Yaqoob Bangash, an esteemed South Asian historian, argues that both India and Pakistan’s new maps are based on an erroneous understanding of what constitutes Gilgit-Baltistan. While it is not in Indian interest in the correct legal position or aspirations of people in the region, it is high time that Pakistan should recognize the correct position.

The dispute over the State of Jammu and Kashmir is one of the oldest yet of the least understood cases in the world. For some, it is a simple legal case of the accession of a princely state; for others, it’s a question between India and Pakistan. Still, others maintain that without the involvement of the people of the state, no solution would be acceptable.

One reason why the issue has been tied in several knots is the lack of understanding of the makeup of the state. For historical reasons, neither have the boundaries of the State of Jammu and Kashmir been clearly understood and nor have the regions which constitute part of the state been distinctly marked. This lack of understanding of the actual makeup of the state has created a lot of confusion over the years.

Read more: Kashmir, Gurdaspur & Mountbatten?

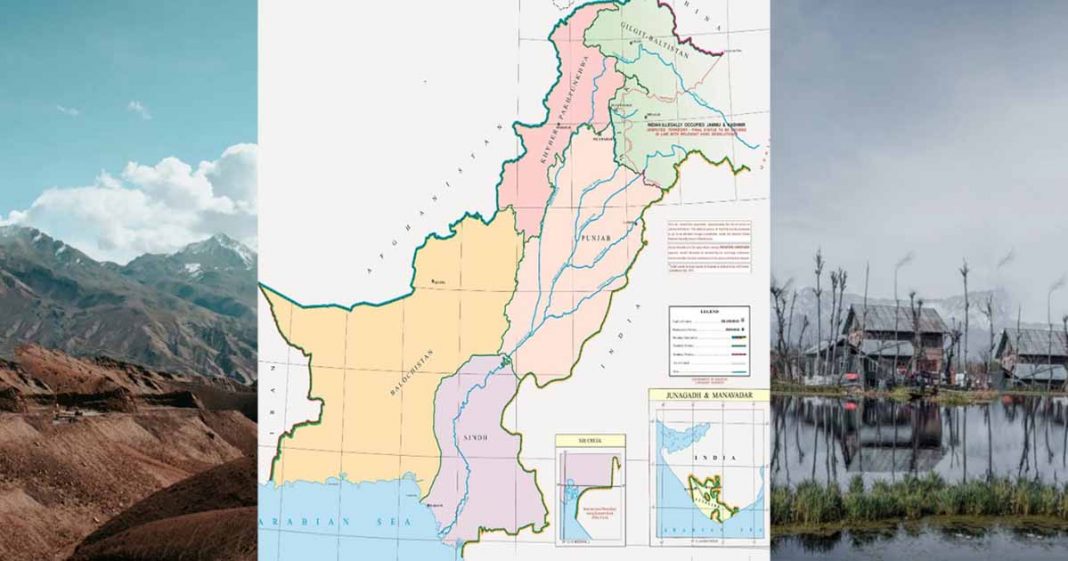

Between August 2019 and August 2020, India and Pakistan respectively, issued their own maps of the region, with both claiming territory controlled by the other, clearly showing the importance of the extent, borders and limits of the erstwhile state. However, both maps exhibit a lack of understanding of the actual makeup of the former state they are disputing, thus perpetuating some historical myths, and creating further confusion.

Great Game politics in Jammu & Kashmir

As is well known, the modern State of Jammu and Kashmir came into existence in 1846 under the Treaty of Amritsar under which the Dogra Raja of Jammu, Ghulab Singh, purchased Kashmir from the Sikh Durbar for seventy-five lakh rupees. This ‘sale,’ somewhat unprecedented in recent history, thus gave birth to one of the largest princely states in the British Indian Empire.

Subsequent expansion by successive Maharajas extended the borders of the state to Ladakh in the East, and Gilgit in the West, while in the north its borders just about met the Russian Empire. However, just as the Maharajas were keen to expand the boundaries of their new state, the British were also wary of this northern frontier.

The Government of Jammu and Kashmir obviously lay claim to the whole Agency and argued that if it agreed to the federation, not just the Gilgit Wazarat

The ‘Great Game’ had started, where the British were afraid that the Russians would attack India to get to the ‘warm waters’ of the Indian Ocean and thus efforts were made to check Russian advances. Britain’s relations with Afghanistan (and the wars with the country) then began to be conducted primarily through the lens of the Great Game, and forays by any state in the north of India had to confirm with the objectives of Russian containment and surveillance.

