Pakistan is expected to ‘run dry’ by 2025 and according to a recent IMF report, the country is ranked third in the world among countries facing acute water shortages. By 2040 it will be the most water-stressed country in South Asia.

To make matters worse Pakistan has the world’s fourth-highest rate of water use. Its water intensity rate, which is the amount of water, in cubic meters (m3 ), used per unit of GDP — is the world’s highest. Pakistanis will become water insecure very soon if no action is taken.

This means they will not have access to safe and affordable water to satisfy their needs for drinking, washing or their livelihoods. The water scarcity of a country can be measured by four indicators (i) Falkenmark indicator (ii) Water Resources Vulnerability Index (WRVI) (iii) IWMI’s Physical and Economic Water Scarcity Indicators and (iv) Water Poverty Index (WPI).

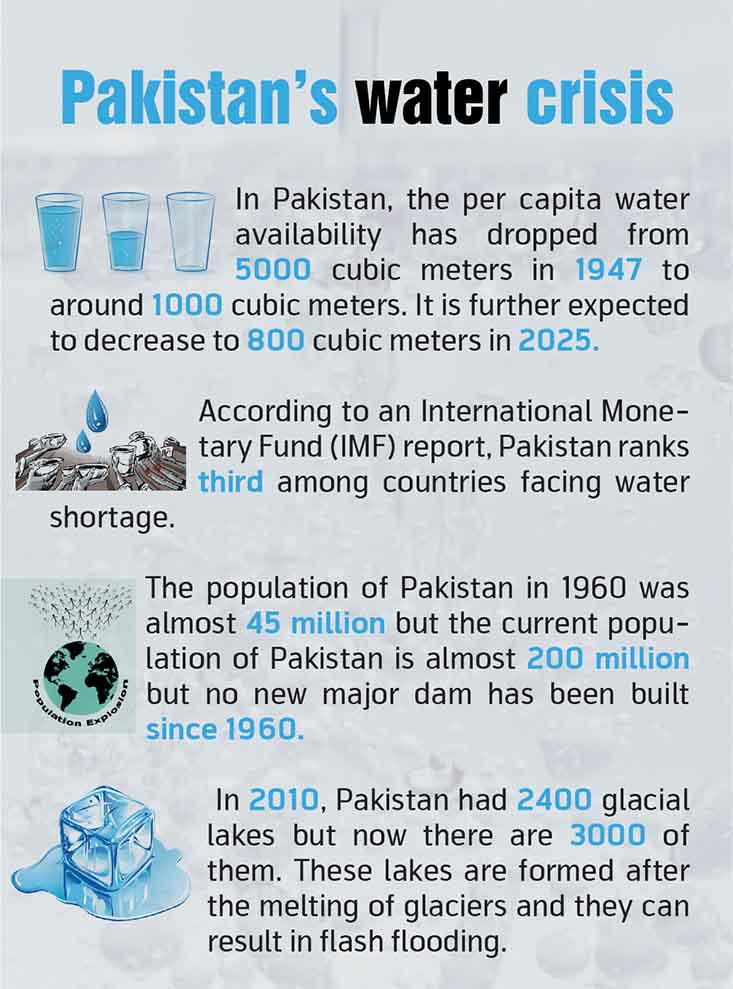

The Falkenmark Indicator provides a relationship between the available water and the human population. Countries that have per capita water resources less than 1700m3 are said to be water-stressed and those below 1000m3 are called water-scarce countries. However, when per capita water availability falls below 500m3, the country experiences an absolute water scarcity. In 1951, per capita water availability in Pakistan was over 5260m3.

Pakistan touched the water-stress line in 1990 and it crossed the water-scarcity line in 2005. Presently per capita water availability is around 903m3 and under the present conditions, its per capita availability of water is expected to drop to 787m3 in 2025 unless new water reservoirs are built.

Presently per capita water availability is around 903m3 and under the present conditions, its per capita availability of water is expected to drop to 787m3 in 2025 unless new water reservoirs are built.

Over the past seven decades, the population has increased manifold while corresponding water storage capacity has not. Conservative projections show that the population will be 227 million by 2025. The country is fast moving towards Absolute Water Scarcity. Water Resources Vulnerability Index (WRVI) compares national annual water availability with the total annual withdrawals (percentage).

If annual withdrawals are between 20-40% of the annual water supply, the country is said to be water scarce. If it exceeds 40%, the country is said to be severe water scarce. In Pakistan, the total water available is 263 billion m3 of which surface water is around 190bm3 and groundwater is about 73bm3. The total surface water used is about 140bm3 and groundwater used about 62bm3. The total water used is about 202bm3.

Read more: Water scarcity making country a wasteland

Pakistan’s Water Vulnerability Index is 77 percent against a standard withdrawal of 20%. Physical and Economic Water Scarcity Indicators are framed by the International Water Management Institute. According to these indicators, a country that will not be able to meet the estimated water demand in 2025, even after accounting for the future adaptive capacity, is called “physically water scarce”.

