian state of Odisha) that perform no better than some of the worst public utilities

In the World Bank Group’s report (2020), ‘Rethinking power sector reform in the developing world’ highlights, for instance, Pakistan in 2015, showed that reforms announced were around 20 percent higher than actual reforms delivered. This is a steeper gap than many other countries of similar economic conditions.

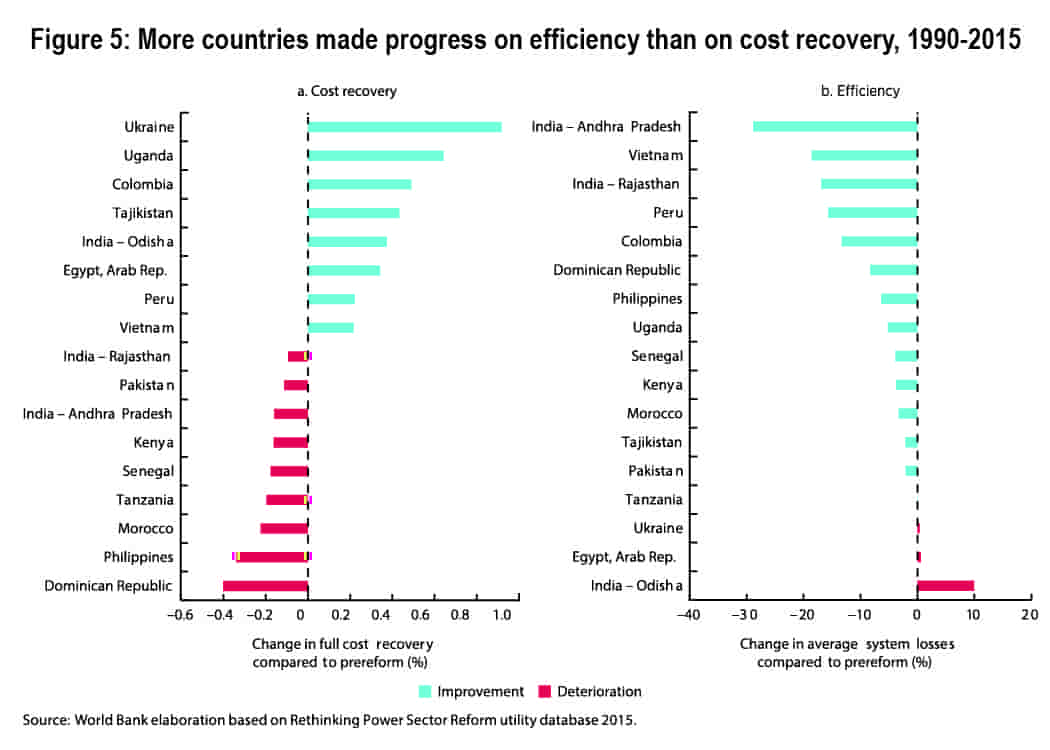

The Philippines, for example, the comparable number is less than 5 percent difference in the adoption of reforms announced and delivered. The same report highlights that in the example of countries taken, (see figure 5), it can be seen that in the case of Pakistan, in terms of cost recovery, the situation has worsened throughout 1990-2015.

While at the same time, as a positive sign, ‘average system losses’ or inefficiency slightly decreased. Albeit, unlike many other countries in the sample, such a reduction in system losses was quite low.

