The Economic Survey Report 2017-18 recorded a $12 billion budget deficit from July to March FY2018 and is likely to go beyond 4.9 percent of GDP as opposed to the revised target of 4.2 percent. The tax revenues in the first nine months of the fiscal year amounted to Rs.2627 billion against Rs. 2269 billion during the previous year 2016-17, posing growth of 15.8% on the whole.

The trend vividly suggests that the revised budget deficit target of 4.2% of GDP, approved by the parliament, has entirely become unrealistic as current rate is 4.9% till the end of third quarter. Yet despite increased expenditures, Pakistan remains low on Human Development Indicators and there are apprehensions that Pakistan may go back to the IMF for yet another bailout package.

The critics while evaluating, this situation, point out that only the rising debt and government’s development priorities are being tilted towards high visibility infrastructure projects, yet the low taxation escapes the attention of all stakeholders including the opposition, civil society, economic experts, media, etc. This raises the fundamental question as to “why the low tax-intake in Pakistan is not a hot issue”.

Tax returns and refunds is 560 hours per year. This is the highest in South Asia, where the average time is 331 hours per year.

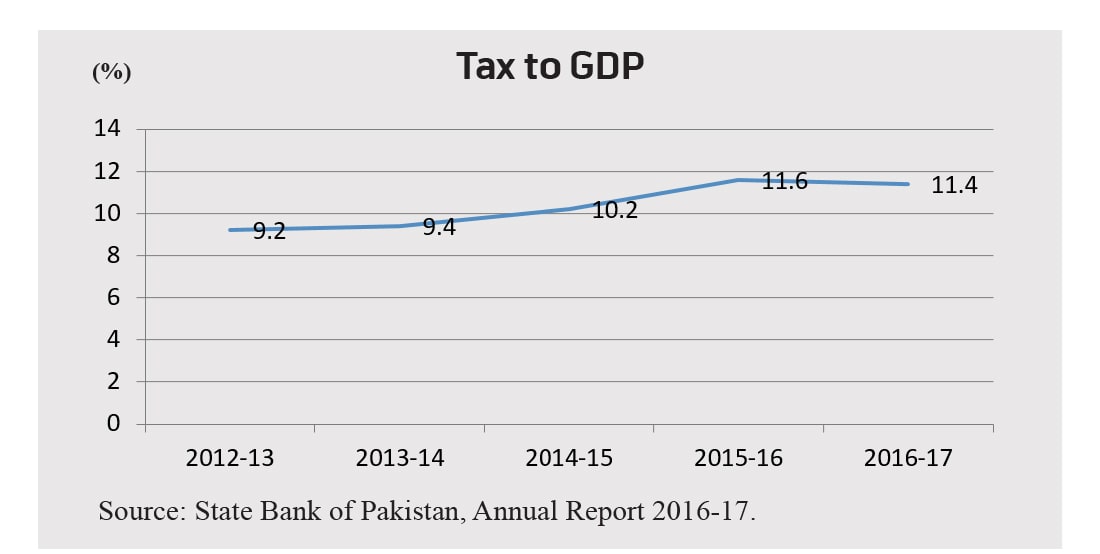

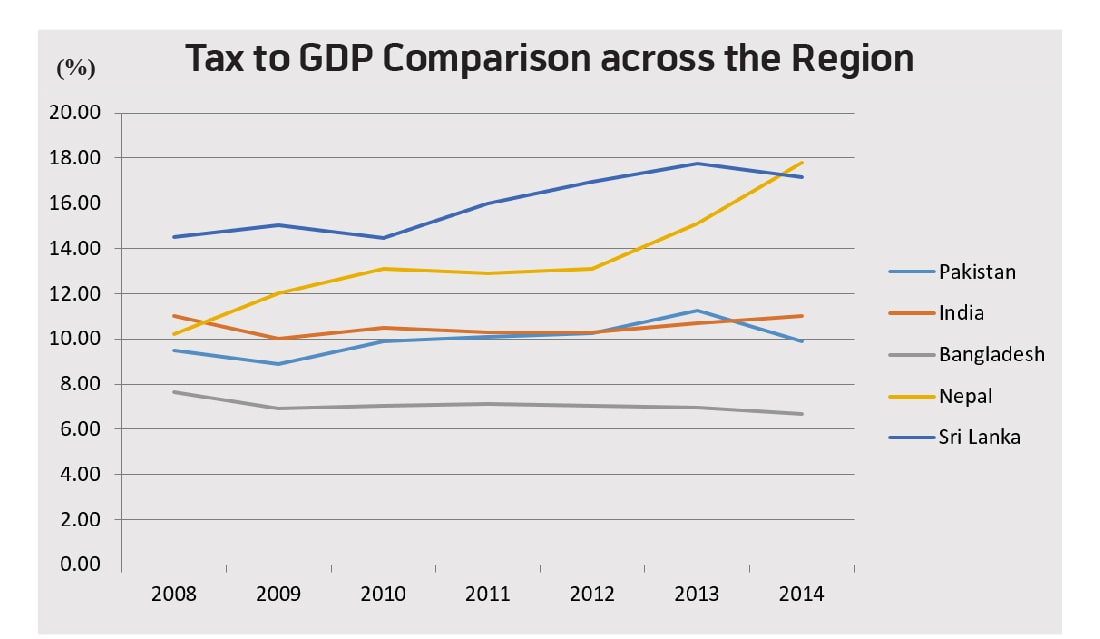

This performance, however, could not be sustained in FY17. “Despite the improvement in recent years, Pakistan’s tax-to-GDP ratio still remains one of the lowest in the region, only better than Bangladesh’s”. It fell far short of the 15.0 percent benchmark envisioned in the National Finance Commission (NFC) Award 2009.

Tax collection in Pakistan is low compared to similar countries, and its tax to GDP ratio has been fairly static over the last decade, as reflected in the chart below: A comparison with other regional countries, as indicated below, reaffirms the position that tax to GDP ratio in Pakistan has not only been static but is lower than other countries in the region.