Thus, just a few years after the Kashmir Durbar captured Gilgit town in 1870, the Government of India sent Col. John Biddulph as an officer on special duty in 1877 for ‘protecting trade and watching over political events.’

After the death of Maharaja Ranbir Singh in 1885, the British were able to assert their control of the region even further.

Thus in 1889 a ‘Gilgit Agency’ was set up in what was the north, north-west of the state, directly responsible to the Government of India, under which a sort of a dyarchy emerged: the British were responsible for foreign affairs, defence and communication, while the Kashmir Durbar looked after the civil aspects of government.

Read more: Timeline: Where is Kashmir after August 5, 2019?

However, this dual government did not work out well and in 1935 the British leased out the ‘Gilgit Wazarat’ from the Kashmir Durbar for a period of sixty years, thus ending even a semblance of the presence of the Kashmir Durbar in the region.

The Gilgit Agency was set up on a variety of jurisdictions, and its complicated set up has confused people since its inception. At the core of the Agency was the ‘Gilgit Wazarat’ which was an integral part of the State of Jammu and Kashmir.

However, together with the Wazarat, the Agency was also composed of several ‘tribal areas’ which were associated with the British Agency but did not form part of Kashmir. These were: Chilas, Koh Ghizr, Ishkoman and Yasin. Then there was the jagir of Punial with a hereditary Raja, which was also in direct relations with the British Agency.

Lastly, there were the two small princely states of Hunza and Nagar, which also did not form part of Kashmir State, but had direct relations with the Government of India. All these aforementioned territories then collectively became what was known as the ‘Gilgit Agency.’

In 1947, there were three such leased territories: Gigilt Wazarat had been leased from Kashmir, Berar had been leased from Hyderabad, and Quetta, Nushki and Nasirabad had been leased from Kalat

Thus, the Gilgit Agency was much larger, and different in character than the smaller Gilgit Wazarat which though it formed part of the Agency, and from 1935 had been leased, was technically the territory of the State of Jammu and Kashmir under British administration.

Indian Independence brings up question of states belonging to Gilgit Agency

When the question of the agreement of the princely states to the federal arrangement under the Government of India Act 1935 came up, the status of the several units which constituted the Gilgit Agency arose. The Government of Jammu and Kashmir obviously lay claim to the whole Agency and argued that if it agreed to the federation, not just the Gilgit Wazarat, but the entire Agency including the tribal areas, the Punial Jagir and the states of Hunza and Nagar would follow suit.

In order to bolster its argument, the Kashmir Durbar sent a long memorandum to the Government of India laying claim to all these territories. However, upon examination, the Government of India declared against the Kashmir Durbar. Relaying the official decision, Col. Fraser, the Resident in Kashmir, wrote to the Prime Minister of Kashmir on June 5, 1941:

The Crown Representative regrets that he is unable to agree with all the conclusions reached in the note of the Kashmir Government forwarded with your letter and is pleased to decide as follows:

- Hunza and Nagar: though they are under the suzerainty of the Kashmir State, they are not part of Kashmir but are separate states.

- Chilas, Koh Ghizr, Ishkoman, and Yasin: Though these are under the suzerainty of Kashmir State, they are not part of Kashmir but tribal areas.

Thus it was officially and legally made clear to Kashmir that only the Gilgit Wazarat formed part of the State, and nothing else.

Read more: Article 35A: Who created it, why and how they have turned against it?

Even in terms of the Kashmir ‘suzerainty’ over Hunza and Nagar, the Government of India noted that it was mostly ceremonial. For example, it was recorded in 1881 that ‘Since 1869 Ghazan Khan (of Hunza) has been in receipt of a yearly subsidy of Rs. 2000 from Jammu, nominally in return for allegiance but it is really paid as blackmail to prevent him from making raids into Gilgit territory…owning to the defiant nature of their country, they have successfully resisted every attempt to subdue them by the Kashmir Government.

‘ The Foreign Department of the Government of India further reminded the Kashmir Durbar that their relations with the states of Hunza and Nagar were not independent of the British and that ‘the control…was political and acquired with the concurrence, encouragement or aid of the British Government, and involved external relations with these territories.’ Thus, except for the Gilgit Wazarat, Kashmir Government had no claim on any of the other territories which formed part of the Gilgit Agency.