Overcoming the Crises

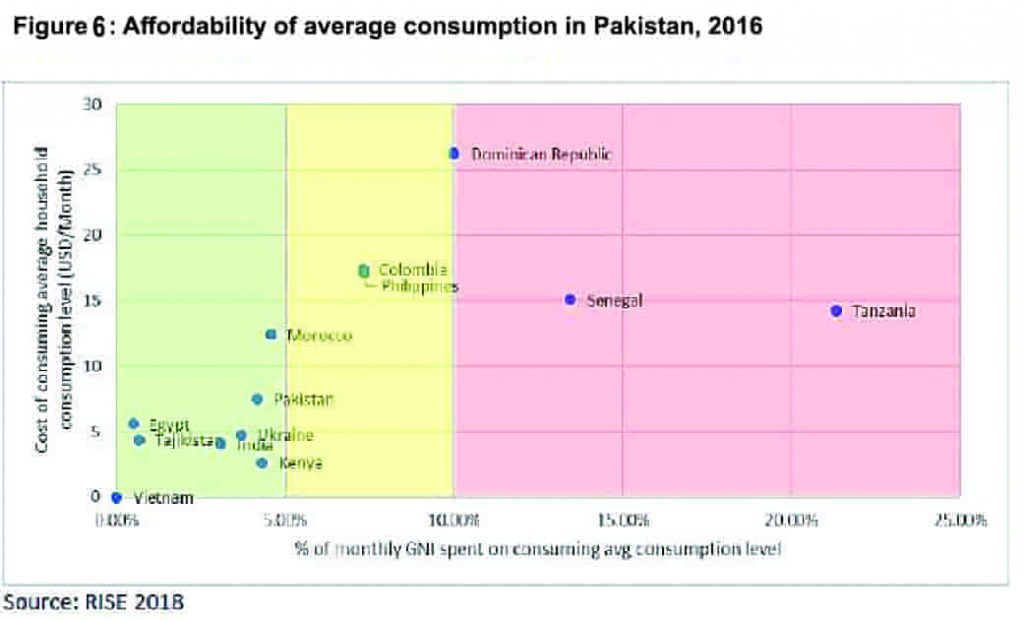

Pakistan needs to improve the affordability aspect of power purchases for consumers, where according to a World Bank study (highlighted in Figure 6) ‘in Pakistan, to purchasethe average amount of electricity the bottom 40 percent of households would have to use 4.18 percent of their income, bringing it just under the acceptable level of 5 percent.’

Hence, the government needs to understand the gravity of the situation faced by the power sector, and its consequences for the economy at large. For long the consumers and manufacturers of this country, have suffered at the hands of lacking motivation of the government to effectively reform the power sector, and not just rely on tariff increases and bailouts.

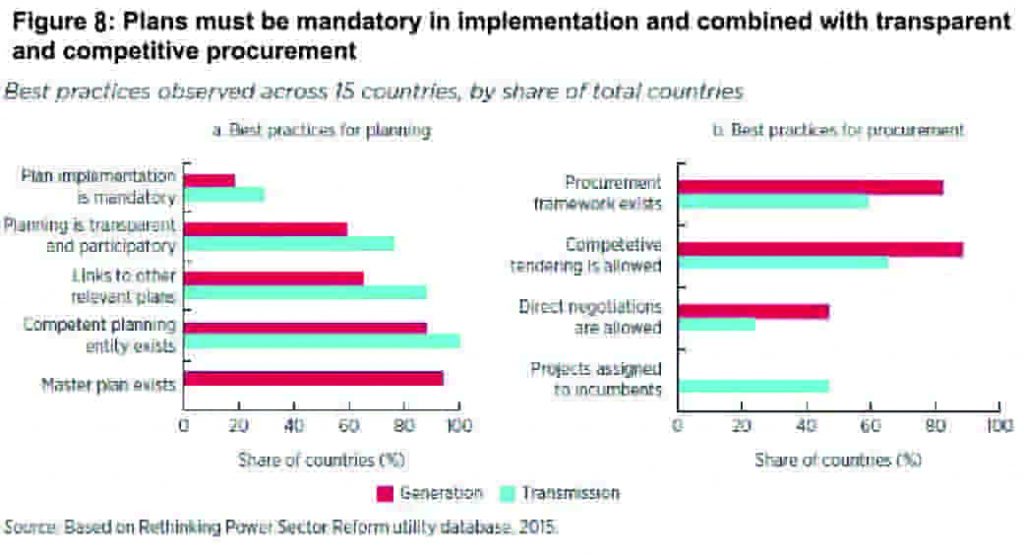

Moving forward, Pakistan needs to give proper attention to the function of power sector planning. In this regard, ‘The institutional responsibility for planning needs to be assigned to an entity with adequate technical capacity.

A wide range ofinstitutional arrangements for power systems’ planning can be observed across countries. Most prevalent are cases where the planning function is assigned either to the line ministry or to the power utility; in some cases, it is assigned to both.

For sectors that are unbundled, it is the transmission utility that may retain the sector planning function (as in Egypt and Pakistan), and once competitive markets are introduced this responsibility may migrate to the system operator (as in Ukraine).’