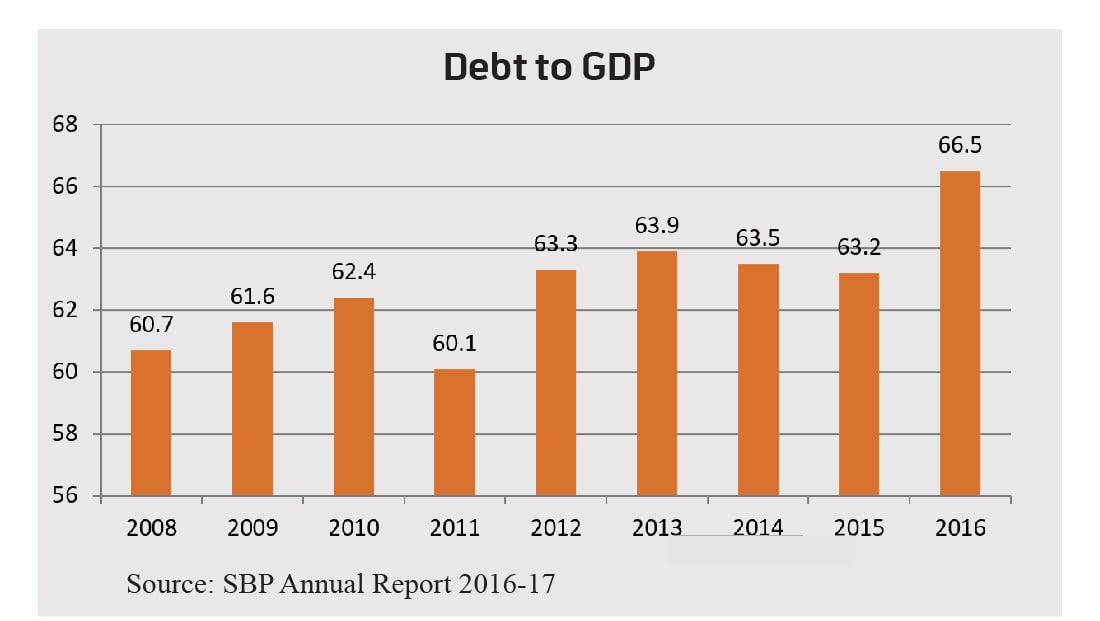

The figures reveal that the Tax to GDP ratio has remained stagnant around 10 percent. Although FBR taxes have increased annually by 18 percent (average) from FY13-FY17, while Debt to GDP ratio has remained between 63-66 percent, the GDP growth rate has remained 4.06 percent over the same period.

Most of the studies attribute low tax collection in Pakistan to factors ranging from a regime of wide-ranging concessions and exemptions and rampant tax evasion to an inefficient and corrupt tax administration. Based on the research, carried out, the reasons can be attributed to proximate causes and structural reasons.

Read more: Health Ministry suggests a further tax slap on tobacco companies

Immediate Causes of Low Tax Collection

An immediate cause of low tax collection in Pakistan is weak tax administration. As in most comparable countries, there are large chunks of the economy that are not documented, for example, the small-scale industry.

For the year 2004-5, estimated tax gap – the difference between estimated potential and actual tax collection – for federal taxes was 69 percent of actual collections. Estimated average tax evasion was about 4 percent of GDP annually over a forty-year time period. Estimates of the informal economy put it at about 50 percent of the GDP.

Reforms were not successful for a number of reasons including, tax policy, frequent changes in political and tax agency leadership, implementation capacity, tax staff resistance to change and generally the government’s weak commitment to reform.

The economic and political elite of the country blatantly flouts tax laws. For example, 60 percent of elected public representatives in national and provincial parliaments do not file any tax returns. From 2004 to 2011, the Tax Administration Reform Project was implemented with assistance from aid donors.

While some progress was made, for example, re-organization of the tax agency and introduction of information technology, which improved databases and some taxpayer services, generally the administrative reforms did not help in improving tax collection.

From 2008 to 2012, the average time spent by taxpayers on preparation and filing tax returns and refunds is 560 hours per year. This is the highest in South Asia, where the average time is 331 hours per year.

Read more: Pakistani exports witness a 24% increase

Federal Government undermines Provincial Taxation System

Some experts attribute this to the tendency of the Federal Government to centralize power. Sub-national taxation in Pakistan is 0.8 percent of its GDP. Pakistan’s tax system is over-centralized; sub-national government taxes contribute about 5 percent to the total tax revenue in Pakistan while the comparable figure for India is 35 percent.

In the case of Pakistan, this is partly because the Federal Government abolished some of the sub-national government taxes such as land revenue and octroi without replacing them with any substantive viable alternatives.

Low rates and non-enforcement of Agriculture Income Tax (AIT) substantially diluted tax revenue from the agriculture sector which constitutes about 25 percent of the GDP. Currently, Punjab government collects only about Rs. 1 billion agriculture income tax; its potential is estimated between Rs. 50-70billion.

Structural Reasons for Low Tax Collections

Experts claim that the intermittent nature of the aid flows to Pakistan helped the government put off the required tax reforms and avoid the political costs of taxation. However, there is little evidence from cross country statistical analysis that aid – including loans and grants – suppresses tax generation in recipient countries.

In the case of Pakistan specifically, the evidence on this issue is mixed and varies for different time periods. It is found that from 1980 to 2000, while loans have had a positive effect on taxation in Pakistan, grants have had a negative effect. Similar work for an earlier period, 1976-95, shows that on the whole foreign assistance enhances taxation efforts.

Read more: Can an increase in remittances boost Pakistan’s economy?

Political (un) willingness to Tax

In theory, the possibility of a premature end to their rule has been cited as one of the reasons why rulers might not be willing to tax the people. Pakistan has oscillated between civil and military rule over the seven decades of its existence. No academic study looks specifically at the connection between political uncertainty and taxation in the case of Pakistan.