A country that has sufficient renewable resources but would have to make a significant investment in water infrastructure to make these resources available to the people is called “economically water scarce”. In Pakistan, water shortfall was 11% in 2004 and will increase to 31% by 2025. Due to this shortage of water and increase in population, there will be food shortfall of about 70 million tons by 2025.

Since Pakistan has to make significant efforts and investment to meet the water shortage, therefore, it is both physically and economically water-scarce country. Water Poverty Index (WPI) has five components: (i) Access to water (ii) Water quantity, quality and variability (iii) Water uses for domestic, food and productive purposes (iv) Capacity for water management and (v) Environmental aspects.

According to the WPI, if water is available but is of poor quality, the country is still a water scarce country. The Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR) implemented a series of national surveys (2002-2006) to monitor drinking water quality in 24 major cities of Pakistan and found more than 80% samples unsafe for human consumption.

Pakistan gets 80% of its water during the 90-120 days period (June to September). But in the absence of enough storage capacity, on an average 32MAF of water per year drains off into the Arabian Sea.

Another survey was carried out in rural areas of Pakistan from 2004 to 2011. Out of 14,000 drinking water samples, 82% were found unsafe. Over 10,000 existing water supply schemes were also surveyed from 2006 to 2012 in the four provinces including Gilgit Baltistan and Azad Jammu & Kashmir. Only 23% in urban and 14% in rural areas were providing safe drinking water.

Pakistan Vision 2025 set a target to ensure clean drinking water to all Pakistanis by 2025. During the past years, many efforts were made by the government for the provision of safe drinking water to the masses. But the intended objectives could not be met. According to the indicators discussed above, Pakistan is now a water-scarce country.

Read more: Water scarcity in Pakistan

Wasting Precious Water Resources Due to Inadequate Storage

One of the major reasons of water scarcity is inadequate storage. The per capita water storage of Pakistan is far less as compared to other countries. The per capita water storage of Australia and USA is over 5000m3, China 2200m3, Egypt 2362m3, Turkey 1402m3, Iran 492m3, India 225m3, while in Pakistan it is 159m3.

The storage capacity of Egypt is 1000 days, USA 900 days, South Africa 500 days, India 220 days and Pakistan only of 30 days against the basic requirement of 120 days. The present water storage capacity of the country’s three major reservoirs is only 9% of the average annual inflow, against the world average of 40%.

Due to sedimentation in the reservoirs, the capacity is being lost at a rate of 0.27bm3 per year. By 2010 the reservoirs had already lost about 8.1bm3 of their storage capacity. Falling within the monsoon range, Pakistan gets 80% of its water during the 90-120 days period (June to September). But in the absence of enough storage capacity, on an average 32MAF of water per year drains off into the Arabian Sea.

Similarly, Pakistan loses 50% of its water due to inefficient water management. In order to eliminate 32MAF water losses, large storage dams need to be built on a priority basis on approved sites. Due to inadequate storage, Pakistan wasted over 120 bm3 of water during the floods of 2010, 2012 and 2014, this loss was in addition to the devastating effects the floods had on infrastructure, crops, livestock and human beings.

Currently, out of 77MA cultivable land, about 55MA land is being cultivated as irrigated and Barani area, whereas 22MA land is still available for agriculture, subject to availability of water. To sustain the agricultural economy as well as ensure national food self-sufficiency through the mainstay of IBIS, the minimum additional storage requirement by 2025 would be 18MAF (22BCM).

As a part of the Indus Basin Settlement Plan, three Reservoirs were built by 1976 at Mangla, Chashma, and Tarbela for storage and regulation of Indus water and Jhelum River flows. These reservoirs provided a live storage capacity of 15.75MAF which was destined to deplete due to sediment deposition. The planning in the 1960s was that Pakistan would progressively build additional reservoirs to compensate for sedimentation losses and to meet additional needs of development.

Kalabagh is by far the most suitable site for water storage, both on considerations of hydrology and power evacuation. The inflows at Kalabagh are more than any other upstream site and its location is closest to the national power grid systems requires minimum transmission lines

World Bank in its 1967 report on “Study of the water and power resources of West Pakistan” had recommended building a large size reservoir every decade for the foreseeable future. As such, during last four decades, Pakistan would have added about 24 MAF of storage capacity. Pakistan failed in this regard. On Indus there are only four sites namely Kalabagh, Bhasha, Skardu and Yogo on its Shyok tributary.

The sites of Kalabagh and Skardu have environmental and political problems of special significance. The Diamer-Bhasha dam which has 8.5 MAF live capacity, after completion of design and tenders, is ready for implementation and the Supreme Court has also ordered and rightly taken initiative for its work. The previous federal government had approved the project in August 2009 at a cost of $12 billion.

Read more: Muslim countries to face severe water scarcity by 2025

Implementation activities of the main project were scheduled to commence in 2009-10 and reach completion in 2020-21 but did not commence due to non-arrangement of foreign funding. Implementation of the main project has been divided into five lots with an updated cost of now around $14 billion. Bhasha dam will be large storage and powerful machine.

