Totalitarian regimes do not afford to allow public intellectuals and free thinkers to express their ideas freely. The very composition of an authoritarian regime demands utmost protection and strong military to limit dissent for its survival. Controlled systems of governance become more problematic if they have been skillfully institutionalized under the cover of democracy. The available literature categorizes such states as competitive authoritarian regimes.

A democracy challenges the basic theoretical assumptions of authoritarianism and offers an alternative system of governance. Freedom of speech, free and fair elections and right to practice one’s religion without fear or humiliation are what essentially define a representative democracy in the 21st century. Unfortunately, democracy is under threat in the times of President Donald Trump and Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Freedom House reported in 2018 that democracy around the world was ‘under assault and in retreat’.

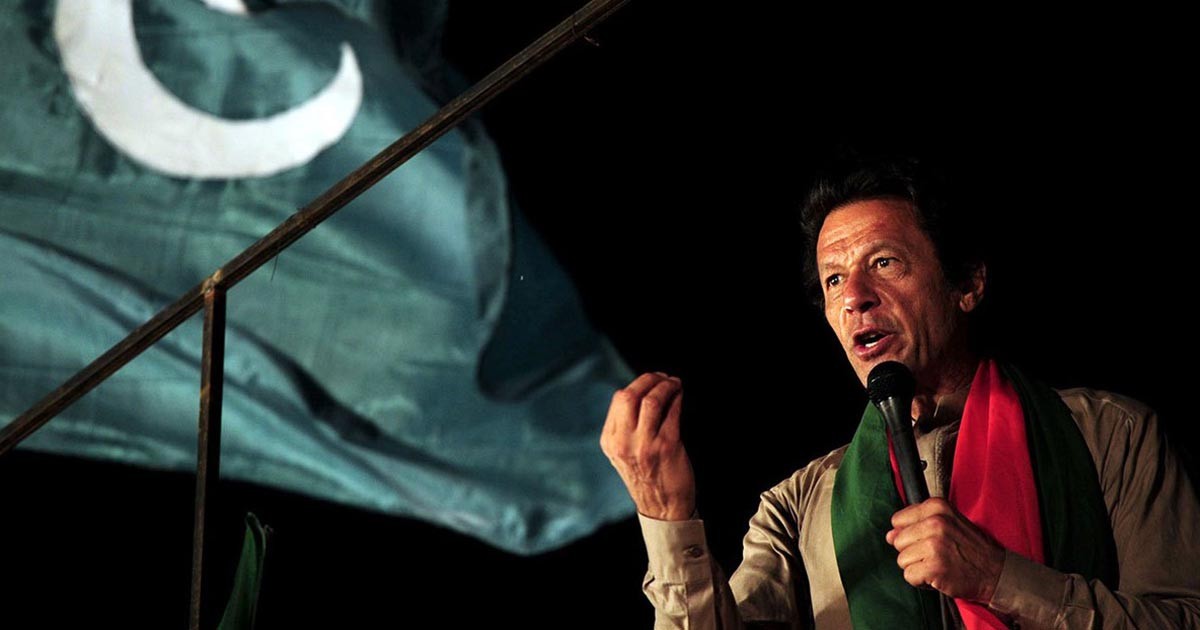

There are some reasons behind the government’s ill-thought policy of controlling social media and free flow of ideas. Firstly, Prime Minister Imran Khan’s government could not perform on economic front

The world is moving fast towards totalitarianism or competitive authoritarian regimes where democratic institutions exist but without democratic spirit. The most lethal weapon being used to defeat democracy is to control public opinion and suppress voices which attempt to challenge the status quo. Be it India or Pakistan, public intellectuals are facing unprecedented censorship for having politically disturbing ideas.

But the question is why do authoritarian regimes fear academics or bloggers? Judith Butler, professor of Comparative Literature and critical theory at the University of California at Berkeley, recently wrote an article and explained the situation. “What the authoritarian fears are that open discussion in a university seminar will move outside those walls. They are right to fear the circulation of ideas, which are unpredictable and uncontrollable.

And they are right to fear those ideas that contest the legitimacy of authoritarian rule, or fascism, or racist regimes, since once the unjust character of those regimes is openly demonstrated and discussed, once public life is given to those forms of intellectual critique, people may well identify and oppose unjust rule and rise up to demand the end to injustice,” she wrote.

Read more: 5th Gen. War: How Pakistani media played in the hands of enemy?

In Pakistan, there is an intense debate going on to ‘regulate’ social media which, from the government’s standpoint, has emerged to be a platform ‘above the law’. Every sane person in this country wants the government, opposition, public intellectuals and academics to sit together and formulate a comprehensive policy to regulate social media. However, the government seems to be politically motivated and intends to curb freedom everyone enjoys on digital platforms. This is, if anything, a dangerous trend.

There are some reasons behind the government’s ill-thought policy of controlling social media and free flow of ideas. Firstly, Prime Minister Imran Khan’s government could not perform on economic front. An ordinary citizen from far-flung areas is not interested in macroeconomic debates. He knows the fact that life for him has become miserable. The government, on the other hand, sheepishly demands empathy and ‘more time’ to deliver.

There is no sugar and wheat, and the people have been asked to be careful while criticizing the incumbent government. This is what may pave a way for mass mobilization against an authoritarian regime

Secondly, the PTI’s government in Punjab, Pakistan’s largest province, has disappointed everyone. PM Imran Khan promised to reform police, upgrade health and education sectors, and end corruption at any cost. One and half year has passed and nothing has changed. Punjab police and bureaucracy are unchanged. The provincial Health Minster seems to be nowhere. We last saw her when she shared some reports about former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s health.

Thirdly, Prime Minister Imran Khan seems to be politically confused if not completely helpless. He never wanted Nawaz Sharif to leave for London. He never wanted to be lenient with Asif Ali Zardari. But he had to do what he was asked to. Now he does not want media or anyone else to mock him for his political compulsions on national TV.

Apparently, these aforementioned reasons compelled the prime minister to advise his legal team to regulate media. The premier wants media, civil society and public intellectuals to be cooperative without questioning his infallible wisdom. He does not like to be questioned about Chief Minister Usman Buzdar’s performance, economic crisis or selective process of accountability. He just wants everyone to listen to him.

Read more: The beginning of the Bengal hybrid war

But there is a problem with PTI’s policy of controlling social media. They may be able to ensure that nobody questions anything. However, this may lead to public processions and anti-government protests across the country. There is no sugar and wheat, and the people have been asked to be careful while criticizing the incumbent government. This is what may pave a way for mass mobilization against an authoritarian regime.

This is moral responsibility of every concerned citizen to stand up against an authoritarian regime to protect the fundamental rights promised by the constitution of the land. Professor Butler rightly opines that public intellectuals and universities produce ideas that have a life of their own; the free circulation of those ideas is part of democratic political culture, and the protection of that circulation is an obligation of democratic societies.

Farah Adeed is an Assistant Editor in GVS. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Global Village Space’s Editorial Policy.