One might argue that, on the one hand military regimes were not interested in increasing tax collection, while on the other, elected governments were unwilling to tax due to uncertainty about continuity of their rule. Fear of upsetting powerful interests in absence of a wider political support base might have led military regimes to avoid aggressive taxation.

For example, influential interest groups were the main beneficiaries of tax concessions during General Musharraf’s rule from 1999 to 2008. There is a possibility that due to fears of a premature end to their rule, elected civilian governments in Pakistan do not pursue taxation aggressively.

People’s Willingness to Pay Taxes

There is large literature on tax compliance, examining people’s willingness to pay. Some of the factors that may determine willingness to pay are: attitudes towards authority and the state, expectations of reciprocity by the state, perceptions of other taxpayers’ behavior, experiences with taxpaying and a sense of justice and fairness.

Due to a paucity of evidence, we simply do not know which of these factors shape willingness to pay taxes in Pakistan. We know though, that tax enforcement is selective and often politically motivated; and the politically well connected avoid paying taxes.

This unequal enforcement may foster a feeling of injustice on the part of those who are forced to pay. Further, tax collection mechanisms are not transparent or efficient and public service delivery is poor. All these are possible explanations for people’s resistance towards paying taxes.

Read more: Pakistan’s World of Cement: Opportunities and Challenges

Resistance by Powerful Groups

Resistance by the elites interest groups can take a number of forms, including, influencing tax policy and ensuring that tax collection is not enforced. Influence on tax policies in Pakistan is reflected in the arbitrary system of awarding exemptions and concessions in various taxes. Tax expenditures have been estimated at about a fourth of total taxes collected by the Federal Government.

Selective enforcement of tax collection by the government and tax evasion by the political and economic elite is a major factor for low tax collection in Pakistan. Government’s inability to effectively implement agricultural income tax is a case in point. A majority of politicians represent rural constituencies themselves have substantial agricultural landholdings and have avoided the tax net.

Since the influential are not interested in the use of public services and the poor, who rely on them, do not have the voice to readjust the numbers on the expenditure side of the equation, there is little pressure on the government to make efforts on the revenue side of the equation.

The effect of low taxation is that there is less money available with the government to spend, which results in the allocation of the budget on various heads depending upon the political expediency. Since the taxation has remained fairly static over the past few years, the consequence is that it would be difficult for the government to vary the resources, allocated to development and non-development activities, significantly.

Thus, the concept of low-level fiscal equilibrium becomes relevant for Pakistan. The term is used to signify a situation in which governments neither make the kinds of efforts one might expect to obtain more revenues for themselves nor appear to be under strong pressures to spend more money on public goods. The Revenue and Expenditure represent two sides of an equation, which can be represented as below:

T + NT + D = DS + Defence + PSDP + (Salaries & Pension) + Grants + PSDE

Low-level fiscal equilibrium occurs when the revenue side of the equation is low and when government finds it difficult to increase taxation, the consequence should either be (a) reduction on the expenditure side in any head to balance the Revenue side; or (b) borrowing, in the shape of debt, to meet desired levels of expenditure, under each head on the expenditure side.