When the date of the Transfer of Power in August 1947 neared, the British began to end their operations in the princely states as they would all become legally independent countries with the ‘Lapse of Paramountcy’ on August 15, 1947. Thus, it was decided to terminate the leases on territories taken from various princely states so that the states could assume control.

This plan involved that on D-Day, Mathieson would keep control of Chilas and confront the Jammu and Kashmir State forces at Bunji, with the hope that their Muslim contingent would mutiny

In 1947, there were three such leased territories: Gigilt Wazarat had been leased from Kashmir, Berar had been leased from Hyderabad, and Quetta, Nushki and Nasirabad had been leased from Kalat. However, it is very interesting to note that only the Gilgit lease was actually terminated by the Last Viceroy of India Lord Mountbatten, while the decision on both the other leases was left to the successor governments.

Following the decision of the Government of India, the Government of the State of Jammu and Kashmir assumed control in Gilgit Town on August 1, 1947, and Brigadier Ghansara Singh arrived as the new governor.

However, while only the control of the Gilgit Wazarat should have been given to the Kashmir Government, it was assumed that the whole Gilgit Agency was being handed over to Srinagar. F.D. Mainprice, the last British Assistant Political Agent in Gilgit, noted this big mistake and wrote:

‘It was not however realized that Gilgit sub-division was only one-tenth of the Gilgit Agency and that the other nine states and territories which had never been under Kashmir State but always directly under the Central Government, were in quite a different position.’

Read more: India’s Constitutional Deception turns Kashmir into a Volcano

Thus, it seemed that in confusion ensuing from the Transfer of Power, Kashmir State was trying to (or was being helped too?) acquire more territory clandestinely.

Despite the assumption of the Kashmir Durbar of the reigns of government in the Gilgit Agency, it was clear that the whole area, including the Gilgit Wazarat, was pro-Pakistan. The region was almost wholly Muslim, and the people of its different areas did not share ethnicity, language or culture with Kashmir. They had also been practically under British rule for decades and so direct Kashmir Durbar rule came as a shock.

Indomitable Englishman Major William Brown

In August 1947, Major William Brown was the Commandant of the Gilgit Scouts, the only para-military organization in the Agency. Together with Captain Mathieson in Chilas, they were the only two British officers left after the transfer of the Agency to Kashmir hands.

Both these officers were clear that not only were the people unhappy with a return of Kashmir rule, if in case, but Kashmir also acceded to India, they would revolt and join Pakistan. Major Brown noted in his diary that when he went around the Agency for oath-taking ceremonies following the Kashmir takeover, all he was told and sensed was hatred towards the Kashmir Durbar and support for Pakistan.

No wonder then he used the Oxford English Dictionary at one occasion and some old book at another, instead of the Quran, so as to not to force the people to make an allegiance they hated.

India shows the whole Agency now as part of its new union territory of Ladakh, while Pakistan shows the complete Agency as part of Gilgit-Baltistan

Major Brown quoted Muzzaffar, the orderly of the Raja of Punial, who echoed the sentiments of the people of the region:

‘the whole of Gilgit Agency is pro-Pakistan … we could never swear allegiance to Hindustan. Apart from religion, the Gilgit Agency is really a part of the NWFP and is, therefore, a part of Pakistan. If Kashmir remains independent, well and good … .But if the Maharaja through pig-headedness and bad advice, political pressure or attractive remunerations accede to Hindustan, then there will be trouble here!’

Major Brown was clear that if Kashmir joined India, the Agency would erupt in favour of Pakistan. Thus, he decided to throw in his lot with the sentiments of the people of the region and chose to act in case Kashmir acceded to India. He wrote in his diary:

I shuddered at the thought of the havoc which would follow a decision by the ruler of Kashmir to join India. The blame for the widespread destruction of life and property would lie directly on the British government.

I, therefore, felt it was my duty, as the only Britisher left, to follow a course which would prevent this … partisan, traitor, revolutionary, I may have been, but that evening my sentiments dictated that if the Maharaja acceded to India, that I would forego [sic] all allegiance to him and I would not rest content until I had done the utmost in my power to ensure that not only the Gilgit province joined Pakistan, but the whole of Kashmir also. The Rubicon was crossed, and in the future, all my actions were formed by these ideas.

From then onwards it was simply watch and wait for Major Brown and his band of increasingly restless Gilgit Scouts.