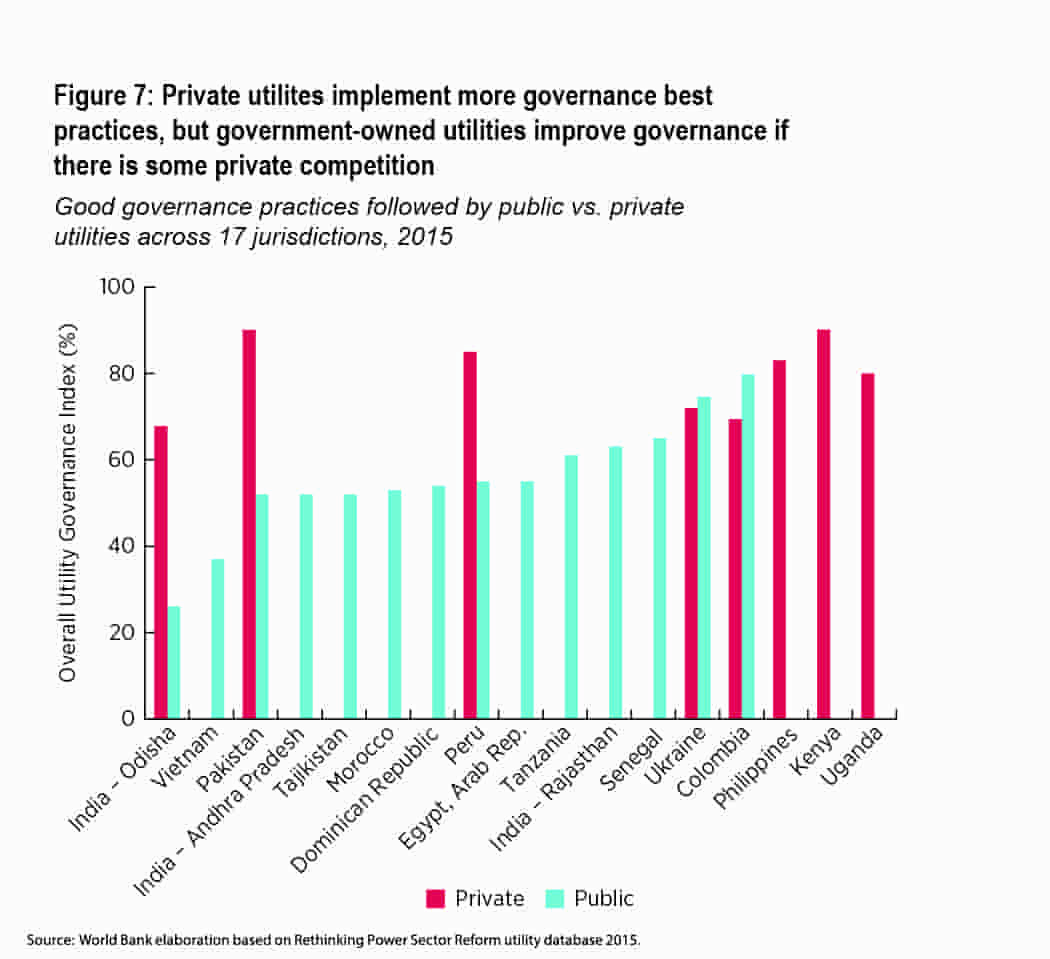

In Pakistan, it can be seen that in terms of both generation and transmission, sector planning needs to improve drastically. Moreover, there is a dire need to improve the corporate governance element of the power sector.

There is a utility governance index, which ‘measures the extent to which specific utilities conform to good practices.’ The utility governance index rating is around 50 percent for public sector utilities for Pakistan – which is the main player in the power sector.

To Exist and Persist

Overall, Pakistan up till now has mainly unbundled its power sector vertically. Privatization is only to the extent of K-Electric, which too suffers from several issues.

It is highlighted by World Bank in the report (2020) ‘Rethinking power sector reform in the developing world’ whereby it is highlighted ‘in Pakistan, for example, the unbundled power sector has been plagued by a chronic circular-debt crisis that undermines the payment chain; the only privatization in the distribution sector continues to be disputed in the courts after more than a decade of litigation…

Read more: Locking down the Essentials: Whilst Hoping to Survive

There are also some privatized utilities facing difficult operating environments (such as in the Pakistani city of Karachi or the Indian state of Odisha) that perform no better than some of the worst public utilities.’

Hence, the unbundling needs to be augmented with other reforms, including the ones being suggested here. This would change the entire perception of the sector and a significantly different approach will be incorporated to deal with the matter systematically.

Dr. Omer Javed is an institutional political economist, who previously worked at International Monetary Fund, and holds Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Barcelona. He tweets at @omerjaved7.

The views expressed in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Village Space.