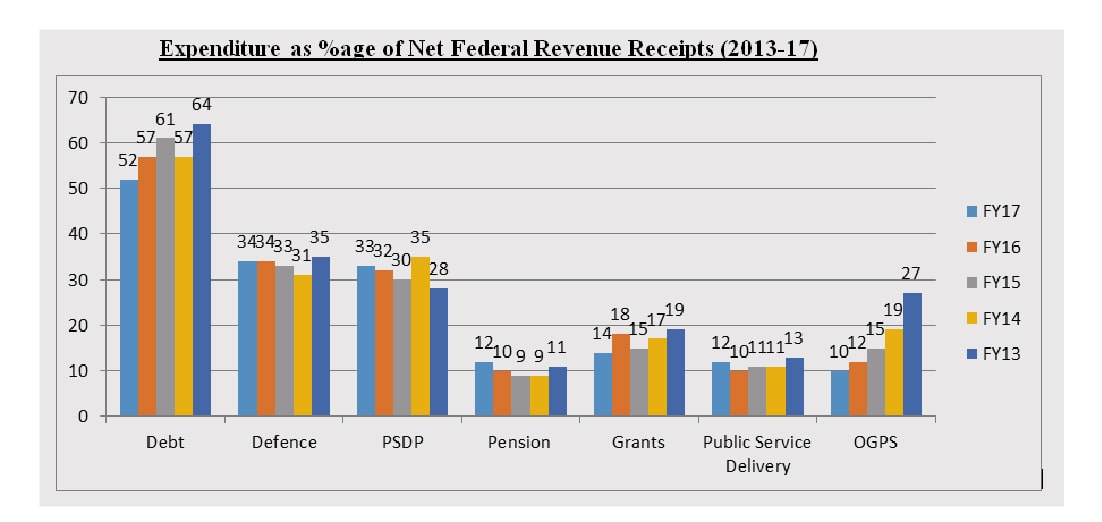

The figures, over the last five years, reflecting the amounts spent on major heads of expenditure (as a percentage of Net Receipts), reveal the following position. The below figure reveals an interesting picture. The expenditure on various heads has remained fairly static over the last five years. While debt servicing (DS) and defense related expenditure consume a major chunk of the available resources, the remaining have to be apportioned amongst the development and non-development expenditure.

As seen, the development (PSDP) has remained consistently around 30-35% of the net receipts, the remaining resources are distributed among pension, salaries, grants, and expenditure on public service delivery. While the government is constrained to make expenditure under heads like debt servicing, defense, pension/salaries, etc. the cushion available to the government is between the capital expenditure (PSDP) and public service delivery expense (PSDE).

Read more: Amid rising macroeconomic instability, IMF cuts down Pakistan economic growth to…

Expenditure Rising Despite Low Taxes

Article 84 of the Constitution provides that if a need has arisen for expenditure upon some new service not included in the Annual Budget Statement for that year; or that any money has been spent on any service during a financial year in excess of the amount granted for that service for that year; the Federal Government shall have the power to authorize expenditure from the Federal Consolidated Fund.

This gives unbridled power to the Executive to spend as per its (political) priorities with virtually no check of the legislature. As evidence suggests the variation, between the budgeted amount and actual expenditure, has ranged from 12% to 90% during the 2005-06 to 2011-12 period.

This provision provides enough flexibility to the executive to determine its priorities and spend according to its political needs. It is usually the expenditure on Public Service Delivery which takes the brunt while the PSDP gets a boost. Further, the limits imposed by the Fiscal Responsibility and Debt Limitation Act 2005, on debt to GDP ratio and fiscal deficit have been avoided by delaying its implementation through amendments incorporated in the guise of Finance Bill(s).

Civil Servants not Interested in Development Expenditure

Despite a large wage bill, the government always manages to pay its employees, even during periods when it is relatively short of money. In the absence of any service delivery targets public servants are largely satisfied with allocations for recurrent expenditures – employee-related expenditures and PSDE – provided they get paid and maintain their privileges.

The government is bound to increase salaries and pensions every year since the public service. Second, the number of government employees rises continuously, as new projects are completed and have to be supported by staff. Politicians are interested in creating new jobs, especially non-skilled jobs, where politicians normally recruit their supporters and clients.

Third, the annual pension bill of the government is growing rapidly. Thus there is little pressure to deliver public services and the government can cut PSDE without any immediate political risk.

In absence of political pressure to deliver services and because the government so far has been able to pay salaries even during periods of resource shortages, public servants have little reason to pressure the government to increase its income, through increased taxes.