Shyok dam, located 3 km upstream of Khaplu, can store 5.6MAF of water with very little environmental impact. Skardu dam, with a storage capacity of more than 20 MAF, as was envisaged in the sixties, now would not be undertaken due to huge environmental impact. However, a lower dam with 2 to 3 MAF capacity can be studied and built on the same site.

The dams at Shyok and Skardu would be beneficial in reducing the sedimentation load at downstream sites. Particularly life of Bunji dam and its power units would be greatly enhanced. However, Kalabagh is by far the most suitable site for water storage, both on considerations of hydrology and power evacuation.

The inflows at Kalabagh are more than any other upstream site and its location is closest to the national power grid systems requires minimum transmission lines. Major objections are its environmental and political impacts which can be resolved by serious interaction and consultations with the stakeholders.

The best option would be to build the project according to the Planning Report of June 1988. KP reservations on this report can be addressed by reviewing the maximum conservation level. The concerns of Sindh can be alleviated by discussing and agreeing on reservoir operation rules.

Once it is accepted that Kalabagh may have storage of about 6 MAF, the next crucial point is how and when to store water and how to release it for maximizing its benefits to the irrigated areas, the riverine areas (Kacho) and the Indus delta areas. The hydrology of Indus River shows that a very large flood occurs every five to ten years.

The reservoir at Kalabagh can help to chamfer the flood peak and later utilize the stored water for environmental flows. A carryover dam, if built at Kalabagh site, can normally be operated as a run of the river project with conservation level (at the minimum pool level) given in the 1988 project report. Thus, it will generally be producing electricity at this low head.

Read more: Scarcity of Life: Water shortages reaching vertical limits in Pakistan

During every super flood its carry overcapacity can be utilized to reduce the flood peak and alleviate flood damages in Punjab and Sindh. In subsequent times, at well-designed intervals, this stored water can be sent down in stages to meet the environmental needs of the Indus delta. Pakistan urgently needs to look into the possibilities of development of water sources including enhancement of water storage capacity, control over conveyance losses, and efficient use of water resources for agriculture, industrial and domestic purposes.

The planning in the 1960s was that Pakistan would progressively build additional reservoirs to compensate for sedimentation losses and to meet additional needs of development.

Also, preventive measures are needed against floods both to reduce damages and to use the floodwaters. Initiatives need to be taken to recharge groundwater in water-stressed areas on a priority basis before the country reaches an absolute water scarcity situation. An urgent comprehensive plan should be made for the maintenance and improvement of the existing infrastructure to minimize water losses/wastage, and for harvesting rainwater including:

a) The lining of canals and water channels: To avoid or minimize conveyance losses of around 10 MAF, it is necessary that canals and water channels are lined. This will also help in improving the supply of water to tail-end users thus increasing agricultural productivity.

b) Farm Water Management: Proper levelling of land and application of appropriate water management techniques (such as drip/trickle and sprinkle irrigation systems) can save a substantial quantity of water which should be used for bringing additional available land under cultivation. Although the initial cost of installation of these systems is high, the benefits in terms of water resource management are also high.

c) Rainwater harvesting: Huge quantity of water generated through torrential rains should be harnessed, through watershed management and small/delayed dams, instead of allowing it to turn into floods causing damages to life and property.

d) Groundwater management: Since the groundwater situation is not even across the country, as some parts are surplus in water whereas the others are deficient, so region-based policies should be formulated to address the issue. Installation of tube-wells should be encouraged in water surplus areas to avoid degradation of land and water mining be discouraged in water-deficient areas.

Read more: Pakistan facing ‘absolute scarcity’ of water: Severe implications

e) Reusing wastewater: Sufficient quantity of water can be reused by application of treatment technology as done in South Korea, where 6.4 billion tons sewerage water /year is treated for cleaning, washing and cooling purposes. This will not only help improve water availability but also facilitate in arresting water pollution.

f) Creating the correct policy and regulatory framework: Proper legal and regulatory framework for water needs to be formulated at the government level. In view of the importance of water for human existence and the fact that it is a finite resource and the externalities involved in its use or misuse warrant for framing state regulation.

Accordingly, water should be declared a national asset so as the ownership of surface and groundwater rests with the state. Secondly, there is the need for an independent regulating body, especially at provincial level. Presently, there is no independent regulator making regulations or policies for water resource management and planning. So it is necessary to assign value to water so that it should be used efficiently and effectively.

g) Water pricing to recover O&M cost: The existing water pricing is not adequate and it hardly covers 10-25% of the Operating & Maintenance (O&M) cost resulting in deterioration of services. There is a dire need to bring the service delivery system to a high equilibrium through pricing that recovers the O&M cost. The implementation of the same should be done in phases.

Saud Bin Ahsen is associated with a Public Policy Think Tank Institute and a Public Administration & Economics graduate from Punjab University & GCU Lahore. He is interested in Comparative Public Administration, Post-Colonial Literature, and South Asian Politics. He can be reached at saudzafar5@ gmail.com.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Village Space.