Read more: Gilgit-Baltistan: “Bam-e-Dunya” – the roof of the world

While the Kashmir Durbar dithered as to what it would eventually do, Major Brown and Captain Mathieson devised a plan called ‘Datta Khel.’ This plan involved that on D-Day, Mathieson would keep control of Chilas and confront the Jammu and Kashmir State forces at Bunji, with the hope that their Muslim contingent would mutiny.

At the same time, Brown would put the Kashmiri Governor Ghansara Singh under arrest, cut all communication with Srinagar, and cable Pakistan for help. Meanwhile, several members of the scouts like Shah Khan, Subedar Major Babar Khan and Captain Mirza Hassan of the Jammu and Kashmir State forces were also planning a coup.

As the news of the alleged accession of Jammu and Kashmir on October 27, 1947, reached Gilgit, tension immediately arose, and Major Brown decided to spring into action. Thus, on the night between October 31 and November 1, 1947, he sent Subedar Major Babar Khan to arrest Brigadier Ghansara Singh, directed one section of the Scouts to secure the post office, two sections to protect the wireless and one platoon to meet the state forces on their way to Gilgit. He also collected all the Hindus and Sikhs in a refugee camp so that no harm could be done to them.

Captain Mathieson carried out his orders in Chilas and kept a firm hold over the area. With a bloodless coup securing the whole of the Agency, Major Brown then set a telegram on November 1, 1947, to Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan, the Premier of the North-West Frontier Province noting: ‘‘Revolution. Night 31st to 1st in Gilgit Province.

The entire pro-Pakistan populace has overthrown Dogra regime. Owing imminent chaos and bloodshed Scouts and Muslim State Forces running administration temporarily. Request higher authority be approached immediately and reply through wireless. Can carry out meantime. Commandant Scouts.’

The other territories unequivocally threw in their lot with Pakistan in 1947 and their aspirations should be recognized and their people given their just status as citizens of Pakistan and their territories unambiguously shown as part of Pakistan

As the news of the coup in Gilgit spread to the rest of the Agency, the rest of the areas also soon declared their lot with Pakistan. The Raja of Punial, who was thought to be the most pro-Kashmiri of all the governors of the area, sent Major Brown his accession letter written in the vernacular through his son, while both the Mirs of Hunza and Nagar sent in their Instruments of Accession on November 3, 1947, which Major Brown later sent to Peshawar.

Hence, by the time Sardar Alam Khan, the Political Agent appointed by the Government of Pakistan arrived on November 16, 1947, Major Brown had secured the whole of the Gilgit Agency for Pakistan. With no Pakistan involvement, and with only local initiative, and their sentiments for Pakistan, the whole of the Gilgit Agency had declared for Pakistan.

Pakistan New Political Map has an egregious understanding

It has been more than seventy years since the revolt in the Gilgit Wazarat, and the declaration of the people of Chilas, Koh Ghizr, Ishkoman, Yasin, and Punial, and the rulers of states of Hunza and Nagar, to join Pakistan.

Yet not only India, which intelligently follows the claim of the Kashmir Durbar in claiming the whole Gilgit Agency, but even Pakistan seems bent on accepting the erroneous view that the entire Gilgit Agency is a part of the State of Jammu and Kashmir. Hence while both India and Pakistan have competing maps, both perpetuate the false notion that all of the Gilgit Agency formed part of the Kashmir State.

India shows the whole Agency now as part of its new union territory of Ladakh, while Pakistan shows the complete Agency as part of ‘Gilgit-Baltistan.’ Where India has no interest in the correct legal position or cares about the aspiration of the people of the region, it is high time that Pakistan should recognize the correct legal position that Chilas, Koh Ghizr, Ishkoman, Yasin, and Punial, and the states of Hunza and Nagar, were not part of the State of Jammu and Kashmir and should not be yoked together with its territories.

Read more: Pakistan’s strategic brilliance through New Political Map highlighting Kashmir issue

Only the Gilgit Wazarat should be shown as part of Kashmir, and as a ‘Disputed Territory’ under international law. The other territories unequivocally threw in their lot with Pakistan in 1947 and their aspirations should be recognized and their people given their just status as citizens of Pakistan and their territories unambiguously shown as part of Pakistan.

Dr Yaqoob Bangash is a historian at ITU Lahore. He is the author of ‘A Princely Affair: Accession and Integration of the Princely States of Pakistan, 1947-55.’ He can be contacted at Yaqoob.bangash@gmail.com. Tweets@BangashYK