The analysis has shown that while it has been difficult to increase the taxes due to proximate and structural reasons, the politicians and public servants find it expedient to maintain certain levels of PSDP and salaries/pensions respectively, after making payments related to defence and debt servicing, resulting in reduction in PSDE, the expense on the common man.

However, the consumer of PSDE, being politically non-influential and unable to exert pressure on the government, gets reduced expenditure and thus poor public service provisioning. Since the influential are not interested in the use of public services and the poor, who rely on them, do not have the voice to readjust the numbers on the expenditure side of the equation, there is little pressure on the government to make efforts on the revenue side of the equation.

Read more: CJP questions the illegal high taxes on mobile users

Further, the executive has unbridled powers to re-appropriate public funds, amongst various heads, and is under no pressure from the legislature to remain within the budget approved by the legislature. This further exaggerates the fiscal deficit, hence the need for borrowing to make up the deficit.

It is the excessive borrowing and use of development funds, on projects of high visibility, which come under scrutiny from the opposition, civil society and media. Since the needs of influential (Politicians, Military, etc) vis-à-vis their expenditure priorities are met by increased levels of debt and freedom to prioritize the expenditure preference, the issue of low taxation, the revenue side of the equation, is never an agenda to be discussed amongst the influential and is unable to find its way in the public debate.

Recommendations

In order to handle the issue of low taxation, keeping in view the previous reform efforts on the revenue side did not achieve the desired results, there is a need to focus on the expenditure side of the equation as well. In view of the above, the following is suggested:

There is a need to introduce political and social accountability of public spending to bring the expenditure in the realm of public debate. We have seen that parliamentary oversight, in this regard, is compromised by Article 84. Thus, it is suggested that Article 84 may be amended so that any expenditure beyond the budget, approved by the Parliament, shall require the prior approval of the same institution.

The limits set by the Fiscal Responsibility and Debt Limitation Act 2005, vis-a-vis debt to GDP ratio and fiscal deficit, need to be respected by the Government. Any amendment, through finance Bill(s), delaying the timelines for implementation of the limits shall require a 2/3rd majority of the Parliament.

Imposition of limits on the development expenditure, on similar lines as done by NEC limiting the development budget to Rs. 152 Billion, shall make more money available for the expenditure on public service delivery. Similarly, large infrastructure projects need to be financed through the PPP mode instead of PSDP.

The absence of service delivery targets put no pressure on the politicians and civil servants to provide adequate quality services to those relying on public services. The introduction of service delivery targets, and linking the budget with achievement, is likely not only to put pressure on the service providers to deliver but will also improve service quality and delivery.

Read more: The Government of Pakistan wants to put taxes on Facebook, Google

At the moment, the policy formulator and policy implementer are combined (literally) in one office. Thus, the policy formulator needs to be separated from the provider of service delivery in order to have an effective evaluation of the policy and independent policy formulation. The office of Secretary, Revenue Division shall not only be strengthened but needs to be separated from Chairman FBR.

Complex tax filing procedures and paperwork need to be simplified. Once, the separation of policy from service delivery takes place, complex procedures and paperwork shall be simplified.

Incentivizing the tax collectors, by providing them one extra salary, has not worked in the past. Incentivizing them with some proportion of collected revenue has its own perils and not incentivizing them shall result in similar results. It is therefore proposed that their KPIs should be linked with the increased number of filers in order to broaden the tax base.

This will also impact their service delivery as the potential filers would not be subjected to complex paperwork/ questions and corrupt practices. Incentives for tax filers shall also be introduced on the following lines:

- Preference in contracts for suppliers to government departments;

- Guaranteed refund within the stipulated time;

- Access to a bank loan up to a certain limit;

- Partial or full exemption from withholding taxes;

- Preferential treatment in obtaining access to public

- Services such as electricity or gas supply.

Saud Bin Ahsen is Public Administration & Economics graduate from Punjab University & GCU Lahore and associated with a Public Policy Think Tank Institute. He is interested in Comparative Public Administration, Post-Colonial Literature, and South Asian Politics.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Global Village Space.